Port Strike Could Sink Access to Foreign Markets

Daniel Munch

Economist

A looming U.S. East Coast port strike would have severe consequences for food and many other farm products shipped from American farm and ranch families to international buyers. This article outlines the far-reaching effects that might result if the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) and the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX) cannot come to an agreement before their contract expires on Sept. 30.

The ILA is the largest union of maritime workers in North America, representing nearly 85,000 longshoremen across the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, Great Lakes, major U.S. rivers, Puerto Rico, Eastern Canada and the Bahamas. Their members load and unload cargo at ocean port terminals, particularly in container and roll-on/roll-off operations. On the employer side, USMX represents approximately 40 ocean carriers and terminal operators where ILA members work. The union is reportedly seeking wage increases exceeding the 32% won last year by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which represents many West Coast port workers. Additional demands include a higher starting wage for new employees, enhanced health care benefits, increased employer contributions to retirement plans and keeping provisions that prohibit automation to prevent job losses.

What’s at Stake in a Port Strike

Exports

In 2023, over 143 million metric tons of agricultural products, worth over $122 billion were transported through ocean ports. This represented just over 70% of U.S. agricultural exports value and 75% of volume. On the import side, U.S. ports received over 39.4 million metric tons in agricultural products, worth over $110 billion and accounting for 56% of imports by value. These figures highlight how crucial ocean ports are to U.S. agricultural trade.

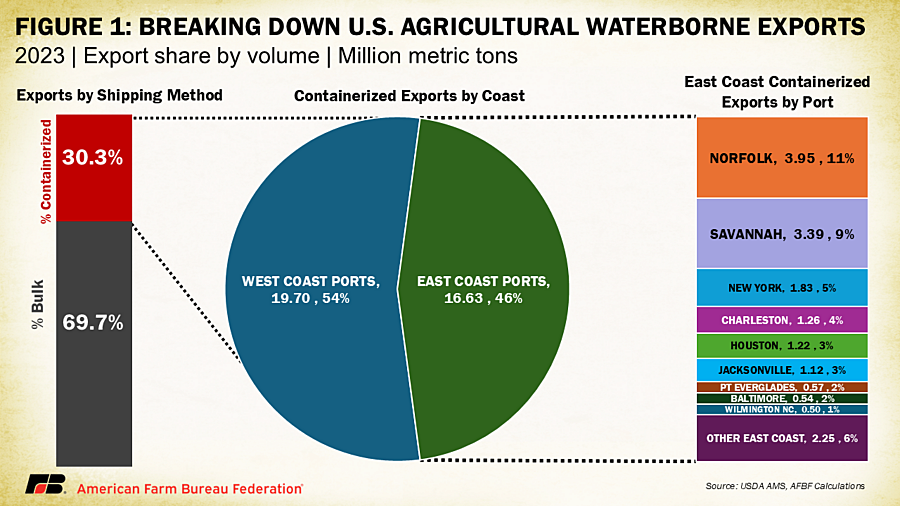

Should the threatened strike occur, the most significant disruptions would be felt in containerized agricultural exports, which compose just over 30% of U.S. waterborne agricultural exports by volume. The remaining 70% are raw, unprocessed commodities like grains, oilseeds, pulses, rice and animal feed, which are typically transported on specialized bulk carriers that are loaded and unloaded at dedicated facilities that often operate with non-ILA unions or independent workforces.

In addition, the strike will only impact U.S. ports with ILA workers, primarily along the East and Gulf coasts. Notably, about 46% of containerized agricultural exports, or 16.6 million metric tons, depart from East Coast ports. Of these, nine major ports account for nearly 94% of all East Coast containerized agricultural exports, with Norfolk and Savannah in the top two spots. In total, approximately 14% of all U.S. waterborne agricultural exports, by volume, would be at risk in the event of an ILA strike. Over a one-week period, the potential value of disrupted containerized ag exports is estimated at $318 million.

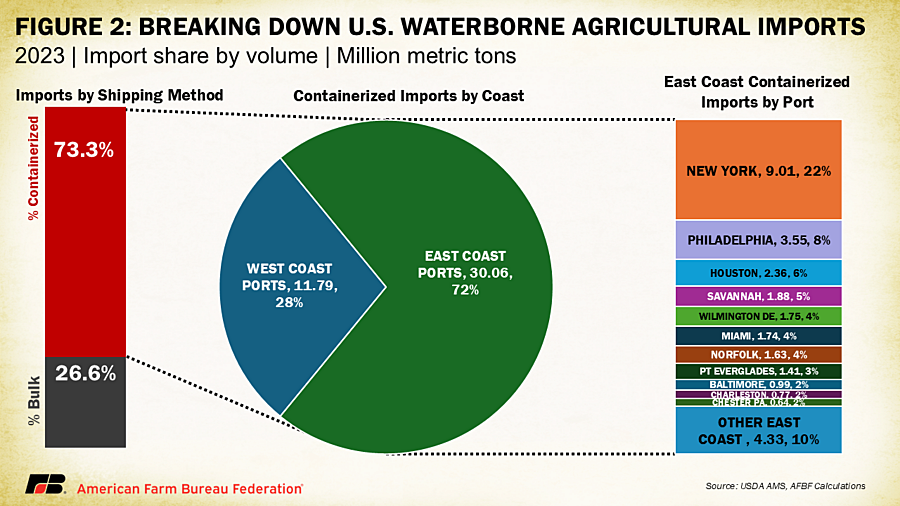

Imports

On the import side, containerized products play a much more significant role, representing 73% of all waterborne agricultural imports. The East Coast is crucial for these imports, handling 72% (30 million metric tons) of containerized agricultural imports. The top ports for these imports include New York, Philadelphia and Houston, with 11 ports accounting for nearly 90% of all containerized agricultural imports. In total, 53% of U.S. waterborne agricultural imports, by volume, could be affected by an ILA strike, leading to a potential economic impact of over $1.1 billion per week. Collectively, the value of containerized agricultural products passing through ILA-controlled ports, including both imports and exports, exceeds $1.4 billion per week.

Soybeans, Poultry and Other Commodities at Risk in Port Strike

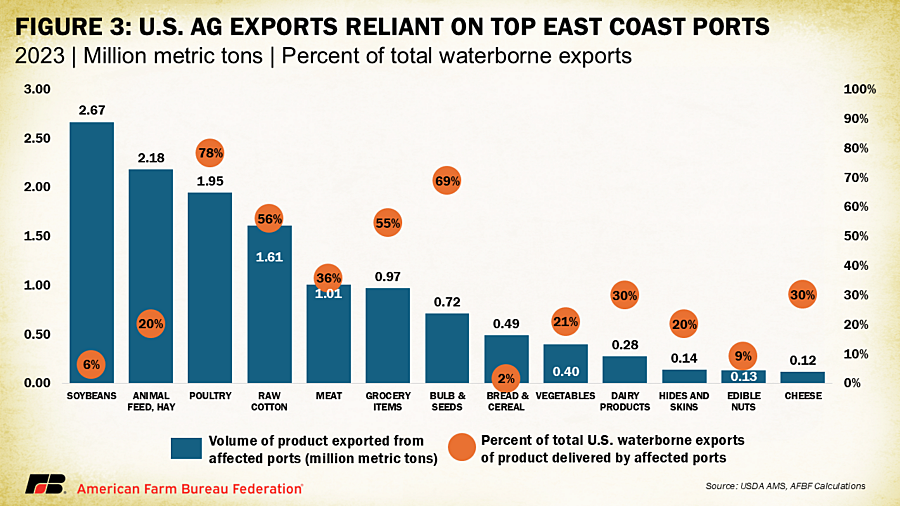

While the bulk nature of grain shipping shields most grain exports from an ILA-related disruption, there are exceptions. Notably, 2.67 million metric tons of soybeans were exported through East Coast ports in containers in 2023, representing 6% of U.S. waterborne soybean exports, according to USDA-Agricultural Marketing Service data.

Cutting off this vital outlet for producers is particularly biting when soybean producers are expected to harvest a record crop, and estimates of stored soybean stocks were up 22% over last year. The most immediate economic consequence for producers facing logistical bottlenecks is a sharp decline in basis. Basis represents the difference between the local cash price of a commodity which a producer receives and its corresponding futures price. When producers are unable to move crops to market, the local supply builds up. This excess supply, coupled with limited demand due to export disruptions, widens the negative basis. Soybean producers near Norfolk, Virginia — which handles over 60% of East Coast containerized soybean exports — could feel the greatest impact. Slowing exports also exacerbates storage shortages, further depressing prices.

Other commodities will feel an even greater impact than soybeans. Nearly 80% of waterborne poultry exports would be jeopardized, lowering prices for poultry producers as they lose vital market access. Additionally, impacts to poultry production would create upstream effects for feed suppliers, especially those producing corn and soymeal, which are essential feed ingredients for broiler operations. The Port of Savannah is responsible for nearly 50% of East Coast containerized poultry exports.

In addition, a strike at these ports would also disrupt significant quantities of other agricultural exports, including hay, cotton, red meat, vegetables, dairy products and edible nuts.

Where are These Agricultural Products Headed?

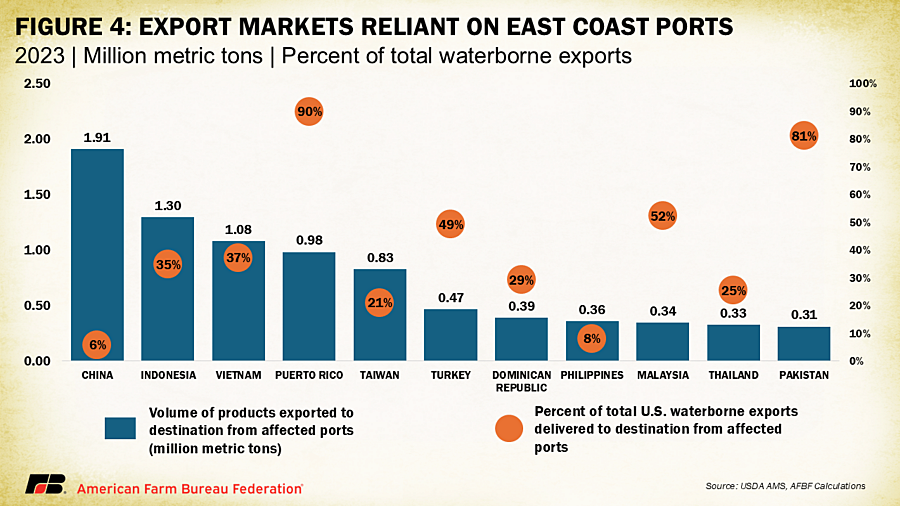

In 2023, the U.S. exported 1.91 million metric tons of containerized agricultural goods to China, accounting for 6% of our total waterborne trade with the country. We also shipped 1.3 million metric tons to Indonesia, representing 35% of U.S. waterborne trade with this key partner, and 1.08 million metric tons to Vietnam, making up 37% of our waterborne trade there. These nations ranked as the first, eighth, and 10th largest trading partners by volume for U.S. agricultural exports in 2023, respectively.

Closer to home, the 3.2 million American citizens in Puerto Rico could face significant challenges during an ILA strike, as over 85% of the island's food supply comes from the mainland U.S., with 90% of those shipments passing through ILA-staffed ports.

Port Strike Will Affect Consumers, Too

Each year, more than 3.8* million metric tons of bananas arrive at ILA-handled ports, supplying over 75% of the nation’s bananas. Beyond bananas, delays and shortages would occur for a wide array of everyday items. Price increases are a possibility as well. Nearly 90% of imported cherries, 85% of canned foodstuffs, 82% of hot peppers, and 80% of chocolate that arrive via waterborne vessels are offloaded from containers at these ports. The situation is similarly significant for beverages transported by vessel, with 80% of imported beer, wine, whiskey, and scotch, as well as 60% of rum, arriving in containers at East and Gulf Coast ports. Over 100 other food categories also depend on the smooth operation of these ports.

Are There Other Options?

Redirecting exports through unaffected West Coast ports can provide relief to both producers and consumers. This strategy is particularly effective for the many products destined for Asia. Retailers and importers of non-agricultural goods have already accelerated shipments in anticipation of strike-related delays, hoping to secure holiday inventory ahead of time.

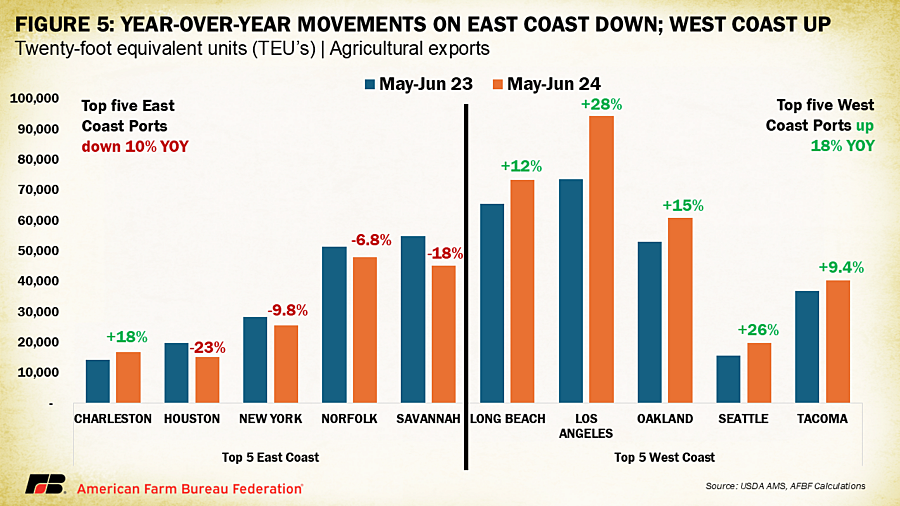

This shift is reflected in the changing container activity along both coasts as tracked by the USDA. Between May and June 2023 and the same period in 2024, agricultural product container volumes (measured in 20-foot equivalents) dropped at four of the top five East Coast ports but rose significantly at the top five West Coast ports handling agricultural trade. For example, agricultural exports from Los Angeles increased by 28%, Seattle by 26% and Oakland by 15%.

The critical challenge will be how effectively the domestic and global supply chains adapt to the shifting container movements, and whether certain regions might be left vulnerable, lacking access to efficient and cost-effective transportation options. Additionally, all ports face infrastructural limitations in how many containers they can process, meaning only a fraction of exports can realistically be rerouted.

Conclusion

With more than $1.4 billion in containerized agricultural goods passing through East and Gulf coast ports each week, a strike would create backlogs of exports, denying farmers access to a higher price in the world market, leading to a domestic oversupply, driving down prices for key commodities including meat and poultry, cotton, soybeans and specialty crops and further eroding farm profitability. On the import side, shortages and delays would raise costs for consumers — particularly for perishable goods.

While some relief may come from redirecting exports to West Coast ports, this strategy will be less helpful for regions that are further from these ports, increasing transportation costs and logistical hurdles for smaller producers. As the agricultural sector braces for rising operational costs, supply chain shifts and another likely downward pressure on commodity prices, U.S. farmers are finding themselves in an increasingly precarious position.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article omitted the Port of Wilmington, Delaware, in its calculation of banana imports. Including this port raises the total from 1.2 million metric tons to 3.8 million metric tons. In 2023, Wilmington, Delaware, accounted for 27% of banana imports.