Agricultural Imports 101

Daniel Munch

Economist

Trade is a hot topic with a lot of uncertainty. Trade policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., will impact farmers and ranchers in the countryside. This Market Intel is part of a series exploring agricultural trade, including the potential impacts of trade policy changes and Agricultural Exports 101.

The U.S. agricultural trade deficit has garnered significant attention, as the value of imported agricultural products now exceeds the value of what we export. Why do we import so many agricultural products, and where are these goods coming from? In today's Market Intel, we’ll address these questions.

Import Origins

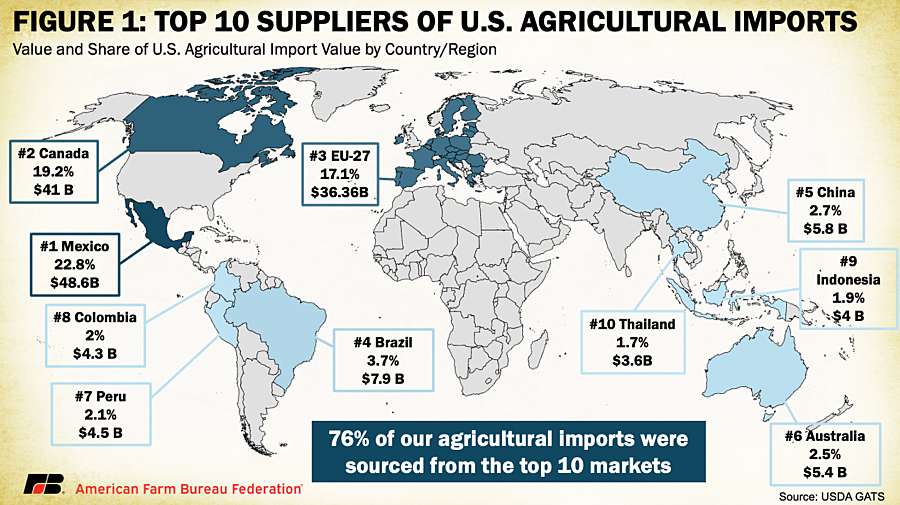

In 2024, the U.S. imported $213 billion in agricultural products from 184 countries and territories, representing over 6% of total U.S. imports. Seventy-six percent of these imports came from the top 10 suppliers, with Mexico, Canada and the European Union accounting for nearly two-thirds of the total agricultural import value. Since 2000, agricultural imports from these three partners have more than quadrupled, rising from $24 billion to over $102 billion. Mexico has held the top spot for U.S. agricultural imports since 2016, surpassing Canada.

