African Swine Fever in China Keeps Getting Worse

TOPICS

TradeMichael Nepveux

Former AFBF Economist

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Cole Staudt

Michael Nepveux

Former AFBF Economist

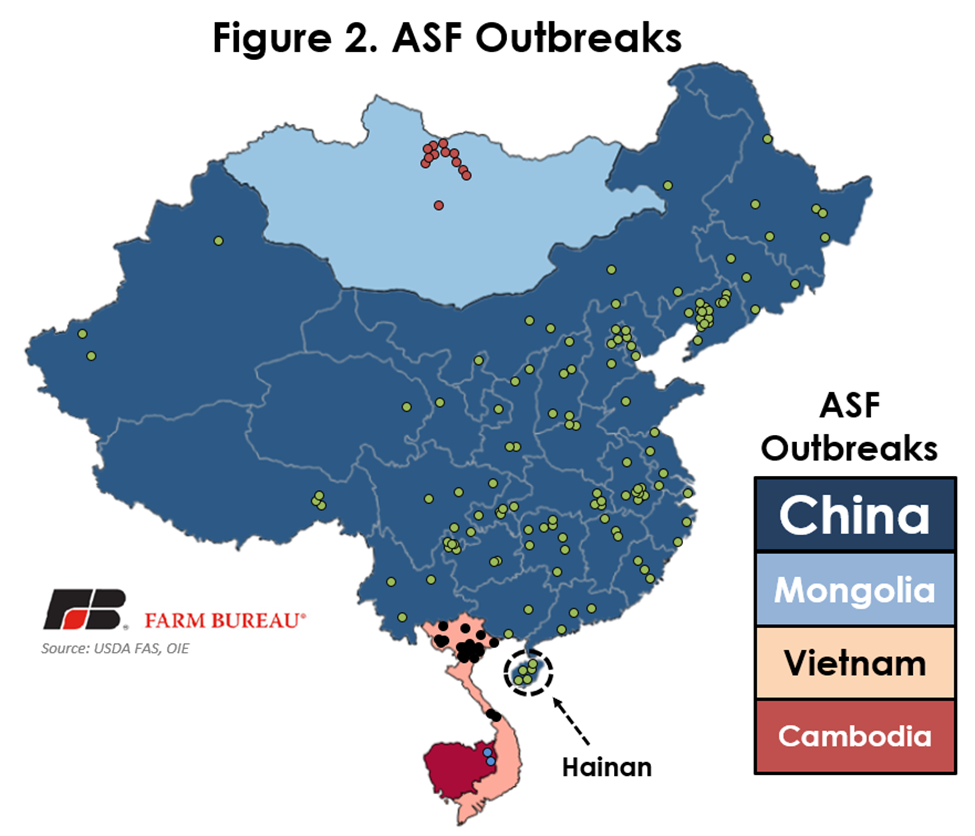

In the several months since I reviewed the African Swine Fever situation there have been several developments. First, the disease has spread from China to neighboring countries. Second, the number of officially reported outbreaks has jumped from 40 cases to more than 120. In addition, the number of OIE officially reported hogs culled has grown from 200,000 to over 1 million animals culled, or dead. Pretty much everyone who is following this issue believes that those numbers are largely underreported and that the actual number of outbreaks and the dead or culled animal numbers are far graver. The impacts of ASF have roiled global pork markets, with countries around the world taking steps to ensure it does not cross their borders; The U.S. has gone so far as to cancel the beloved World Pork Expo. This disease will very likely continue to significantly disrupt global meat markets and will have long-lasting ramifications for the world’s pork market.

ASF Spreads Through, and Beyond, China

Now in every single province in China, ASF is wreaking havoc on the world’s largest hog herd. Earlier in 2019, the number of officially reported outbreaks began to slow to a trickle, while unofficial and media reports picked up steam. There is no vaccine for ASF, which kills almost all pigs that become infected with it. The strength and severity of the disease, when combined with China’s inability to stem its spread, has led to significant decreases in animal numbers within the country. China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs reported that the March herd had dropped by nearly 19% relative to a year ago. More concerning is the reported drop in the breeding sow inventory to 21%, significantly jeopardizing future pork supply. Shandong, a major hog-producing region in China, is reported to have seen its breeding sow numbers drop a staggering 41% since the outbreak began last August.

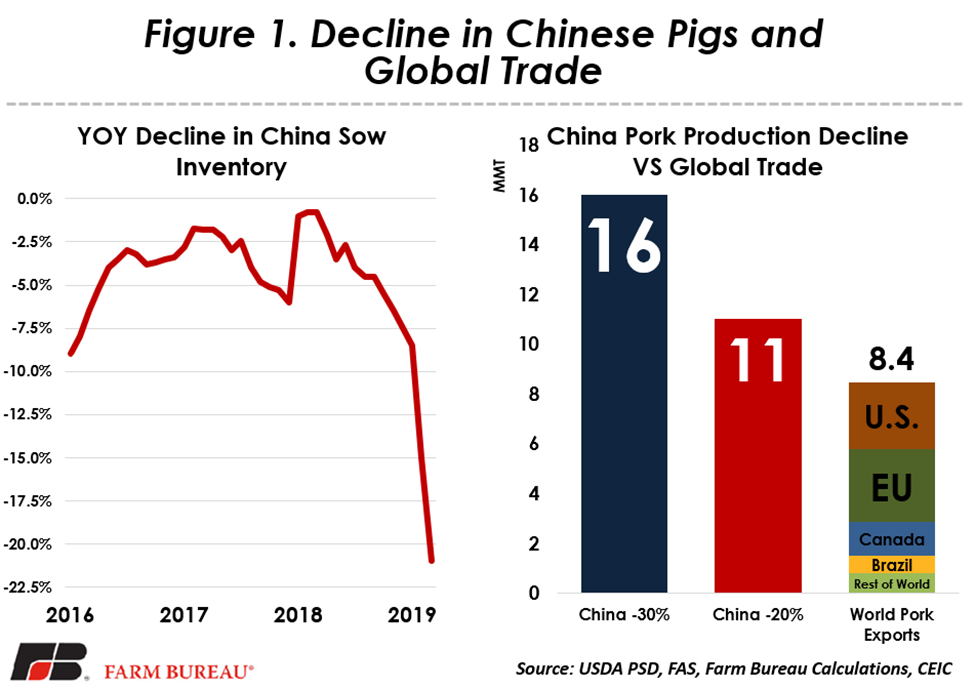

China’s herd numbers continued to fall from February, with the total pig herd down 1% and the sow herd falling 2.3% from the previous month. It should be noted that there is disagreement between different areas of China’s government, with the National Bureau of Statistics reporting much lower declines of 10% for the total herd and 11% for the sow herd from last year. For what it’s worth, most analysts suspect all of these numbers are underreported. Rabobank has projected that 2019 pork production in China will decline by 30%, dropping from 54 MMT in 2018 to 38 MMT this year. While at one point I may have thought that number was somewhat extreme, I now wouldn’t be incredibly surprised if this number came to pass, particularly with some analysts speculating even greater volumes of disruption.

To give some perspective, let’s take the 21% decrease in the breeding herd reported in March and extrapolate that to pork production (not an exact linear relationship, but a 20% decline in pork production certainly seems like a reasonable estimate given the rapid spread of the disease). A 20% decline in pork production in the country would roughly equal 11 MMT. In 2018, total pork exports for the entire world were just 8.4 MMT. A 30% reduction in Chinse pork production would be approximately 16 MMT, or about double the global pork trade. There is simply not enough excess pork in the world to supply the anticipated shortfall in production that China will experience. The major exporting countries may have some additional export capacity, but it is nowhere near enough to meet normal export demand as well as compensate for the Chinese shortage. The U.S. Meat Export Federation estimates that 2019 global trade could potentially be pushed to 11.7 MMT, but this 40% increase would not be enough to meet the world’s shortage.

