Low Mississippi River Water Levels Threaten Grain Shipments, Spur Record Rates

TOPICS

Transportation

photo credit: Getty

Daniel Munch

Economist

With harvest well under way across the country, one method of transportation that has been largely spared from recent supply chain snarls has run aground, literally. Limited rains across the Midwest and South have dropped the water level on the Mississippi River, a major thoroughfare for moving grain, to levels too shallow for many barges to effectively navigate. Today we dive into the available statistics to understand the possible wide-reaching impacts of continued barge slowdowns.

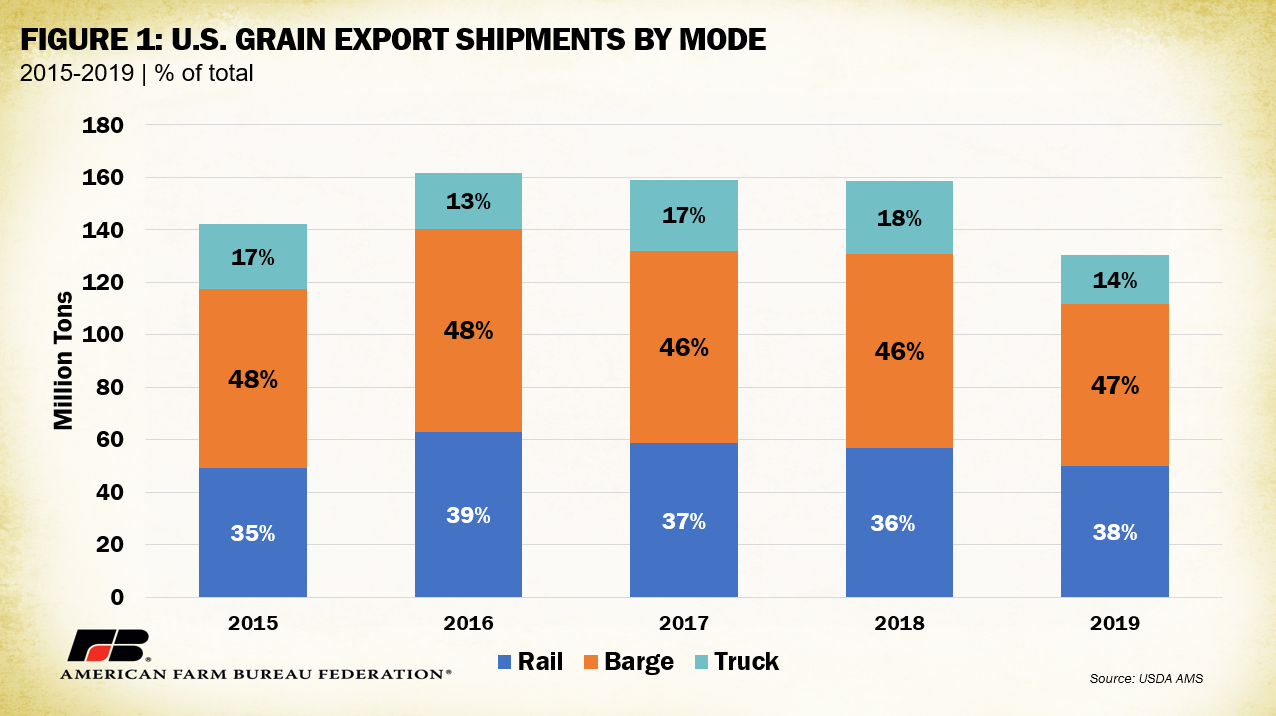

Waterborne transportation accounts for about 7% of all U.S. freight movement annually. When broken down more specifically to grain movements, this share increases. According to USDA’s modal share analysis of grain transportation, between 2015 and 2019 (the latest available data points) barges consistently moved around 13% of all U.S. bulk grain and 47% of all grain destined to export markets. Figure 1 displays the export volume and share of grain by transportation mode between 2015 and 2019. Barge transportation has moved an average of 70 million tons of grains destined for export (47% of total), rail has moved an average of 55 million tons (37% of total) and truck about 24 million tons (16% of total). Given the large role of foreign markets in providing revenue to U.S. farm businesses, even small disruptions to barge efficiency could have rippling effects on producer income.

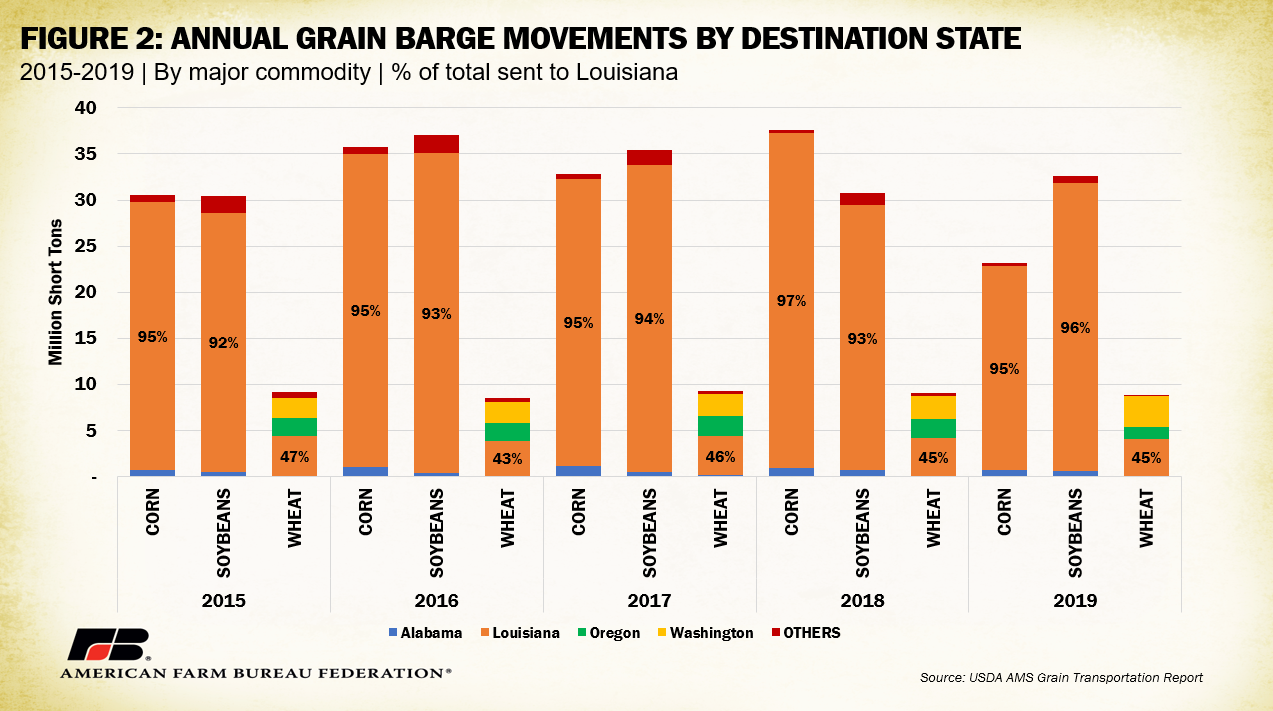

With barge an essential transportation option for producers to move product, it is important to understand the significance of the Mississippi River compared to other domestic inland waterways. USDA tracks volume of corn, soybeans and wheat moved by barge by destination state. A destination state listing of Louisiana captures a large quantity of grain moved through the Mississippi River system as New Orleans remains a primary grain export and distribution point in the United States. Between 2015 and 2019, 95% of corn, 94% of soybeans and 45% of wheat moved by barge traveled through the Mississippi River system to Louisiana. This corresponds to an average annual volume of 32 million tons of corn, 33 million tons of soybeans and 9 million tons of wheat traveling to Louisiana. The only other destination states with a significant portion of barge grain movements are Oregon and Washington, which receive between 15% and 40%, respectively, of wheat deliveries via inland waterway (such as the Columbia River). The vast network of locks and dams, prevalence of grain elevators and vessel service facilities, and the simple geography of the Mississippi/Missouri river system running through production-heavy heartland states make utilizing alternative waterways unrealistic.

According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the stage, or height of the river’s surface relative to standard sea level, for the Mississippi at New Orleans is 2.53 feet as of Oct. 10. This is 48% lower than the prior three-year average of 4.95 feet. In some areas further upriver, levels have dropped to their lowest since 1988, when near-zero stages created far-reaching disruptions to barge movement. Near Stack Island, Mississippi, for instance, after several boat groundings, 111 boats were left waiting with over 1,750 barges southbound, and 74 boats were left waiting with over 1,138 barges northbound for a total of 185 boats with 2,888 barges waiting for dredging or water levels to rise as of Oct. 10. By afternoon, the Coast Guard had made some progress in reducing barge congestion via dredging, though it is unclear how long these fixes will hold if dry conditions persist. More generally, over the past five weeks, 2,466 barges have been unloaded in New Orleans, down 25% from the five-year average.

The industry has responded to low water levels by reducing draft allowances, or the depth a barge may sink into the water, which has resulted in a 20-27% reduction to the volume of goods moved (the greater the volume on a barge the deeper it sinks). Beyond draft allowances, the industry had also agreed to a reduction in tow size, or the number of barges a single boat can tow, to 25 – a 17-38% reduction. Combined, this means more barges will be needed to move the same quantity of products and more boats will be needed to move smaller groups of barges, pressuring capacity and slowing downstream user efficiency. Pressured capacity in barges and boats increases competition for transportation, pushing up costs for shippers looking to get product moved.

