2025’s Latest Hit to Farm Labor Costs

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

On Aug 25, 2025, in Teche Vermilion Sugar Cane Growers Association Inc., et al. vs. Lori Chavez-DeRemer, et al., a U.S. district court in Louisiana vacated the 2023 disaggregation rule nationwide. In a following statement, DOL said it would comply with the ruling and proceed appropriately through the Federal Register.

The Department of Labor’s (DOL) 2023 reclassification of some H-2A workers’ job titles continues to push wages higher, with another increase on the way this year per the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) 2024 Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS), which was released in April.

In 2023, DOL changed its longstanding Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) methodology to set distinct hourly wages for any job description with duties the department believes go beyond the six farm occupations included in USDA’s Farm Labor Survey (FLS). Since farmworkers, particularly those on small farms, perform a variety of job functions, this rule, known as the “disaggregation rule,” has resulted in some farm positions being reclassified to higher wage categories.

New Wages

While 96% of H-2A workers are still classified as farmworkers, graders and sorters, packers and packagers, or agricultural equipment operators – the classifications set by the FLS – some alternative job classifications have become more prevalent since the 2023 methodology was set.

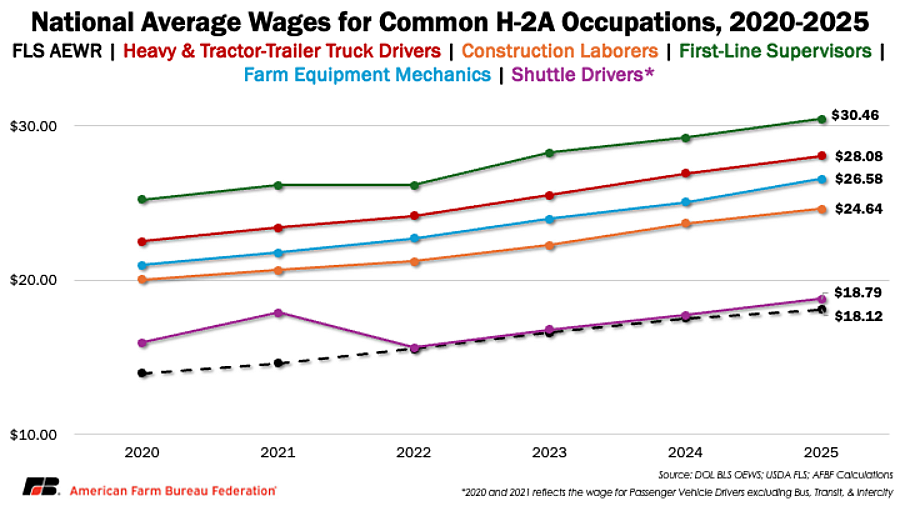

The five most common disaggregated occupations at the end of fiscal year 2024 were heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers (1.5%), construction laborers (0.6%), first-line supervisors of farmworkers (0.1%) and shuttle drivers (0.5%). Farm equipment mechanics (0.2%) have also climbed into the top 10 occupations in year-to-date fiscal year 2025 positions. The OEWS does not survey farms. Wages in this survey reflect workers in these occupations in the larger economy, like chauffeurs in New York City or long-haul truckers driving Amazon trailers from coast-to-coast. The additional qualifications and permits needed for these jobs in other industries mean that their wages are often much higher – sometimes more than $10 per hour higher.

The disaggregation rule requires that workers be paid the highest possible wage for their job duties for the entirety of their job contract, no matter how often they perform the task. In some states, the difference between OEWS and FLS wages are even more drastic than the national differences: In California, construction laborers – who could simply be those required to repair fencing on the farm – make $11.83 more per hour than farmworkers, while supervisors in Georgia make $18.61 more per hour, more than twice the wage of farmworkers. So, the traditional farmworker AEWRs have become a true minimum for H-2A wages – despite already being more than two times the federal minimum wage – and some duties a farmworker may only seldomly perform can as much as double farmers’ labor costs for the season.

The Hit to Farmers’ Checkbooks

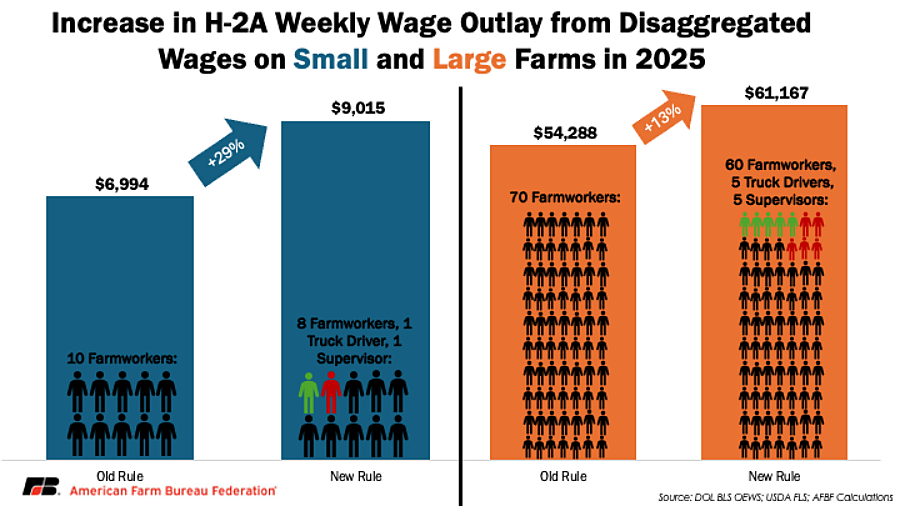

These increases to hourly wages add up fast. To illustrate this, we recreated a limited example that we first used when the rule was introduced. A small farm in this scenario hires 10 H-2A workers that were originally all paid the combined field and livestock worker wage from the FLS. They work a combination of 42 or 50 hours a week during peak harvest. After the disaggregation rule, one employee was reclassified as a first-line supervisor and the other is a heavy and tractor-trailer truck driver, both of which work 50 hours a week. (Note: in our original analysis, AFBF economists assumed one would become a light truck driver. We have switched this to a heavy truck driver in this analysis as it is a more common H-2A occupation). The large farm scales this up to 70 employees who are split up to disaggregated occupations of 60 farmworkers, five first-line supervisors and five heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers.

Using national average wages, the small farm’s wage expenses increase around 30% a year, and large farms increase over 10% a year. These increases have contributed to pushing labor costs to record levels, forecast at over $53 billion across the agricultural industry in 2025. While specialty crop revenues are expected to increase modestly this year, margins are still slim, and every additional cost risks the profitability of American farmers.

Farmworker wages are already subject to volatile year-to-year changes: the 2025 AEWR changed anywhere from a 10% increase to a 2% decrease, depending on the region. Each year since 1987, H-2A users have had to plan for a rise in their yearly wage in December or January based on the FLS, with no clues as to much their expenses would change. In the past decade, these yearly spikes have become even more dramatic with the 30% increase in the AEWR in the last five years. The disaggregation rule goes beyond this to add a second yearly increase that farmers are unable to forecast. Nationally, heavy and tractor-trailer truck driver wages have risen 25% in five years, with yearly increases in 2025 ranging anywhere from 2% in North Carolina to 6% in Washington.

Finally, the disaggregated rule also adds administrative hurdles for H-2A users who must update their payroll systems for a second time each year when the OEWS is release, some with no grace period to implement the wages. OEWS and FLS wages are also set at different levels for most states: each state has their own occupational wage in the OEWS, while there are 15 multistate regions in the FLS. Colorado wages have also been suspended in the OEWS this year, so national average wages will be used for each occupation instead. All of these discrepancies and changes require extra administrative work for farmers and ranchers to follow H-2A regulations correctly in a program that is already difficult to navigate independently.

Conclusion

Fruit and vegetable producers spend up to 40% of their production expenses on labor alone to ensure that fresh produce is available across the country. We continue to import more fresh produce from countries that pay as little as one-tenth the hourly wage that American producers pay because they can sell their products for cheaper prices while still turning a profit. H-2A guestworkers are vital contributors to U.S. specialty crop production as we continue to face a shortage of Americans willing to work on farms and ranches, but the costs required to use this program go well beyond what an employer would pay in taxes if they could hire an American. The disaggregation rule has continued to drive up wage expenses for U.S. farmers, putting American specialty crops at a continued disadvantage in the global marketplace.