NAFTA: Feed Grains

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Senior Economist

Background

Feed grains, used predominantly to feed livestock, commonly include corn, grain sorghum, barley and oats. Today, corn and grain sorghum span the majority of feed grain harvested acres, accounting for approximately 90 percent and 6 percent, respectively, of harvested feed grain acreage in the 2016-17 marketing year. Barley accounts for 3 percent and was covered in the June 30 article: NAFTA: No U.S. Barley, No Mexican Beer. Oats, which accounted for 25 – 35 percent of harvested feed grain acres through as late as the mid-1950s, accounts for only about 1 percent of planted acres today. This discussion of the importance of NAFTA to feed grains will focus on corn and grain sorghum.

In recent years, Mexico has been the top export destination for U.S. corn, with Japan serving as a close second. Which market is the top destination tends to be a function of timing, exportable supplies from competing producing nations and exchanges rates. Whether Mexico ranks number one or number two in a given year, it is a market of critical importance for U.S. corn. Since NAFTA came into effect in 1994, the U.S. has exported more than 163 million metric tons of U.S. corn, valued at nearly $30 billion, to Mexico. Exports have grown more than 7,100 percent by value and more than 4,700 percent by volume since 1993.

Mexico is also particularly important to the grain sorghum market. For many years Mexico had, far and away, been the top export destination for U.S. grain sorghum, regularly purchasing more than 50 percent of exported U.S. sorghum. That situation changed in 2014, once China began aggressively purchasing grain sorghum. Since that time, Mexico has continued to be a steady buyer, when exportable supplies have been available, but at a significantly lower level. Mexico’s average purchases of U.S. sorghum over the three year period before China entered the market were $457 million. Since China began buying grain sorghum, Mexico’s annual purchases have averaged $89 million, though purchases are trending upward. In previous years, Mexico has bought lower volumes of grain sorghum from Argentina, though Mexico’s import data since 2014, shows that Mexico hasn’t been making grain sorghum purchases from other markets, rather Mexican importers have simply made fewer grain sorghum purchases.

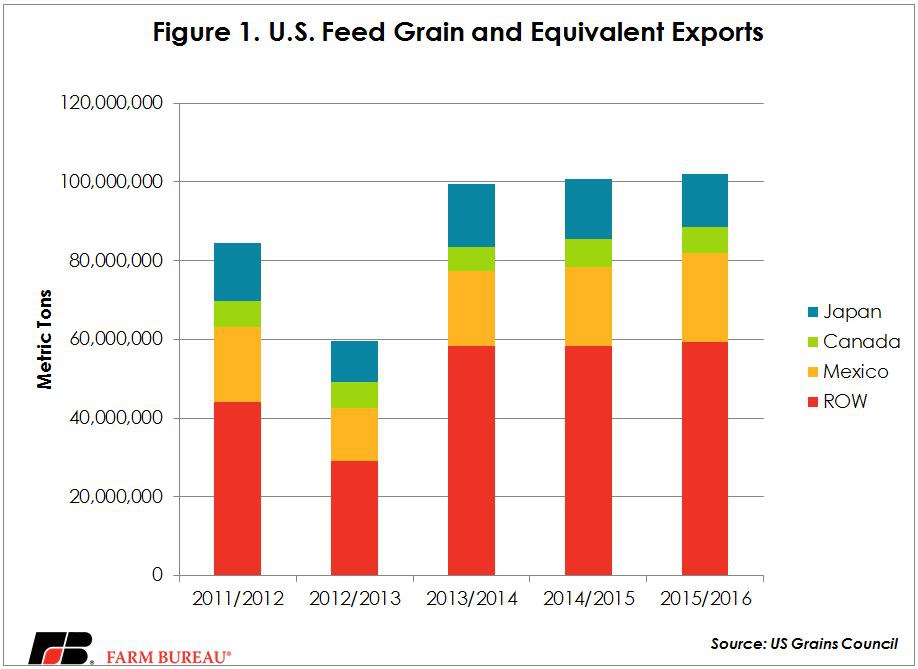

To this point, the export figures quoted have been limited to exports of raw grain, but to stop there would underestimate the total impact that our NAFTA partners have on U.S. feed grains. The U.S. Grains Council has put together a wonderful resource that captures U.S. feed grain exports in all forms. Their website states, “Grains In All Forms calculator converts volumes of exported U.S. corn, sorghum, barley, distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS), corn gluten feed (CGF), corn gluten meal (CGM), ethanol and meat products into corn equivalents, which offers a different and more holistic view of the amount of feed grains produced by U.S. farmers and consumed by overseas customers.” To highlight the importance of including value added corn exports, consider this: In the 2015/2016 marketing year, the U.S. exported a combined $2.6 billion in corn, grain sorghum and barley to Mexico. When all of the value added corn equivalents are factored in, however, that number rises to $6.6 billion. The story with Canada is perhaps even more dramatic. The 2016 export value of corn, barley and grain sorghum was almost $175 million, but when value added products are brought into the equation the total value jumps to $3.2 billion.

Utilizing data from the U.S. Grains Council’s Grains in All Forms calculator, figure 1 highlights the steady purchases of Canada and Mexico, as well as Japan.

The Future is Now

Geographically close with strong transportation options (rail, truck and ship) and strong livestock industries, Mexico and Canada are natural markets for U.S. feed grains and value added products that rely upon U.S. feed grains. We have grown to rely on Mexico and Canada as reliable purchasers of 25-35 percent of U.S. feed grain exports (direct grain plus equivalent). However, our NAFTA partners, Mexico in particular, have been a bit rattled by talks of NAFTA renegotiation and have begun actively looking elsewhere for their corn supplies. Mexican politicians have publicized trips to Argentina and Brazil in search of exportable corn inventory. Some of this talk is political, intended to get the attention of the U.S. Some is likely motivated by actual concerns about disruption to supply that could occur if NATA re-negotiations don’t go well.

This has left many to wonder out loud, "Could our NAFTA partners source enough corn outside of the U.S.? And if Mexico in particular were to go away as a major customer, who would pick up the slack?"

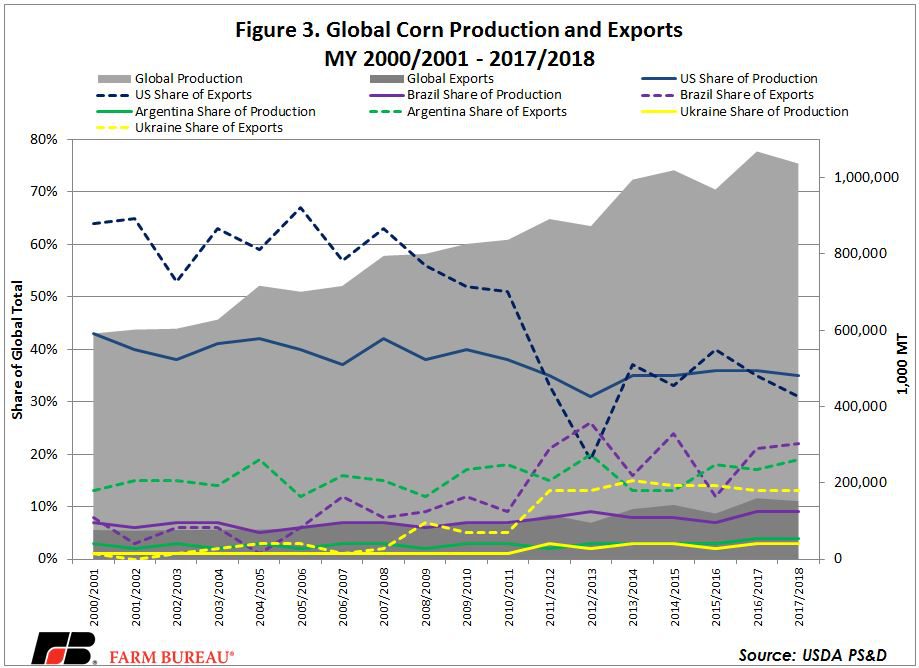

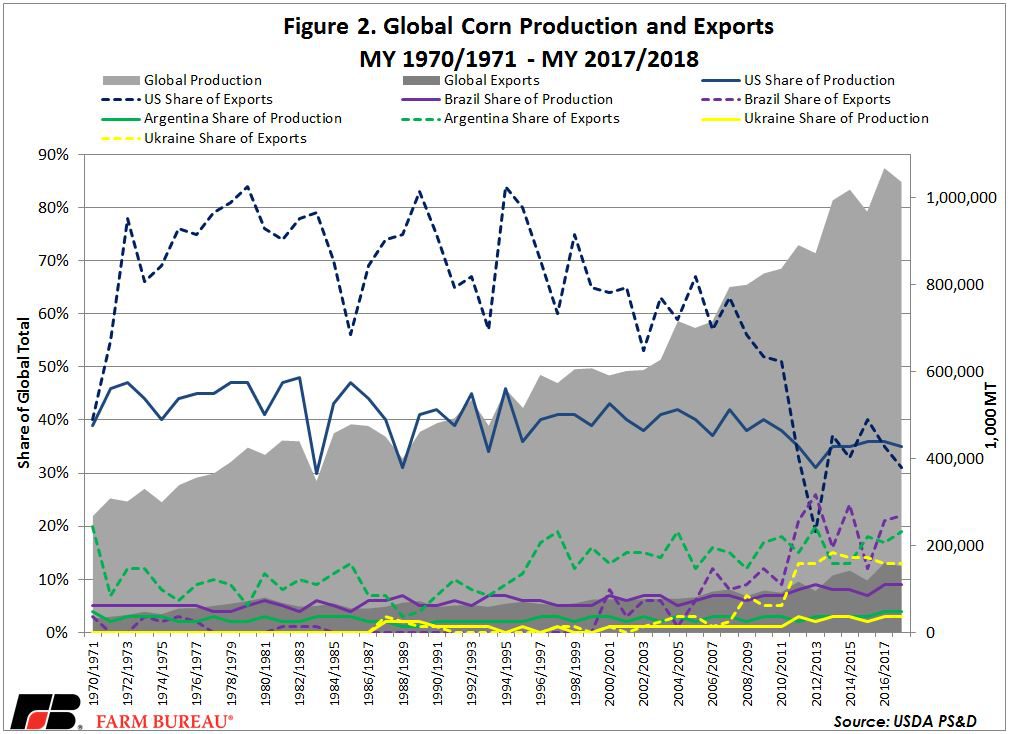

USDA’s Production, Supply and Distribution data showcases that the world of trade in corn has changed dramatically over the years. Back in the early 1970s the U.S. was really the only game in town. We produced 40-45 percent of the global corn supplies, which totaled between 300-350 million metric tons. The U.S. was also the source of 65-75 percent of global exports, which totaled 40-55 million metric tons. The U.S. continued, unrivaled as the leading producer and exporter of corn though the early 1990s when South America began picking up momentum as exporters. Argentina appeared first and was joined by Brazil in the mid-2000s. Figure 2 highlights the changes that have occurred over the last several decades.

The last decade, however, deserves special discussion. Figure 3 puts a spotlight on the emergence of Brazil, Argentina and the Ukraine as significant exporters over the last several years. In the 2016/2017 marketing year, Brazil, Argentina and the Ukraine were responsible for 21 percent, 17 percent and 13 percent of global corn exports, respectively, while the U.S. captured 35 percent. All the while, global production and exports of corn both reached new records at over 1 billion and 159 million respectively. It seems the questions as to whether our competitors are willing and able to supply the Mexican market have been answered.