Ag-Powered Fuels: 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) made several important changes to the Clean Fuel Production Credit (45Z). Most notably, it extended the credit through 2029, providing biofuels producers with an additional two years of investment beyond the original 2027 expiration date. While the credit still has no requirements to pass through any of the credit to farmers and feedstock producers, the OBBBA clarified key provisions related to feedstock eligibility, emissions measurement and credit calculation, which are especially relevant for U.S. farmers. This Market Intel analyzes what the changes to 45Z mean for farmers.

The Evolution of 45Z

The 45Z credit was established under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 to encourage domestic production of low-emission fuels. It is not tied to a specific type of fuel or production technology; it instead bases eligibility solely on a fuel’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional petroleum-based fuels. This credit was created to consolidate separate tax credits for biodiesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). The 45Z credit applies to fuel produced after Dec. 31, 2024, and was originally set to expire at the end of 2027. The OBBBA extended the credit to fuel sold by Dec. 31, 2029.

The 45Z tax credit is dependent on how much the eligible fuel reduces emissions and is claimed by biofuel producers. The emissions from feedstock production through fuel combustion is estimated using the U.S. Department of Energy 45ZCF-GREET (Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Technologies) Model. The GREET model consolidates all of the greenhouse gas emissions of each step of the biofuels supply chain, dependent on things like form of transportation and farming practices, into a specific emission rate for a gallon of fuel. This emission rate becomes your carbon intensity (CI) score; the lower the CI score, the higher the tax credit. To qualify, fuels must produce less than 50 kilograms of carbon dioxide per unit of energy – half of traditional petroleum products – for a base credit of 20 cents per gallon. The fuels that reduce emissions the most can earn biofuel producers up to $1 per gallon in 45Z tax credits.

GREET scores can be lowered in various ways, including on how the feedstock was produced. For example, the standard CI score for corn is 29.1. This means traditionally produced corn as a feedstock would largely not reduce emissions enough to qualify for 45Z credits. However, by utilizing conservation methods like no-till, cover cropping or high-efficiency fertilizers that affect carbon sequestration and release from soils, you can lower the CI score. While the GREET model was updated in January 2025, the OBBBA now requires the model to be adjusted again to exclude emissions from indirect land use change (ILUC)– the conversion of grassland, forestland, etc. to cropland to produce biofuels feedstock.

OBBBA also clarified that, to qualify for the 45Z credit, eligible fuels must be produced by American-controlled firms using feedstocks sourced from North America (the United States, Mexico or Canada). This change supports a broad range of agricultural feedstocks, including corn, soybeans and other biomass-based materials, expanding market opportunities for farmers while reducing reliance on fossil fuels. The amendment was designed to prevent large imports of used cooking oil (UCO), which had more favorable carbon intensity scores as it is considered a waste product with minimal lifecycle emissions. There was also increasing scrutiny over the possibility of fraud in imported feedstocks, as some UCO may be blended with virgin oils and falsely labeled as waste to qualify for higher credits.

The OBBBA also amended 45Z and Section 6426(k) to ensure that sustainable aviation fuel producers do not receive overlapping credits and removed premiums in the credit for SAF. Before passage of OBBBA, SAF could receive an extra 75 cents per unit of carbon reduced compared to other clean fuels. Lastly, the legislation increased credits for small producers to encourage blending capacity increase.

Effect on Markets

Many anticipate that the 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit, especially with changes made under the OBBBA, will increase demand for domestically sourced feedstocks. While the 45Z tax credit is awarded to fuel producers, not directly to farmers, it incentivizes fuel producers to increase production of eligible fuels and thus purchase additional feedstocks, creating the potential for more stable demand and stronger prices for key commodities tied to eligible fuel production.

