Feral Hogs vs. Farmers: The Damage Price Tag

Daniel Munch

Economist

As Congress advances reconciliation negotiations several conservation and animal health programs remain in limbo — including feral swine management initiatives left out of the most recent farm bill extension. At the same time, updated data from the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program (NFSDMP) and the National Wildlife Research Center (NWRC) offers the most comprehensive economic assessment of the significant costs feral hogs impose on U.S. crop and livestock production.

This Market Intel highlights findings from the most comprehensive research to date on feral hog damage, which these new estimates put at over $1.6 billion in annual agricultural losses across just 13 states — covering impacts to livestock, pastureland and six major crops. These updated figures extend far beyond traditional crop losses, capturing broader economic consequences such as land-use changes, infrastructure damage and control costs. Together, the findings provide timely context for evaluating the scope of the invasive swine problem and underscore the value of coordinated eradication programs like the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Project, which has shown measurable success but currently remains unfunded.

The Pig Problem

Feral hogs are a highly adaptable and invasive species that have been found in more than 35 U.S. states. With reproductive rates that allow populations to double in as little as four months, their geographic range and damage footprint grow rapidly without intensive eradication efforts. These animals cause extensive harm to agriculture by consuming and uprooting crops, degrading pastureland, damaging fences and infrastructure and directly impacting livestock — including through predation on newborn animals and competition for feed and water. They also pose serious disease transmission risks to both domestic livestock and wildlife. Our previous analysis, Farmers, Ranchers Struggle with Hog-Wild Feral Swine Population, provides more background information on the major threat feral hogs pose to agriculture, the environment, people, pets and livestock.

Survey Background

To better quantify the full scope of feral hog damage, USDA’s NFSDMP, in partnership with the NWRC and the National Agricultural Statistics Service, conducted two coordinated surveys targeting both crop and livestock producers. In 2022, over 11,000 crop producers across 11 states were surveyed about six major commodities — corn, soybeans, wheat, rice, peanuts and sorghum — frequently impacted by wild pig activity. That effort, released in 2024, captured crop damage, planting shifts, property losses and control costs during the 2021 production year. A separate 2023 study reached over 8,000 livestock producers in 13 states to evaluate damages from predation, disease, pasture destruction and control expenses. Together, the surveys represent the most comprehensive economic assessment to date of feral hog impacts on U.S. agriculture.

Feral Hog Populations Widespread and Growing

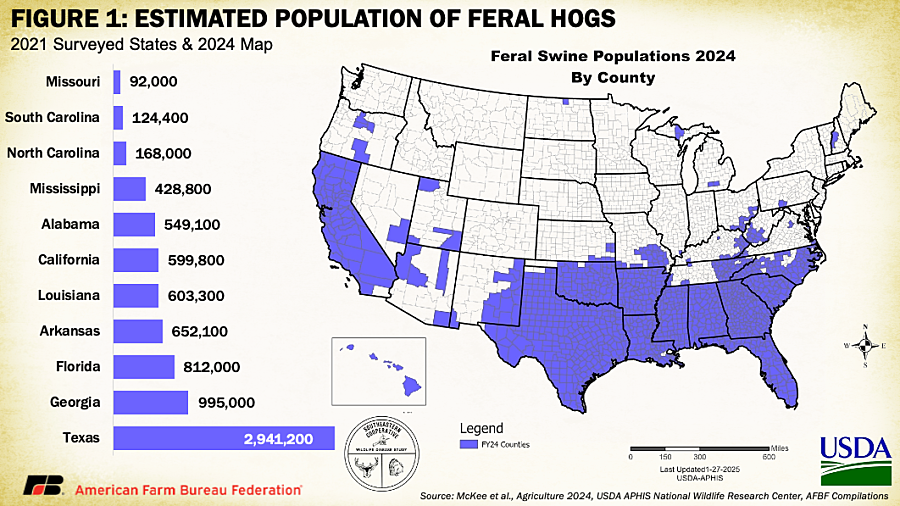

Feral hog populations remain firmly established across much of the Southern and Western U.S., with the highest concentrations in Texas, Georgia and Florida. Although primarily centered around warmer, Southern climates, feral hogs have successfully maintained growing populations in Canada and are well-documented surviving in extreme climates, making them well-adapted to thrive across North America.

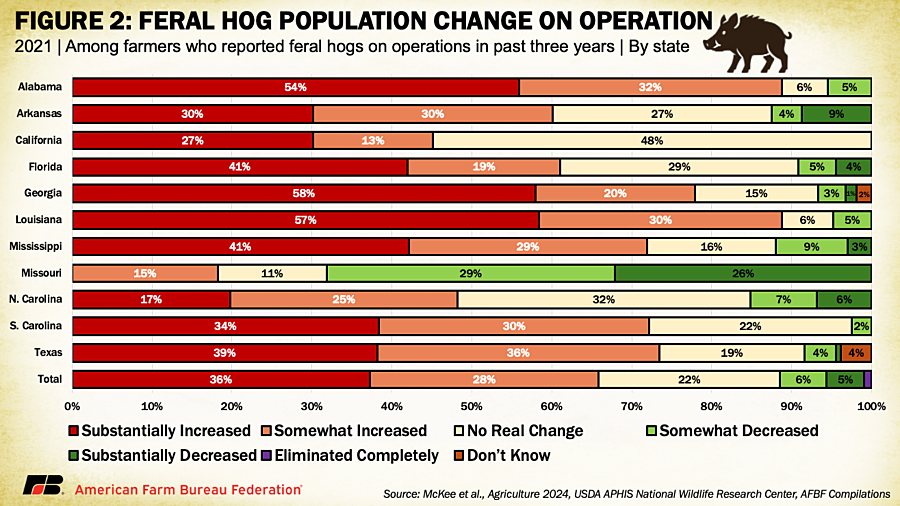

Findings from the crop producer survey reinforce just how widespread and resilient these populations have become. Among surveyed producers across 11 Southern and Western states, reports of on-farm feral pig presence were highest in Texas (73%), Louisiana (65%) and Georgia (63%). Importantly, a majority of producers in eight states — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas — said feral hog numbers on their land had somewhat or substantially increased over the past three years. Louisiana and Alabama stood out, with 87% and 86% of producers reporting a growing population, respectively, followed by 78% in Georgia. Missouri was the exception: only 3% of surveyed producers reported hog presence on their operation, and more than half said populations had decreased, likely reflecting the state’s coordinated feral hog elimination partnership. These producer-level observations mirror broader population estimates and reinforce a key pattern: in most areas, feral hog populations are either holding steady or increasing, making long-term control and reduction efforts especially important.

Feral Hogs: A Multidimensional Cost Burden

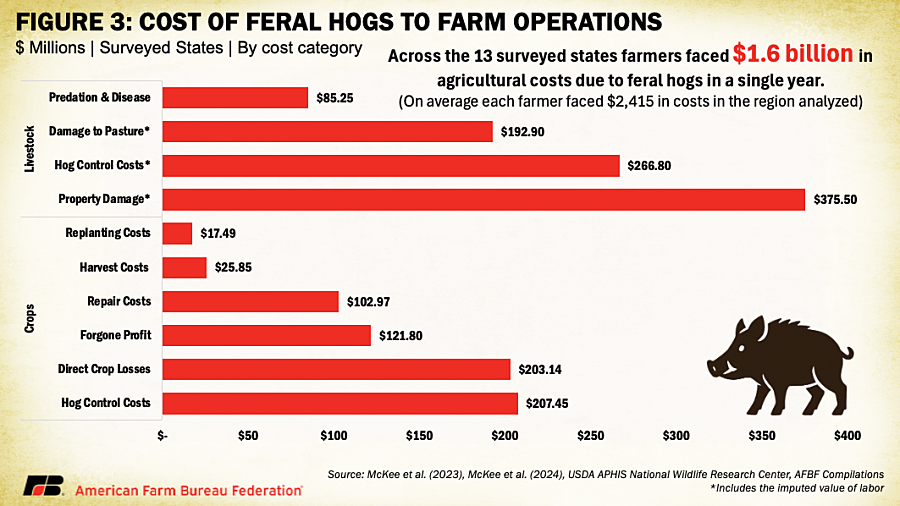

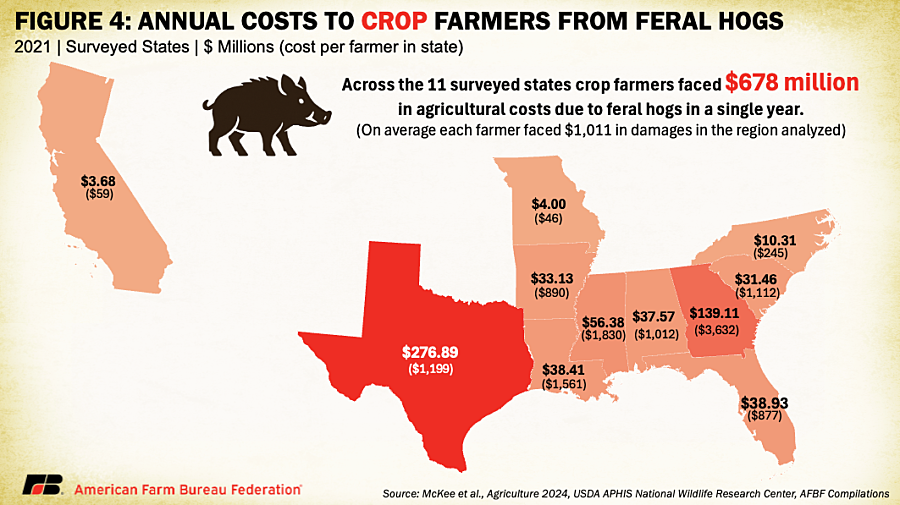

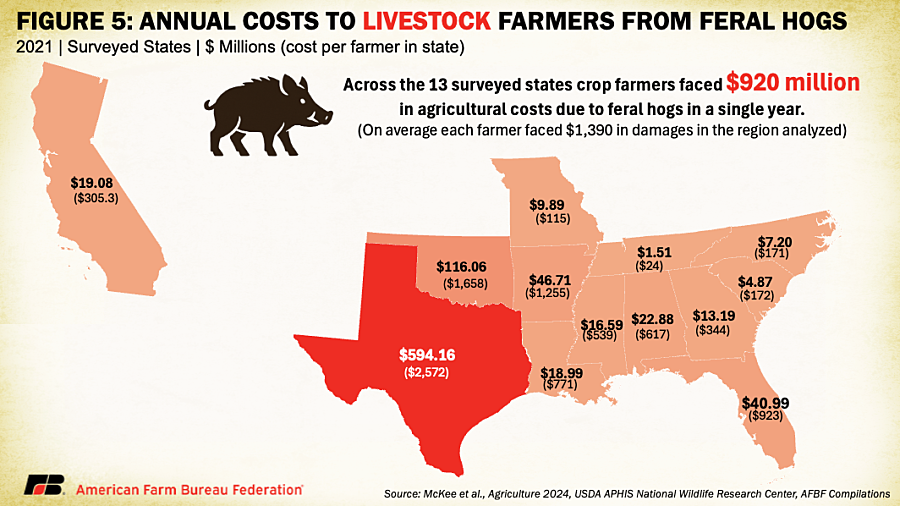

The NFSDMP and NWRC studies organize feral hog-related damages into key economic categories, offering the most detailed look yet at how these animals disrupt both crop and livestock operations. While crop losses often draw the most attention, the data shows that the true financial burden is much broader — influencing planting decisions, degrading pastureland, damaging equipment and infrastructure and consuming labor hours that could otherwise be devoted to production. Combined across 13 surveyed states, feral hogs caused an estimated $1.6 billion in agricultural losses in a single year. This total averages $2,415 per farm in the region — a steep cost from a single invasive species layered atop the many other pressures producers face. Total costs were highest in Texas ($871 million), Georgia ($152 million) and Oklahoma ($116 million).

Crop Production Losses – $203.1 million (Crops):

This category includes direct damage to standing crops caused by rooting, trampling and consumption. Wild pigs are opportunistic feeders, often targeting high-value crops like corn and peanuts but also affecting rice, soybeans, wheat and sorghum. On average, sorghum fields in counties with wild pig activity lost the highest share of their crop, about 6.4% of total production. Corn followed at 4%, then peanuts (2.8%), wheat (2.2%), and both soybeans and rice at 1.3%. By value, corn had the highest total production loss at $92.2 million, followed by peanuts ($38.5 million) and soybeans ($23.2 million). Texas alone reported $82 million in crop losses, the highest of any state. Georgia and Alabama followed at $37.5 million and $18.5 million, respectively. These repeated losses, often concentrated in a handful of fields, can quickly erode annual revenue and disrupt planting cycles.

Predation and Disease Losses – $85 million (Livestock):

Feral hogs inflicted roughly $85 million in livestock losses through predation, disease, veterinary costs and medical treatments. Sheep and goat producers suffered the highest percent loss rates from predation, but cattle operations faced the highest absolute dollar losses due to higher production value. Across predation, disease, veterinary and medical costs, cattle accounted for $61 million in losses ($35 million directly related to predation). Goats and sheep followed cattle at $10 million and $7.4 million, respectively. Hogs kill or injure newborn livestock, sometimes consuming the evidence, making losses hard to detect or misattributed to other predators. Hogs also spread serious diseases including pseudorabies, leptospirosis, brucellosis and vesicular stomatitis. Farmers spent over $9.2 million on medical treatment and veterinary services alone.

Pasture Losses – $192.9 million (Livestock):

Feral hogs caused an estimated $193 million in damage to pastureland, a critical resource for livestock producers. Nearly all cattle, sheep and goat operations rely on pasture, and in states like Texas, over half of producers with wild pig activity reported measurable pasture damage. This includes reduced forage availability due to rooting, erosion and weed incursion. Approximately 2.5 million hours were spent repairing pasture damage in 2020 alone. Producers also spent nearly $69 million on supplemental feed to compensate for the lost forage. These costs not only reduce profitability, they can restrict herd sizes and stocking rates, with some producers reporting reduced weights in animals as a direct result of degraded pasture.

Planting Changes & Foregone Income – $121.8 million (Crops):

Feral hogs didn’t just damage crops, they altered some farmers’ approach to planting. Among farmers who reported changing what they planted due to anticipated hog damage, 75% said the decision led to lost profit, amounting to $121.8 million across the surveyed region. The most significant losses occurred in Texas, where planting changes cost producers an estimated $60.1 million in 2021 alone.

When asked which crops they avoided, corn topped the list, with over half (53%) of affected farmers listing it among the crops they changed or reduced. Sorghum (21%), peanuts (20%), wheat (18%) and soybeans (9%) followed. Nearly four in 10 producers who changed crops said they didn’t plant anything in place of their original choice, leaving those acres idle or unutilized. Among those who did switch crops, many turned to soybeans (19%), wheat (13%) or cotton, which was the top alternative among those who selected a different crop entirely (32%).

These decisions reflect not just damage avoidance, but risk mitigation — farmers weighing the likelihood of a total loss against the cost of seed, fuel and labor. While switching crops can sometimes preserve a harvest, it often means sacrificing income by moving away from the most profitable or best-suited option for a particular field.

Replanting Costs – $17.5 million (Crops):

For farmers who chose to replant after initial damage, the added costs of seed, fuel, labor and equipment wear quickly added up. Replanting typically occurs under suboptimal timing or weather conditions and can increase vulnerability to late-season disease or reduced yields. The study estimates that about 9% of producers with hog presence had to replant at least one field due to damage, with many experiencing multiple rounds of replanting in a single season.

Harvest Disruption – $25.85 million (Crops):

Feral hogs frequently dig large wallows and rooting holes, creating uneven and rutted fields that complicate the operation of harvest equipment. This not only slows down the harvest process but also increases fuel use, heightens the risk of mechanical failure and raises safety concerns for operators. In wet conditions, these terrain disruptions can be especially damaging, leading to stuck machinery and missed harvest windows.

Property Damage – $102.9 million (Crops); $375 million (Livestock):

Feral hogs don’t just affect crops; they inflict serious and costly damage to the infrastructure that keeps farm operations running. Among crop producers, 60% reported physical damage to fields, and 37% reported damage to fences — critical for managing land use and protecting livestock. These repairs are not only expensive but time-consuming, pulling labor away from essential activities during peak production periods. In 2021, producers involved in the 11-state crop-focused survey reported more than $103 million in property damage, with Texas alone accounting for nearly $51.4 million. Common damage included access roads, irrigation systems, grain storage areas and vehicles. Vehicle repairs averaged over $7,100 per incident, and irrigation systems required an average of 164 labor hours to fix, an expense that grows quickly when farm labor costs are factored in.

When livestock operations are included, the damage picture becomes even more alarming. According to the survey of livestock producers across 13 states, feral hogs caused an estimated $375 million in property damage in 2020 alone, more than triple the crop-only estimate. This includes damage to fencing, waterers, feed and hay storage, pasture roads, erosion infrastructure and working facilities, all critical to livestock care and containment. These farmers reported over 7.1 million labor hours spent repairing this damage, with Texas once again absorbing the brunt at nearly $239 million in property costs. For ranchers, infrastructure damage isn’t just an inconvenience, it compromises animal welfare, increases vulnerability to predators and disrupts water and feed delivery systems.

Feral Hog Control Costs – $207.5 million (Crops); $266.6 million (Livestock):

Managing feral hog populations is time-intensive, costly and often falls squarely on the shoulders of farmers and ranchers. In 2021, crop producers across the surveyed region spent an estimated $207.5 million on control efforts. These efforts include expenses for fencing, bait, traps, ammunition, aerial control and — most significantly — labor. Crop producers collectively reported spending 4.9 million labor hours on feral hog control across the 11 states.

On the livestock side, farmers spent more than $266.6 million and 12.4 million labor hours managing hogs on their operations — more than double the crop sector’s labor burden. Most of this effort was carried out directly by farmers or their families, with only 4% of livestock producers reporting control assistance from a federal, state or county agency.

The methods used were largely similar across crop and livestock operations, with “shoot on sight” and trapping being the most commonly reported. Livestock producers also reported damage reduction from fencing, though only a small minority used electric or permanent exclusion fencing — likely due to the high upfront cost and limited support for implementation. Across both crop and livestock farmers, Texas farmers spent the most on hog control ($121 million), followed by Georgia ($55 million) and Florida ($27 million).

While many producers do what they can to mitigate damage, the combined $474 million and over 17 million hours spent annually across both crop and livestock sectors underscores how much is required just to maintain the status quo. Without coordinated, large-scale control strategies, individual landowners are left battling a highly mobile, fast-reproducing invasive species with limited tools, mounting costs and little external support.

Federal Eradication Programs: Proven Tools in Need of Continued Support

Recognizing the mounting threat feral swine pose to agriculture, Congress established the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program (NFSDMP) in 2014 under USDA’s APHIS. This program was designed with two clear operational goals: (1) eliminate feral swine in states where populations are low or newly emerging and (2) reduce populations where they are widespread to minimize ongoing damage. Since its inception, NFSDMP has removed over 570,000 hogs, eliminated populations in five states and moved 18 states into lower severity categories, demonstrating its value as a responsive and adaptable management tool. New research estimates that by slowing the spread of wild pigs, the program safeguarded $40.2 billion worth of agricultural and ecological resources between 2014 and 2021, protecting more than 60 million acres of field crops, 118 million acres of pasture and nearly 38 million livestock head from damage. These findings underscore that NFSDMP has delivered not only measurable population control, but also significant protection for production systems that would otherwise be under threat.

Building on that success, the 2018 farm bill authorized a companion initiative, the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program (FSCP), with $75 million in funding to be jointly administered by USDA’s APHIS and the Natural Resources Conservation Service. The program has supported 34 active projects across 12 Southern states, targeting some of the nation’s most heavily impacted agricultural regions. These projects combine on-the-ground hog removal by APHIS, restoration activities by NRCS and direct assistance to landowners through cost-share programs and community-led cooperatives.

Projects varied based on local needs, but all shared one goal: suppressing hog populations at a landscape scale. In Alabama, for example, producers across 173,000 acres participated in trapping initiatives that were credited with improving crop yields and water quality. In Georgia, corn yield losses dropped from 65% to 14% following project implementation, while in Mississippi, producers saved 85 hours per month on control efforts, translating to substantial labor cost savings.

Despite these results, the FSCP was not included in the most recent extension of the 2018 farm bill. Unlike many permanent farm bill programs, FSCP was established as a temporary pilot initiative without baseline funding, meaning it was not guaranteed continued funding beyond its initial authorization. When Congress passed a short-term extension in 2024, only programs with permanent funding authority were automatically carried forward, leaving FSCP out. Although the House recently passed a reconciliation package that includes the FSCP, the Senate has not yet taken up the measure. As the process continues, the exclusion of this proven and well-received program raises concerns about the continuity of federal support for feral hog control, particularly in states where populations continue to grow and where local funding is limited. Pilot participants and researchers alike have pointed to strong landowner participation, operational success and measurable reductions in crop and infrastructure damage as evidence of the program’s efficacy.

Conclusion

Feral hogs are a persistent and costly threat to U.S. crop and livestock production, inflicting over $1.6 billion in damages annually, including considerable labor costs at a time when finding and affording good help is one of the farmer’s biggest challenges. The latest USDA data confirms what many producers have long known: managing wild pig populations requires significant time, money and coordination.

At the same time, certain federal efforts, particularly through the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program and the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program, have demonstrated meaningful results. With the House having passed its reconciliation bill, which includes funding for feral swine management, attention now turns to the Senate to determine the program’s future. This new data offers timely insight into the economic stakes of feral swine management and the positive role federal coordination can play in supporting farmers on the front lines of this ongoing challenge.

The recent detection of pests like New World screwworm in Mexico further highlights the value of robust animal health defenses, including continued investment in invasive species and disease control efforts, to protect agricultural viability.