China Uses One-Third of World’s Soybeans

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Mark Stebnicki, North Carolina Farm Bureau

For the 2018/19 marketing year, Chinese soybean utilization for domestic crushing and exports is projected at 4.2 billion bushels. Global soybean production for the marketing year is projected at 13.2 billion bushels, meaning China is expected to use the equivalent of nearly one-third of every acre of soybeans harvested in the world. Based on average soybean yields of 41 to 48 bushels per acre, China’s soybean utilization represents 87 to 102 million acres worldwide – equivalent to or greater than total U.S. soybean acreage.

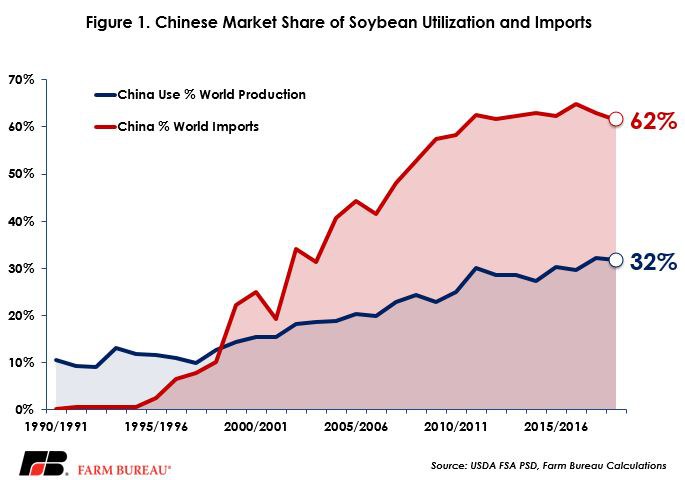

Since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, its role in the soybean complex has expanded considerably. During the 2001/02 marketing year, China used 15 percent of global soybean production and Chinese imports represented 19 percent of world soybean trade. Now, in 2018, not only does China use one-third of every acre, but its imports represent 62 percent of global soybean trade. For the 2018/19 marketing year, USDA projects Chinese soybean imports at 3.5 billion bushels, and global soybean trade at 5.7 billion to 5.8 billion bushels. Chinese soybean imports are up 815 percent since joining the WTO. Figure 1 highlights Chinese market share in world soybean utilization and trade.

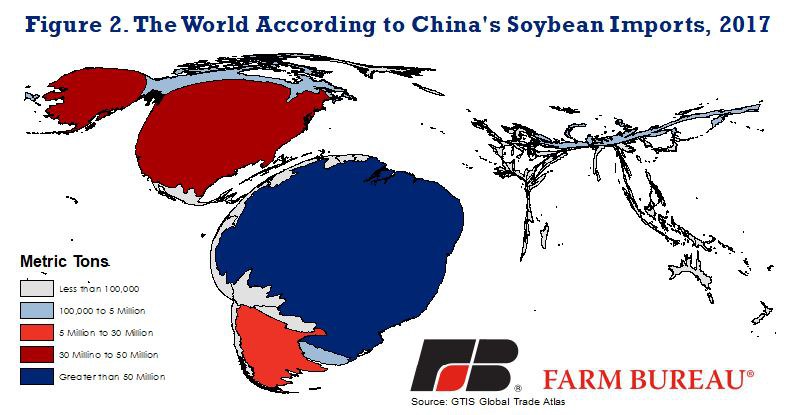

With China using one-third of global soybean production, a logical question is: where are the soybeans coming from? During the 2017 calendar year, China imported 3.6 billion bushels of soybeans from 16 countries. Figure 2 shows an area cartogram map that bases the map geometry on the number of soybeans exported to China in 2017, i.e., the world according to Chinese soybean imports. As evidenced in Figure 2, the largest soybean supplier to China was Brazil at 54 million metric tons, or 1.98 billion bushels, followed by the United States at 32 million metric tons, or 1.2 billion bushels. Combined, 89 percent of China’s soybean imports in 2017 came from Brazil and the U.S.

Could China Go Elsewhere?

While China has predominately relied on Brazil and the U.S. for soybean purchases, that does not have to be the case, and currently, China is reducing its dependence on U.S. soy. Recent Market Intel articles have reviewed cancelled U.S. shipments to China: Lost Soybean Sales to China Continue to Climb and Drop in Soybean Exports Coincides with Steely Announcements on Trade.

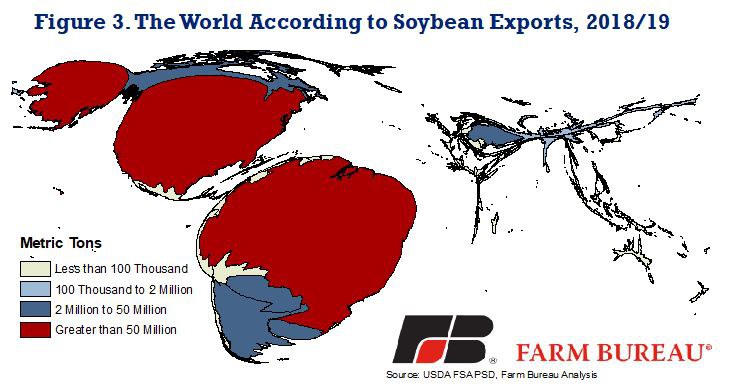

To meet the growing demand for soybeans, several South American countries have rapidly expanded soybean production over the last decade. Soybean production in Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay has increased by 75 percent, 52 percent and 51 percent, respectively. Similarly, exports from these three countries have increased 162 percent for Brazil, 27 percent for Paraguay and 48 percent for Uruguay. Combined, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina are projected to export 3.4 billion bushels of soybeans in 2018/19 – roughly equal to Chinese import demand. So yes, China can, and more importantly is, sourcing soybeans from other suppliers.

Is it enough to totally displace the U.S.? Currently, no. A majority of the soybean production and exports are in North and South America. Ninety-seven percent of all soybean exports will be from Brazil, U.S., Argentina, Paraguay, Canada and Uruguay. Figure 3 highlights the world according to soybean exports.

The potential exists for lost U.S. sales to China to find a source elsewhere in the global market. As a result, USDA has only slightly reduced U.S. soybean exports for the new crop. For the 2018/19 marketing year, USDA projects U.S. soybean exports to fall to 2.04 billion bushels, down 6 percent from 2016/17 and down 2 percent from 2017/18 (WASDE Weighs in on Soybean Tariffs). Importantly, it is only 250 million bushels below the June World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates.

In the long-run, however, this trade dispute could lead to additional investment in planted acreage and transportation capacity in other parts of the world. Such a scenario would erode U.S. market share in the Chinese market and reduce the profitability of U.S. farmers.