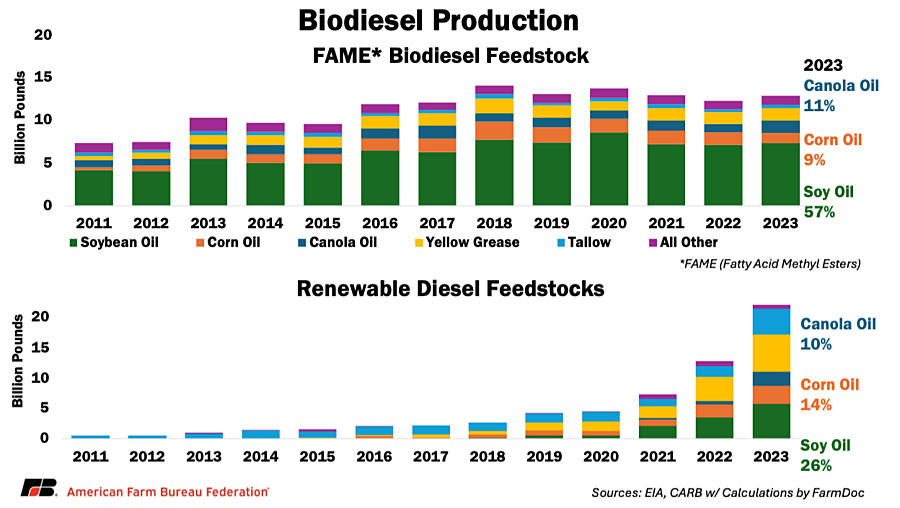

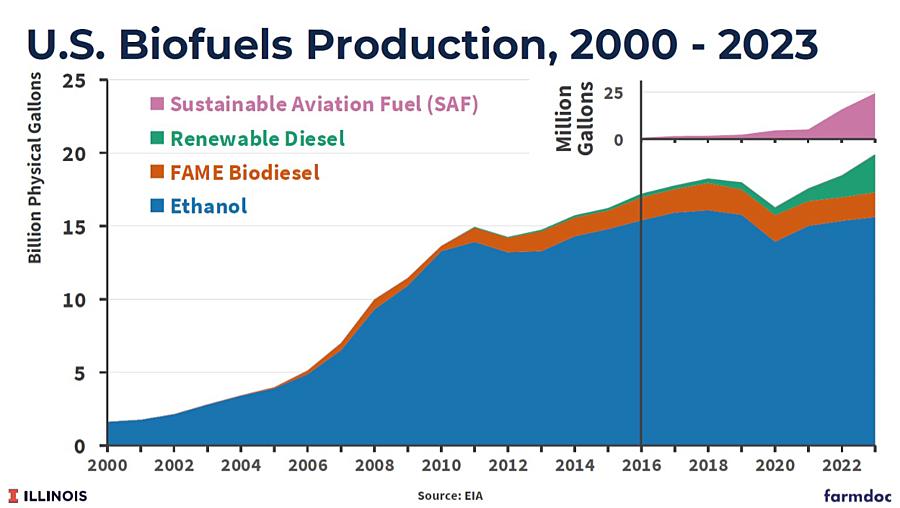

Renewable fuels are already a major source of demand for U.S. agriculture, particularly for corn and soybeans. USDA projects that 35% of U.S. corn production will be used for ethanol in 2025. Additionally, corn oil can be used in biodiesel production. At the same time, more than 50% of domestically produced soybean oil is expected to go into biofuels, including biodiesel and renewable diesel.

To meet these sourcing requirements, fuel producers can enter into arrangements with growers that can offer predictability and consistent pricing for the farmer on the contract. In addition, as fuel producers work to improve their carbon intensity scores to qualify for higher credit values, some may offer premium payments for feedstocks produced using low-carbon farming practices such as conservation tillage, cover cropping or improved nutrient management. However, these contracts may also come with burdensome and costly certification requirements to qualify. They also lock farmers into specific production practices in the long-term, limiting their ability to adapt to changing weather and market conditions.

Farmers may also benefit from increased demand for byproducts such as corn oil, soybean oil, crop residues and animal fats. These materials are being used more frequently in renewable diesel and the fledgling sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) market, expanding revenue opportunities and reinforcing the role of agriculture in the clean energy economy. Although farmers are not the direct recipients of 45Z credits, the indirect impacts through contracting, pricing and value-added markets position them to potentially benefit from this growing sector.

45Z Challenges

With the changes to 45Z in the OBBBA, the Department of Treasury and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) must now rewrite the regulations and guidance for qualifying fuels. This also requires USDA to finalize (or change) the interim technical guideline for “climate-smart” practices that lower CI scores for biofuels feedstocks. USDA has largely turned away from labeling conservation practices as “climate-smart.” In January, the Office of the Chief Economist at USDA released a list of 24 possible conservation practices or combinations of practices that could lower GREET scores for biofuels. Notably, they removed the previous requirements for 40B SAF tax credits that required farmers to conduct “bundles”, set combinations, of conservation practices, which added to the complexity of qualifying for biofuels credits and vastly limiting the eligible feedstocks. However, there is still time for the USDA to alter the eligible emissions-reducing practices.

It is also important to reiterate that there is no requirement for biofuels producers to pass any of their earnings from 45Z on to the farmers who produced their feedstocks. With rising global row crop production and low-profit margins creating uncertain market conditions for farmers, additional premiums from eligible biofuel feedstock sales can make or break farm balance sheets. However, the conservation practices required to sell crops as feedstock require significant upfront financial investments if farmers are not already utilizing them. Many factors impact what conservation practices are feasible in different regions and cropping systems. Cover crops are used on less than 5% of cropland, while, reduced tillage and no-till are used on 25% and 28% of cropland, respectively. The percent of land using a combination of any is likely also lower. And in the current down crop economy, it is difficult for crop farmers to invest in new machinery and inputs that would allow more cropland to use these needed feedstock conservation practices. If biofuels producers hope farmers continue to utilize and grow these practices on farms, they must provide significant premiums for feedstocks. Without guarantees that their investments will be returned through crop premiums or credit passthroughs, it will likely be slow going to grow eligible feedstock acres, particularly with only four years before 45Z faces expiration again.

Conclusion

Even with the OBBBA changes to 45Z eligibility, there are still many needed clarifications before the credit can be used. In addition, the uncertainty on whether farmers will be compensated for lowering emissions of feedstocks and downstream biofuels may make it difficult to truly maximize the growth of biofuels, as the 45Z credit was created to do.

Regardless, biofuels producers will likely begin planning how to take advantage of this extended tax credit. If federal agencies quickly provide workable guidance for 45Z, farmers can plan for future crop years to take advantage of the expanding markets for biofuels. When bumper crops are pushing down crop prices, increasing market demand is crucial for supporting crop prices and farm income. 45Z and biofuels production, particularly with the OBBBA investments in domestic feedstocks, represents a step forward in encouraging demand for major American crops. But without clear implementation and a fair path for farmers to benefit, the full potential of the credit may fall short.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL