Crops Currently in Poor Condition, But We Still Have Time

photo credit: Tennessee Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

John Newton, Ph.D.

Vice President of Public Policy and Economic Analysis

Implications

Each week USDA’s Crop Progress report updates crop condition ratings for major field crops. These weekly indicators of crop health are closely monitored for corn, soybeans and wheat, and drive price expectations throughout the growing season. At this time of year, poor crop conditions may lead to price rallies while more favorable growing conditions may lead to lower new-crop futures prices. These weather-driven price rallies present opportunities for growers to potentially lock higher returns per acre for a portion of their expected crop. However, based on historical crop yield data, it is too early to use crop conditions alone as an indicator of crop size.

Current Crop Conditions

The June 5, 2017, Crop Progress report indicated that 6 percent of the corn crop was in poor to very poor condition – higher than prior year levels of 4 percent, but 1 percentage point lower than last week’s estimate. Condition ratings for corn also identified 68 percent of the corn crop in good-to-excellent condition--7 percentage points below the prior year but 3 percentage points above last week. The corn crop is clearly improving across parts of the U.S. following a poor start to the growing season. Early season concerns have put a large number of acres at risk, however, and many in the trade are anticipating a pullback on U.S. corn production in 2017 (reduced acreage and/or yields).

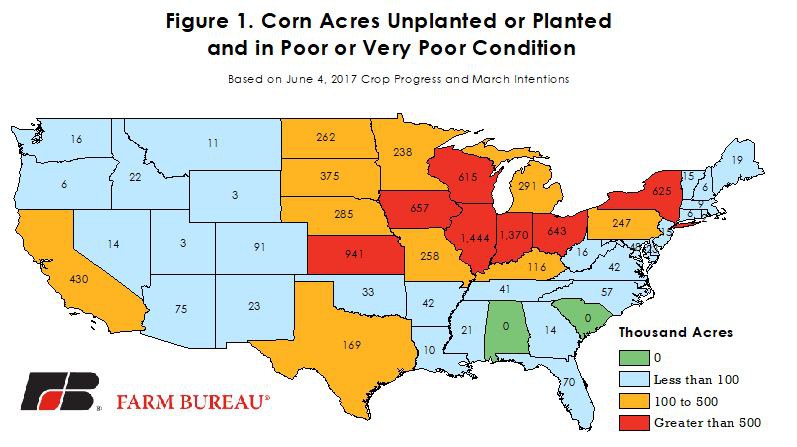

Based on March planting intentions, the percent of the corn crop in poor or very poor conditions is equivalent to 5.1 million acres. Additionally, 4.6 million acres of corn remain unplanted, which means together there are 9.7 million corn acres either unplanted or planted and in poor or very poor condition, Figure 1.

As identified in Figure 1, the Eastern Corn Belt is experiencing the most severe effects from weather conditions so far this planting and growing season. These states had above average rainfall paired with cooler than average temperatures this planting season. Conditions like these stall planting and make it difficult for crops to grow because of possible negative effects on seed germination, soil nutrient content and root structure.

Areas with acres in poor or very poor condition possibly have been replanted or are being allocated to a different crop in the coming weeks. For example, unplanted corn acres may be planted to soybeans at this point because soybeans require a shorter growing season than corn and are typically planted later regardless of weather conditions. Final planting dates for soybeans range from early to late June depending on location.

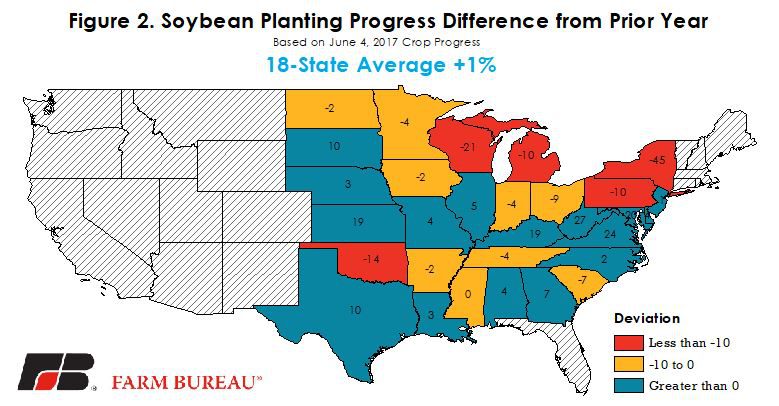

Overall, soybean planting is on track with the previous year at 83 percent planted, and only slightly above the past five-year average of 79 percent. In the western Midwest, soybean planting has been largely unaffected by the weather, and many of these states are well ahead of average. The states surrounding the Great Lakes, however, are lagging due to recent excessive rainfall, Figure 2. The June 12, 2017, Crop Progress report will feature the first soybean condition ratings of the 2017 growing season.

Do Conditions Matter Yet?

An important question when considering these early-season crop conditions is do they even matter yet? The answer is … not really. The 2016 crop saw similar weather concerns before revealing record-high soybean and corn crops. There remains plenty of time in the growing season for the crop to improve. As evidence, the USDA’s weather-adjusted trend yield model for corn and soybeans monitors a combination of June through August precipitation and temperatures as conditioning information. For corn, mid-May planting progress is also statistically significant. What’s not statistically significant, according to USDA, are weather conditions in late-April or May.

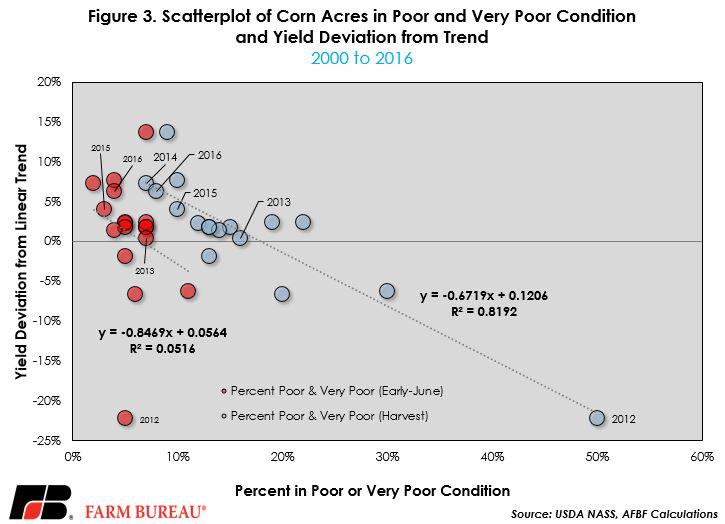

As additional evidence, and using data from 2000 to 2016, a linear regression of early-June corn crop conditions and the yield deviation from trend shows that the percent in poor or very poor condition explains only 5 percent of the yield variability, Figure 3. Similarly, the percent of the corn crop in good-to-excellent condition in early June explains 2 percent of the yield deviation from trend.

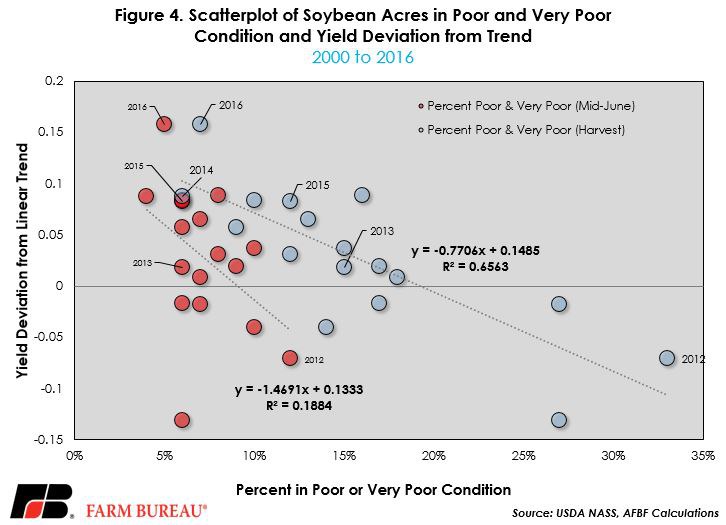

For soybeans, a linear regression of early-June soybean acres in poor or very poor condition explains 19 percent of the yield deviation from 2000 to 2016, Figure 4. While this is an improvement over the corn ratings, it still has low explanatory power.

Conditions Will Matter

As mentioned earlier adverse weather can be detrimental to soil and plant health and can contribute to lower crop yields. June through August weather conditions play a significant role in explaining crop yields.

Corn and soybeans need warm growing conditions, but not too warm. Rain makes grain, but too much rain can damage crop yields, as does too little rain. Information on rainfall and temperature will become available in the coming weeks, as will updated information on crop conditions. By harvest time the crop conditions will certainly matter. A large percentage of the crop in poor or very poor condition would most likely be a result of adverse weather and would be expected to negatively impact crop yields.

As identified in Figures 2 and 3, harvest-time crop conditions have significantly more explanatory power for determining yield deviations from trend. A linear regression of harvest corn crop conditions and the yield deviation shows that the percent of acres in poor or very poor condition explains 82 percent of the yield variability--compared to 5 percent in early June. For soybeans, harvest-time crop conditions show that the percent of acres in poor or very poor condition explain 66 percent of the yield variability--compared to 2 percent in early June.

At this point in the growing season, the empirical data and USDA’s weather-adjusted trend yield model suggest it is too early to use crop conditions as a significant measure of potential yield variability. While the explanatory power is low at this point, the market may react to unanticipated declines in crop conditions or other supply and demand indicators - creating marketing opportunities at higher prices to reduce downside price risk.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL