An Offal Lot of Potential

AFBF Staff

photo credit: Getty

On June 12, 2017, the final protocols were released for shipping U.S. beef to China. Of the requirements listed, a few highlights include:

- Beef and beef products must be derived from cattle that were born, raised, and slaughtered in the U.S., cattle that were imported from Canada or Mexico and subsequently raised and slaughtered in the U.S., or cattle that were imported from Canada or Mexico for direct slaughter;

- Cattle must be traceable to the U.S. birth farm using a unique identifier, or if imported to the first place of residence or port of entry;

- Beef and beef products must be derived from cattle less than 30 months of age;

China also bans the use of growth promotants, feed additives, and chemical compounds; and will conduct residue testing at port of entry on shipments of beef. This is one more important step forward to market access that could have a lot of potential for U.S. beef producers.

The Market:

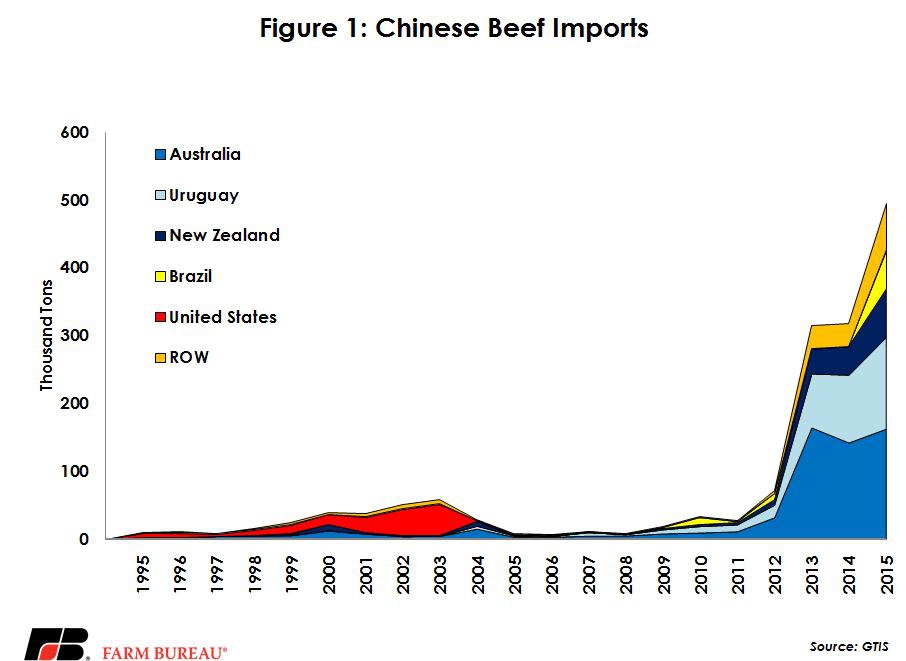

China has about 1.4 billion people and over the last five years, beef consumption has been climbing along with imports. Up until 2011 beef imports to China struggled to reach more than 50,000 tons, but in 2012 imports doubled. Over the next four years, imports would increase nine-fold, reaching 601,000 tons in 2016. U.S. market access was eliminated in 2003 as a result of BSE and over the last 14 years, Australia has taken the lion’s share of the business in this growing market, followed by Uruguay. Figure 1 shows the historic rise in beef imports over the last 20 years.

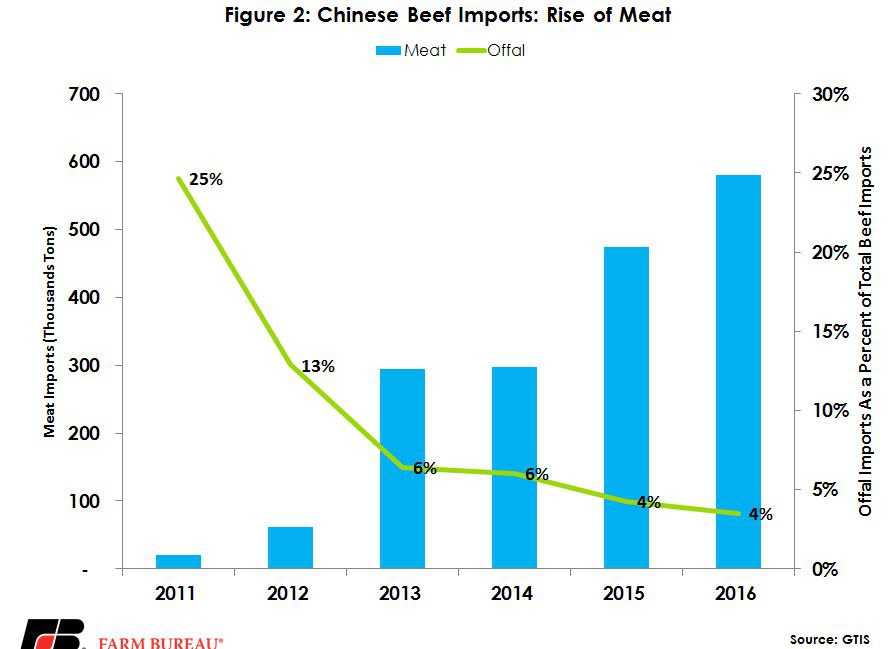

China is expected to become the largest beef destination in the world and has the potential to be a major destination for U.S. product. The market in China has changed substantially in those 14 years. Back in 2003, the U.S. supplied 80 percent of Chinese beef imports according to Global Trade Atlas. Of those 80 percent, more than 20 percent was offal, items such as tongues, kidneys, livers etc. As the demand for beef has grown in China, the amount of offal imports has grown as well but has been vastly outpaced by the rise in muscle cuts. In 2011 offal accounted for 25 percent of total beef imports to China, and by 2016 that number dropped to 4 percent, even though offal imports have increased three-fold since 2011. Figure 2 shows the change in meats versus offal imports.

Offal Market in the U.S.

In 2003 China was the seventh largest destination for U.S. frozen offal (HTS 020629), and the sixth largest destination for tongues. Today, Mexico and Japan are the top two destinations for offal. The U.S. ships almost all offal produced overseas. It is a critically important piece of the carcass value to find a home for these by-products that would not be used by the domestic market. One important thing to note is that as carcass weights have gotten heavier and dressing yields improved, indicating more meat has become available on a per carcass basis. However, it does not change the volume of organs. Cattle still have one tongue, one liver, two kidneys etc. The numberof offals available is directly tied to number of head moving through the system. The U.S. has rather consistently exported between 250 to 300 thousand metric tons of offal over the last 14 years.

Production System Changes

The ban on the use of growth promotants, feed additives, and chemical compounds greatly affects how much potential the Chinese market has. Because these production tools are accepted in the U.S. as a science based production practices, producing for the Chinese market will likely need to carry a premium to drive producers to adopt a production system to fit that market. The question then becomes at what price and volume will Chinese consumers pay, and how sensitive are they to price fluctuations. These are questions that the market will determine, but should be interesting to watch it unfold.

Economically speaking, this will further segment the market, driving farmers and ranchers to producea specific product for a specific customer. The number of producers are interested in satisfying that market may depend on the cost of changing and adopting new on farm traceability protocols as well as new management programs to achieve results without the use of banned substances. In the end, the premium attached to the Chinese market must warrant those changes.

The Chinese requirements will not be something that U.S. meat packers can sort in the cooler. Product will need to be grown to meet these specifications, starting at the cow-calf level to move through the system. This will slow the potential ramp up of any additional exports to China. Only a small proportion of commercial beef production would fit the current parameters surrounding this protocol.

This also could have some interesting implications in the offal market. As mentioned earlier, offal production is determined by the number of head slaughtered. A rapid increase in the demand for these products would require large numbers of cattle to fit the parameters in a different way than a rise in the demand for muscle cuts. These production requirements will need to be addressed at the whole animal level, but there could be short-term price adjustments as the U.S. supply chain tests the market.