Low Mississippi River Levels Again Jeopardize Farm Income

photo credit: Getty Images

Daniel Munch

Economist

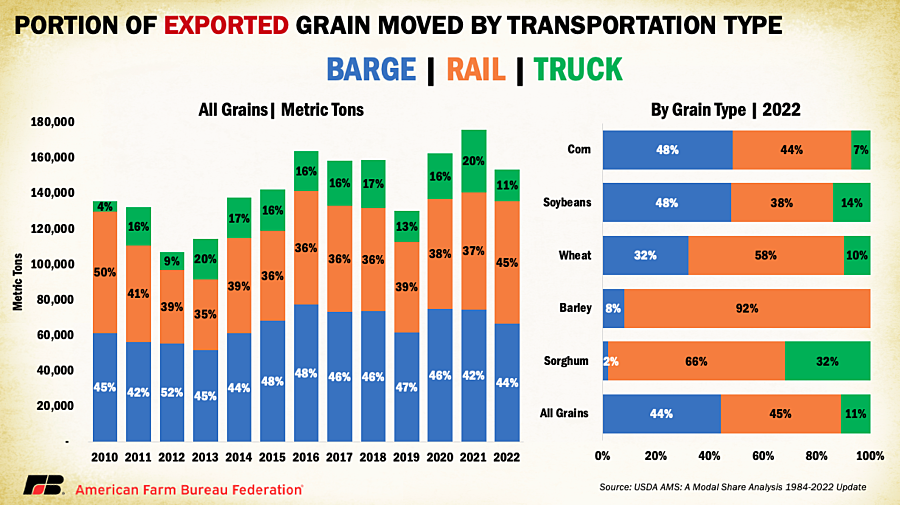

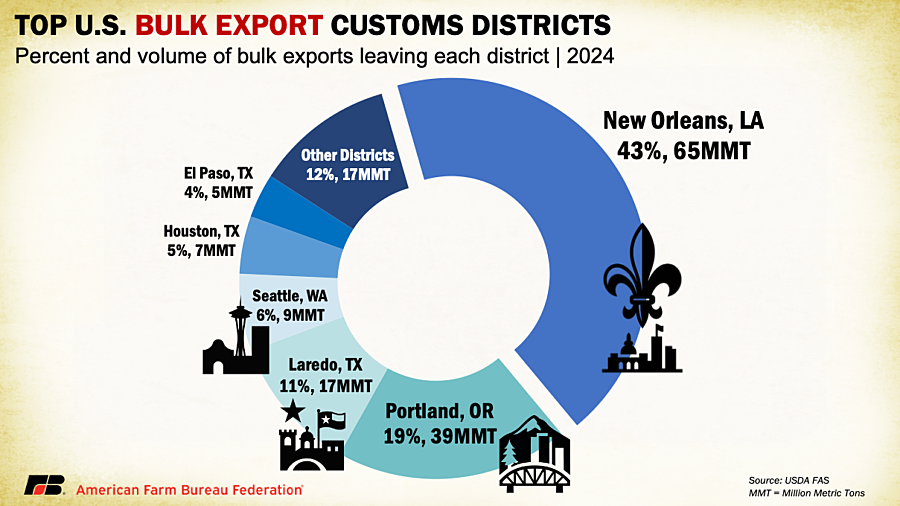

Close to half of all U.S. corn, soybeans and wheat exports move through the Mississippi River system, making it one of the most important export corridors in the world. Over the past five years, an average of 65 million metric tons of bulk agricultural product traveled by barge to terminals near New Orleans, where shipments were loaded onto ocean vessels bound for global customers. This inland waterway remains the most cost-effective way to connect Midwestern farms to foreign markets, ensuring U.S. agriculture can compete on price and reliability.

However, for the fourth consecutive year, historically low river levels are threatening that critical connection to global markets. Persistent drought has once again reduced the depth and width of the navigation channel, forcing barges to carry lighter loads, limiting tow sizes and pushing transportation costs higher. These conditions, arriving during the peak of harvest, are putting additional pressure on farmgate prices and raising concerns about the competitiveness of U.S. grain exports.

Why Barges on the Mississippi River?

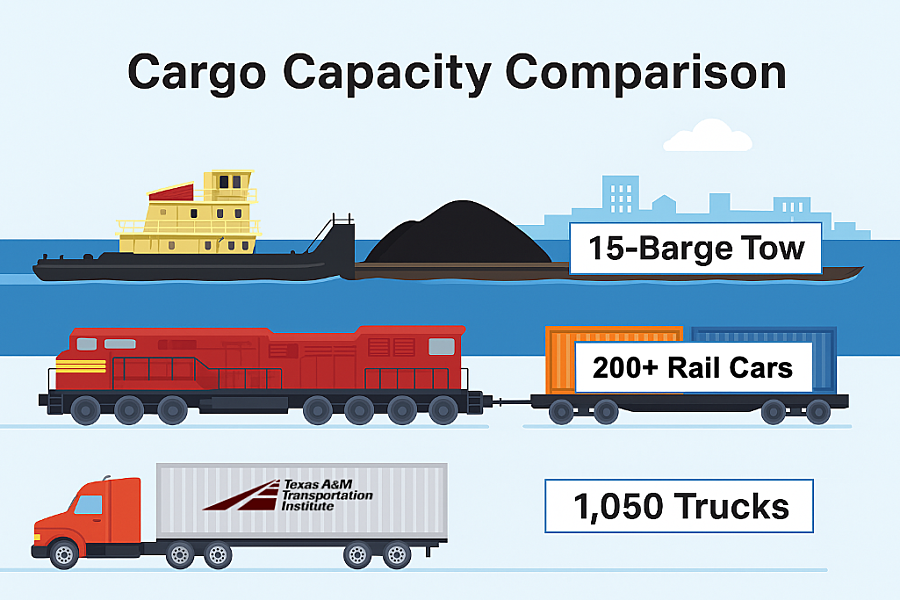

For decades, the Mississippi River has provided U.S. farmers with a decisive cost advantage in global markets. U.S. inland waterways save shippers an estimated $7 billion to $9 billion each year compared to rail or truck alternatives. A single barge can carry roughly 1,750 tons of grain, and a standard 15-barge tow (a common sight on the Mississippi) moves as much cargo as two 100-car-unit trains or about 1,000 semi-trucks. That scale, combined with lower fuel use and lower labor per ton, makes barge transport the most economical option for moving bulk commodities. When water levels are normal, this efficiency keeps delivered costs low, strengthens export bids at Gulf terminals and supports stronger local prices for farmers. But when the river runs shallow, that advantage quickly erodes and barges must carry lighter loads, requiring additional trips and increasing the per-ton cost of shipping grain.

That efficiency explains the importance of the river to reaching global markets. Nearly half of all corn and soybean exports (48%) are first moved by barge down the Mississippi system, underscoring how vital the river is to keeping those crops competitive. By contrast, wheat, barley and sorghum rely more on rail, with trucks making up only a small share of total export movement. This mix explains why disruptions on the river disproportionately effect corn and soybean farmers.

Current Mississippi River Conditions

As of Sept. 23, the Army Corps of Engineers reported the Mississippi River at St. Louis at just 1.27 feet, measured against the local “zero-stage” reference point that corresponds to 379 feet above sea level. That reading is more than 22 feet lower than at the end of July (a nearly 95% drop in less than two months) and about 90% below the average stage observed since early 2019. Farther south, the Memphis gauge has already fallen to –5.5 feet, meaning the river’s surface is five and a half feet below the gauge’s zero reference, and without significant rainfall is projected to near –8 feet by the end of the month.

In response to these declines, on Sept. 15, the U.S. Coast Guard imposed additional draft and tow size restrictions on the lower Mississippi River. Southbound traffic near Memphis is now limited to barges drawing no more than 10.5 feet of water (the draft, or how deep the barge sits in the river) and tows no wider than six barges. Northbound traffic faces even tighter limits, with barge drafts capped at 10 feet and tows restricted to four to six barges across and no more than seven barges long, depending on load size. Combined, this means more barges will be needed to move the same quantity of products and more boats will be needed to move smaller groups of barges, pressuring capacity.

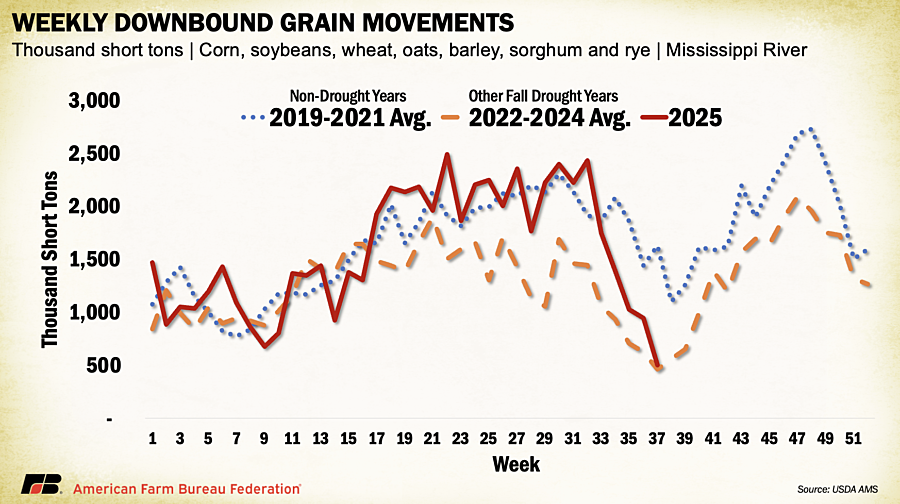

These restrictions have already led to steep declines in southbound grain traffic. USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, which tracks weekly barge movements of corn, soybeans, wheat, oats, barley, sorghum and rye, reported that in just over a month total southbound Mississippi River grain shipments fell from 2.4 million short tons to 502,000 — a 79% drop. Within that total, corn movements fell 72%, soybeans 89% and wheat 55%. Current volumes are well below the 2019–2021 average of 1.63 million short tons, a period with limited drought impacts. They are, however, slightly above the 2022–2024 average of 462,000 short tons, when drought severely constrained navigation. During the 2022 event, agricultural exports via Louisiana ports fell 3.9% (about $565 million) in the second half of the year, underscoring how quickly river problems translate into lost sales. Slower grain arrivals at Gulf terminals also risk ceding sales to competitors like Brazil and Argentina, whose exporters are quick to fill gaps when U.S. shipments are delayed.

Barge Rate Impacts

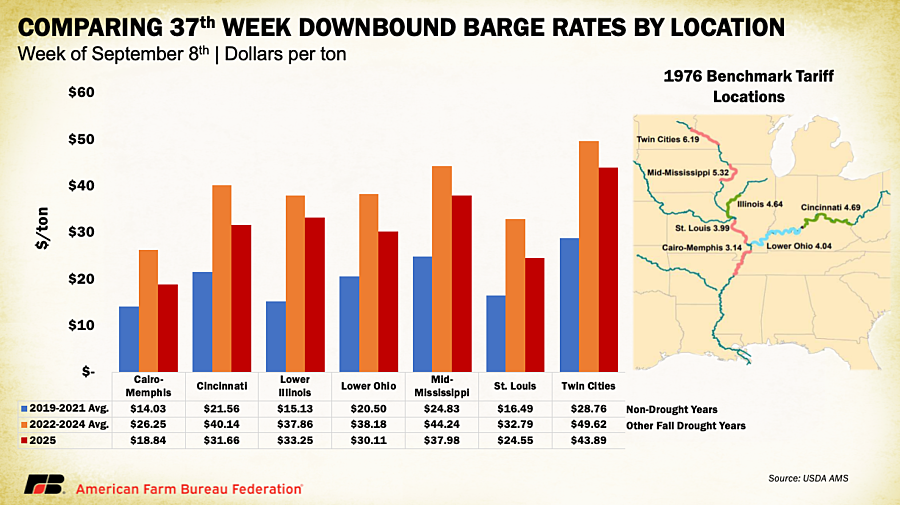

Traffic strains on the Mississippi have already pushed barge rates higher. USDA’s AMS tracks gulf-bound freight from seven points along the system: Twin Cities, Mid-Mississippi, Illinois River, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Lower Ohio and Cairo-Memphis.

Rates are quoted as a percent of a 1976 benchmark tariff that, while long deregulated, remains the industry’s standard reference. Each city has its own benchmark, ranging from $6.19 per ton in the Twin Cities to $3.14 in Cairo-Memphis. The true per-ton cost is the benchmark multiplied by the tariff percentage. For example, a 300% tariff for a St. Louis grain barge would equal 300% of the St. Louis benchmark rate of $3.99, or $11.97 per ton.

In the 37th week of 2025, per-ton barge rates remain well above long-term averages but have not yet reached the record levels of earlier drought years. For example, Cairo-Memphis shipments averaged $18.84 per ton this year compared to $14.03 in non-drought years and more than $26 during the 2022–2024 drought average. Similar patterns hold across other locations, with rates at Cincinnati, Mid-Mississippi and the Twin Cities all elevated relative to non-drought years but still lower than the peaks of recent drought episodes.

These elevated but not record-breaking levels suggest the system is already under strain, even before grain harvest reaches full force. If river stages continue to fall through October, rates are likely to climb closer to previous drought-year highs. For farmers, that means the potential for further basis weakening and even steeper discounts at river terminals. Basis is simply the difference between the futures price of a crop and the local cash price farmers receive. As barge costs climb, local buyers lower their bids to cover the higher expense. Which will ripple downstream and have effects on cash flow and competitiveness in export markets. In past years, this meant soybean basis along the river swung from slightly above futures to more than a dollar below, cutting directly into farm income.

Conclusion

The Mississippi River has long been one of the greatest cost advantages for American agriculture. New Orleans is the clearest example of this advantage, which handles 43% of all bulk agricultural exports and serves as the direct link between the Corn Belt and global buyers. This concentration makes the river system indispensable to U.S. trade, but also magnifies the risks when navigation is disrupted.

Elevated barge rates and weaker basis are cutting further into farm income just as the bulk of the harvest comes to market, while exporters face delays that give competitors room to step in. Keeping this system reliable will require continued dredging and infrastructure investment, but the simplest fix remains beyond anyone’s control: timely rainfall across the basin. Until that relief arrives, farmers and shippers will continue to navigate a river running low and the costly ripple effects of doing so.