The driving factors behind the extreme and rapid spread of the disease in China are the density of animals, the country’s industry structure and the fact that the animals have to be transported very long distances from farms to harvesting and processing facilities. While actual numbers on production by farm size and type don’t exactly exist for the country, one can break down Chinese hog farms into a few general buckets: approximately 20-30% of the animals are in very small, “backyard-style” farms; approximately 20-30% of the animals are in larger, more modern production facilities that often import European or U.S. knowledge and practices; and the remaining animals are on farms that are larger than the “backyard-style” farms, but still relatively smaller systems that lack the more sophisticated biosecurity measures of the larger farms. It should be noted that the larger, more biosecure facilities are by no means immune from ASF, as they too are being severely hurt by the disease.

The ultimate result of this disease is likely to be a restructuring of the pork industry in China, and we can expect to see an acceleration in the concentration of the industry that we have seen in recent years as the smaller farms will fail to recover. There are already many reports of farms choosing to not restock after culling from ASF, with MARA reporting as many as 80% of farms deciding not to restock. There are also many anecdotal reports of those who have decided to restock seeing their animals become infected again.

The disease has been detected in every single province in China. One particularly concerning province is the island of Hainan, as some hoped that the water between the island and the mainland would be a barrier to the disease. This is not the case, as last week six cases of ASF were reported on the island. You can be assured that Japan and Taiwan are taking that development very seriously, particularly as ASF-positive pig carcasses continue to wash up on Taiwan’s shore. Mongolia has seen a series of outbreaks that have decimated many of its animals. Also alarming is how quickly the disease spread through the country of Vietnam. It was first reported in the country on Feb. 19 and spread rapidly, crossing the border into Cambodia on March 22. It took the disease many years to work its way from Africa to Eastern Europe, and many years to work its way to China, where it spread throughout the country in less than eight months and crossed through Vietnam in approximately a month.

China Buys Pork, But…

China loves its pork, and the protein accounts for approximately 60% of meat consumption in the country. By far the largest producer and consumer of pork, China claims almost half of the world’s consumption. To give some perspective, the global annual pork trade is only equivalent to about two months of Chinese consumption.

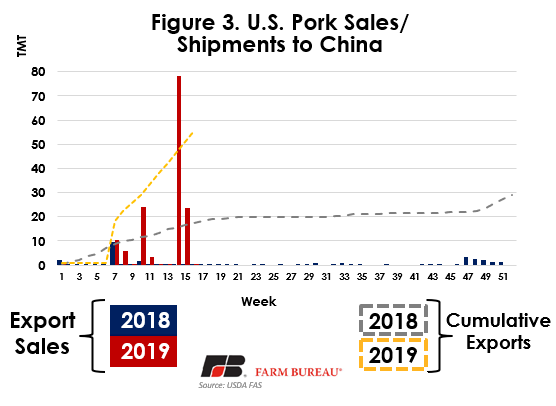

China is already increasing its pork imports, even bumping up purchases from the U.S. in spite of the average 62% tariff on the product. Since mid-February, China has made purchases of over 146,000 MT from the U.S., with an eyepopping 78,398 MT purchase made the week of April 5. It should always be noted that sales do not equal export shipments, and they could still be cancelled (a frequent occurrence). However, even if some of these sales are cancelled, cumulative exports this year are already trending significantly above 2018 and seem poised to continue to do so. As of April 18, outstanding sales for 2019 (product that has been sold but not yet shipped) measured 110,626 MT.

It is also important to not get too far ahead of ourselves in terms of these large disparities between China’s expected production and its consumption needs. China has quite a large amount of pork in stocks to draw from. While the country is eating through them quickly, we should not expect to see an extreme spike in global trade to come until later this year or even potentially early 2020. Even then, the country still bans imports of pork containing ractopamine, so for now at least, pork in the U.S. will have to come from the approved plants that produce this specific product.

Potential Impacts for Other Animal Proteins

While Chinese citizens will still demand pork, end consumers are expected to substitute other animal proteins for pork in their consumption habits. This may be driven by a distrust in the safety of pork (even though ASF does not impact humans) as well as by the resulting increase in the price of pork. Globally, poultry stands to be a big beneficiary of the ASF outbreak in China and the resulting shortages of protein on the global market. This is partially because chicken producers can respond more quickly and ramp up production faster than producers of beef or pork, chicken’s primary competition in the protein market. It typically will take six weeks to grow a bird to market weight, compared with four-five months for pork and 18 months for beef. It is also because chicken may be less of a jump for some consumers in terms of a substitution. In addition, it is cheaper than pork, while beef is more expensive. This is the part of the article where I remind readers that U.S. chicken is currently shut out of the Chinese market, so unless the U.S. and China come to an understanding, U.S. chicken will benefit indirectly by backfilling in other markets. (While there are many reports of an impending understanding between the two countries, we won’t pretend to know what is ultimately going to be included.)

Beef is also expected to somewhat benefit from ASF in China, but likely not to the degree that poultry will. Any realization of benefits for beef will likely take some time to develop. Additionally, some Chinese consumers just don’t have the purchasing power to make a real switch to beef due to the differences in prices between the proteins. We also can’t forget another animal protein that typically does not get as much attention: aquaculture. In addition to eating more beef and poultry, Chinese consumers are expected to increase their consumption of seafood as well.

One animal protein that could experience a negative effect is dairy, although many wouldn’t expect ASF to influence the dairy at first glance. When pigs are weaned, their starter feed can contain up to 25% dried whey permeate (a non-fluid dairy product). Since China has the largest hog herd in the world, they also have the largest number of piglets, making them large consumers of dried permeate. With the drastic reduction in the sow herd in China, the large amount of dried permeate that Chinese piglets consume is expected to decline. This decline could be somewhat muted due to the fact that many of China’s culled animals were on “backyard-style” farms, which were likely not utilizing permeate in feed, but the larger modern farms have not been immune from the disease either and so the impact has the potential to be significant.

What About an Impact to U.S. Soybean Farmers?

U.S. soybean farmers have had a rough go of things with the commodity being the tip of the spear in trade retaliation from China. Before the trade dispute, more than one quarter of U.S. soybeans were being sent to China. China was importing the whole oilseed, using its domestic crushing industry to produce meal to feed to its large domestic hog herd. There was already speculation that Chinese hog producers were feeding a higher protein content (i.e., soybean meal) than was necessary, and with the trade war they had adjusted this downward. In recent weeks, there have been growing reports of an impending trade understanding being struck between the U.S. and China, and subsequent speculation on U.S. soybeans being purchased by China. Unfortunately, if this is the case, the reduced hog numbers in China will lead to a downturn in the feed demand.

USDA’s Foreign Agriculture Service staff in China are predicting Chinese demand for oilseed products to be stagnant, but not in decline. While I don’t fully agree with this assessment, there is something to be said for the impact to soybean demand not being as alarmist as some in the industry think. If one thinks back to the structure of the Chinese hog industry, it is likely that the majority of hogs in China are not in commercial production and not being fed a 100% commercial ration (The mid-sized and even to some extent smaller producers may be using some soybean meal, but not as much as the commercial farms are). So, while hog numbers would go down significantly, there may not be as significant a drop in in the quantity of soybean meal demanded. Additionally, meal accounts for approximately 80% of the bean, with the remaining 20% being oil (with some hull waste). China isn’t expected to decrease their food and industrial use of soybean oil anytime soon, so they will still demand soybeans for food processing (although palm oil can provide an economical substitute in food use for soybean oil). Additionally, China may not want their domestic crushing industry to get caught up in the ASF disaster that is already impacting their pork producers.

All of this is to say that the ASF situation in China, which will take years to get under control, continues to decimate the world’s largest hog herd and will have dramatic impacts on global meat trade.