What Food we Import

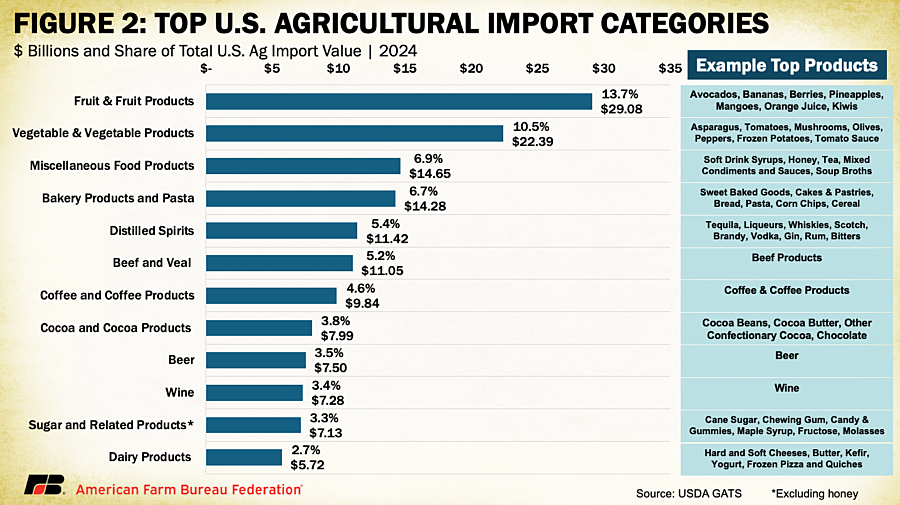

Before diving into why the U.S. imports so many agricultural goods, it helps to look at what we're bringing in. Of the total, nearly $149 billion, or 70%, fell under consumer-oriented products. These include everyday items you’ll find on grocery store shelves, like fruits and vegetables, which rank as the top two import categories. Intermediate goods, such as vegetable oils, sweeteners and baking ingredients used in food processing, accounted for $48 billion (22%). The remaining $16 billion (8%) consisted of bulk commodities — primarily unprocessed items like unroasted coffee, raw cane and beet sugar, cocoa beans, oilseeds, rice and tea. You may recall that bulk goods account for a considerably larger share of U.S. agricultural exports — 32% — underscoring a key difference in trade dynamics: while U.S. imports are dominated by high-value, consumer-ready foods, our exports lean more heavily on raw, unprocessed commodities like grains and oilseeds. In 2024 the U.S. also imported an additional $50 billion in ag-related products which included $25 billion in seafood products, $23 billion in forest products and $2 billion in biodiesel and blends.

Figure 2 highlights the top 12 agricultural import categories by value and their share of total U.S. ag imports.

Why we Import

So, why does the U.S. import so much food? It comes down to the fact that not all countries are created equal — each has its own mix of climate, natural resources, labor costs and cultural specialties that influence what they produce most efficiently. Some countries are simply better suited — whether by geography or skill — to grow, raise or make certain goods. That comparative advantage allows each country to focus on what it does best, and trade for the rest. From a consumer standpoint, this global specialization means greater access to the products we want, often at better prices, in greater variety and year-round.

Take climate, for example. Many tropical fruits are now staples in the American diet, but they require consistently warm, humid conditions to thrive. Bananas top the list, with 26.9 pounds available per person each year. While limited banana domestic production can exist in places like Hawaii, Puerto Rico and parts of southern Florida, these areas face land constraints and pressures like urban sprawl, making large-scale production difficult. Instead, countries like Guatemala, Ecuador and Costa Rica, our top banana suppliers, step in to meet demand. In fact, fruit and fruit products represented the largest share of U.S. agricultural imports in 2024 at $29.08 billion, or 13.7% of total ag imports, with tropical fruits contributing heavily to that total.

Coffee follows a similar pattern: it's deeply embedded in American consumption habits, yet virtually all of it must be imported (just 0.2% of U.S. coffee consumption came from domestic production in Hawaii and Puerto Rico). For exporting nations, this trade brings in valuable revenue that can be used to purchase goods and services they may not be able to produce themselves, completing the win-win cycle of global trade.

The Seasonality Factor

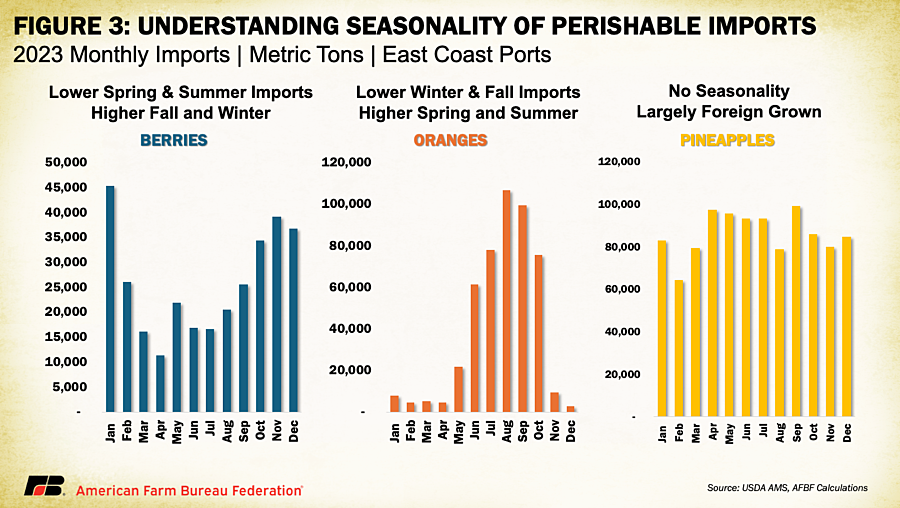

At the start of this year, concerns over a potential International Longshoremen’s strike threatened to disrupt operations at major East Coast ports, posing a serious risk to the steady flow of imported food products. At the time, we highlighted how the timing of a trade disruption — specifically, the season in which it occurs — can significantly affect its impact. That’s because the availability of domestic agricultural supply varies month to month. Americans are accustomed to having year-round access to a wide variety of foods, regardless of season, but that access often depends on imports. The global climate plays a key role in this dynamic, as production shifts across hemispheres. When one region is in winter or the rainy season, another may be in peak harvest. When U.S. fresh supply is out of season or limited, imports fill the gap.

Figure 3 highlights this seasonal dynamic. Berry harvests vary widely across the U.S. by variety and region, but there is generally a domestic shortage during the winter months. During this time, shipments of blueberries from Peru, for example, increase significantly to meet consumer demand. Conversely, oranges have robust domestic availability during the winter and spring, with imports peaking in the summer and fall. Pineapples, on the other hand, have a different pattern. With domestic production limited to Hawaii and Puerto Rico, pineapple imports remain steady throughout the year with little seasonality.

While imports often complement domestic supply, particularly in off-season months, they can also compete directly with U.S. growers producing the same crops during peak harvest. This is especially true for fruits and vegetables with narrow harvest windows, where foreign product availability can undercut prices or shift market share. These challenges are well known among seasonal produce growers and continue to raise concerns about fair competition and long-term viability.

Inputs Matter

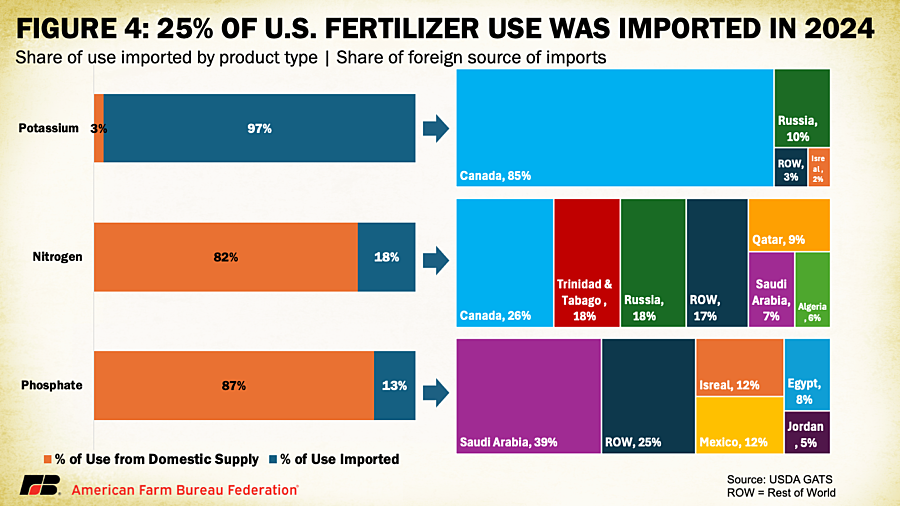

We could try giving up coffee, bananas and winter berries for a while, but the impact of disrupted imports goes far deeper than just what's on the grocery list. A significant portion of U.S. agricultural production depends on the global trade of critical inputs that make farming possible in the first place. Take fertilizer, for example. While the U.S. is the world’s third-largest fertilizer producer, it still lacks the domestic resources to meet total demand. Every country’s ability to manufacture fertilizer is shaped by its natural reserves, particularly mineral nutrients like phosphate and potassium, and the energy sources needed to extract and process them.

One key example: Canada possesses potash deposits not found in the U.S., which are essential for producing potassium-based fertilizers. In 2024, the U.S. imported 97% of its potassium fertilizer, with 85% of that coming from Canada. Although the U.S. has stronger domestic capabilities for nitrogen and phosphate, imports still accounted for roughly 25% of total fertilizer use. Without access to these imported nutrients, the productivity of many row and specialty crops would be severely compromised.

And it doesn’t stop at fertilizer. The U.S. farm sector also depends on foreign supplies of crop protection chemicals, equipment components and other essential inputs. China, for example, is the world’s top exporter of both phosphate fertilizers and active ingredients used in herbicides and fungicides. In fact, Chinese manufacturers produce nearly 70% of the world’s pesticide products, and the U.S. ranks among the largest importers. From farm machinery parts to seed treatments, U.S. farmers rely on a tightly connected global supply chain, making agricultural imports about more than just the foods we eat, but the means to grow them in the first place.

The Developed-Country Factor

An often-overlooked driver of the U.S.’s high level of agricultural imports is not just what we grow — or can’t grow — but who we are as a nation. The United States is a high-income, developed economy with one of the largest consumer markets in the world. With higher average incomes and a relatively low percentage of income spent on food, American consumers have the luxury of choice, and they exercise it. In fact, U.S. households spend just over 10% of their disposable income on food, one of the lowest shares globally. That financial flexibility allows Americans to be selective not only about what they eat, but where it comes from. We don’t just buy for sustenance, we buy for taste, convenience, novelty, health preferences and year-round availability.

Compare that to developing countries, where many consumers must prioritize price and basic availability over brand, variety or origin. Even if imported foods are technically available, they may be unaffordable or inaccessible for large portions of the population.

The U.S. is a world-class producer of many of the very same products it also imports. From California vineyards and Midwest creameries to the craft breweries dotting every state, domestic options are not only available — they’re thriving. Yet, many consumers still choose foreign options, because they can. The more purchasing power a population has, the more likely it is to seek out products that either complement or enhance the domestic supply — and that demand is met through global trade.

Labor Costs Strain U.S. Competitiveness

The lack of an affordable and reliable labor supply has created significant challenges for U.S. seasonal produce growers, who face higher labor costs than many of their global competitors. To put this into perspective, the 2025 required wage for temporary agricultural workers is $18.12 per hour, far above the $1.59 per hour earned by farmworkers in Mexico and the $4.50 per hour in Brazil. Labor costs are up to 40% of production costs for labor-intensive industries like fresh fruits and vegetables. These significant labor cost gaps, exacerbated by worker shortages, make it difficult for U.S. growers to compete on price. As a result, many are forced to rely on imports to meet demand, especially for labor-intensive crops. Addressing labor shortages through reforms to programs like the H-2A guestworker program could ease this burden, reduce the need for imports and ultimately help close the agricultural trade deficit.

Conclusion

The U.S. agricultural import story isn’t one of weakness, it’s one of complexity, necessity and consumer choice. Imports provide Americans with year-round access to diverse products and supply farmers with critical inputs needed to stay productive. But strong import flows shouldn’t be mistaken for a lack of domestic capability. The U.S. remains a global leader in producing high-quality food, fuel and fiber. Even so, a growing trade deficit and rising reliance on foreign inputs warrant attention. Structural challenges — from labor costs and regulatory burdens to shifting supply chains — have already pushed some specialty crop production offshore and continue to pressure others.

Imports and exports each play essential, often complementary, roles in U.S. agriculture. While exports open new markets for American producers, imports fill seasonal gaps, supply key inputs and broaden consumer choice. Understanding both sides of the ledger is key to navigating the challenges and opportunities ahead.