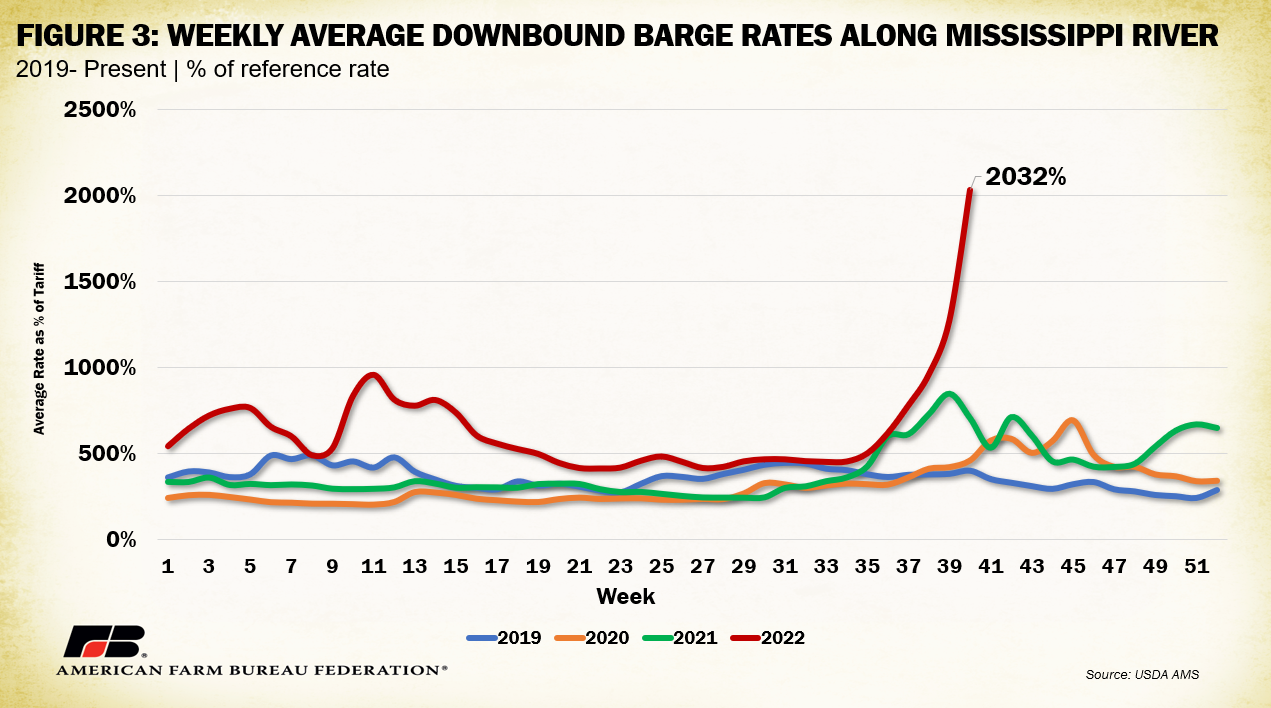

USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service tracks weekly barge rates for downbound freight originating from seven locations along the Mississippi River system. The seven locations are: Twin Cities, a stretch along the Upper Mississippi; Mid-Mississippi, a stretch between eastern Iowa and western Illinois; Illinois River, along the lower portion of the Illinois River; St. Louis; Cincinnati, along the middle third of the Ohio River; Lower Ohio, approximately the final third of the Ohio River; and Cairo-Memphis, from Cairo, Illinois, to Memphis, Tennessee. The U.S. inland waterway system utilizes a percent-of-tariff system to establish barge freight rates. The tariffs were originally from the Bulk Grain and Grain Products Freight Tariff No. 7, which were issued by the Waterways Freight Bureau (WFB) of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). In 1976, the United States Department of Justice entered into an agreement with the ICC which deregulated barge rates and made Tariff No. 7 no longer applicable. Today, the WFB no longer exists, and the ICC has become the Surface Transportation Board, which does not have jurisdiction over barge rates on inland waterways. However, the barge industry continues to use the tariffs as benchmarks for rate units. Each city on the river has its own benchmark, with the northernmost cities having the highest benchmarks. They are as follows: Twin Cities = $6.19/ton; Mid-Mississippi = $5.32/ton; St. Louis = $3.99/ton; Illinois = $4.64/ton; Cincinnati = $4.69/ton; Lower Ohio = $4.46/ton; and Cairo-Memphis = $3.14/ton.

Figure 3 displays weekly average downbound barge rates for the seven locations since 2019. The rate represents the percent increase over the reference benchmark. During the week of Oct. 4, average barge tariffs reached record levels at over 2,000% of their underlying benchmark (2,032%), 50% higher than last year and 131% higher than the previous three-year average. One dollar value example: the cost per ton to ship from St. Louis to the Gulf was $90.45/ton, up 218% from last year and up 379% from the three-year average. The backlog in barge movements, reductions in volume requirements, and inability to find alternative transportation options have pushed barge costs for shippers to new heights.

Unfortunately, water depth is not the only obstacle barge transportation will face over the next few months. To accommodate the removal of a gas pipeline, the Lower Mississippi River (LMR) will implement a series of closures and restrictions in October and November. The latest USDA Grain Transportation Report states that south of mile marker 189.5 (roughly 80 miles north of New Orleans), the LMR will be closed to all southbound traffic from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., Oct. 17-22, Oct. 26-31, and Nov. 4-8. Southbound traffic may need to proceed more slowly than usual on Oct. 4-6, Oct. 23-25, and Nov. 1-3. These restrictions will only make it more difficult for goods to be efficiently delivered.

Conclusion

Agricultural producers have dealt with a wide range of supply chain shortfalls since the onset of COVID-19. Railway and trucking have encountered an array of service issues often linked to labor and equipment capacity constraints. Largely unaffected until now, barges have remained a relatively inexpensive and reliable way to move product across the country, and especially to export ports. Studies have shown barges can provide transportation at a tenth of the cost of rail and a sixteenth of the cost of trucking when available. The new limitations on this cost-effective and efficient transportation mode because of dangerously low water levels in the Mississippi River is especially problematic during the height of harvest season, when farmers are looking to move grain to storage facilities. Without relief, many producers will scramble to find places to store their goods or face exorbitant wait times and costs to acquire transportation.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL