Mexico’s Retaliation List Looks Familiar Because It Is

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: iStockPhoto

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Senior Economist

When the U.S. announced that from June 1 on, Canada, Mexico and the European Union would no longer be exempt from a new 25 percent tariff on steel and a new 10 percent tariff on aluminum, we knew retaliatory duties were coming. Within a few days of the U.S. announcement, all three trading partners had publicly released a list of U.S. products, many agricultural in nature, that would face additional tariffs. The Canadian and EU taxes go into effect July 1. Mexico’s taxes go into effect on July 5.

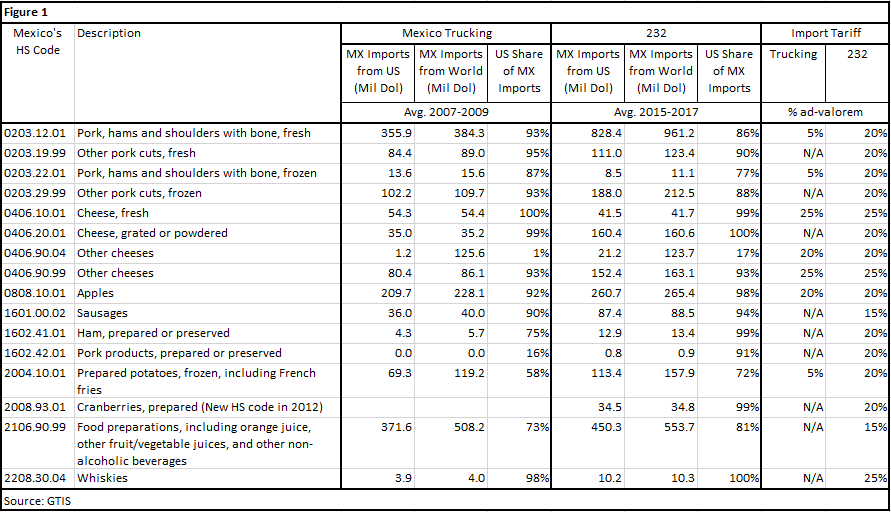

As analysts, the business community and policymakers have pored over the lists to see which products are in and which products are out. Mexico’s current retaliatory list includes 16 agricultural products; including pork hams and shoulders, various cheeses, apples, sausages, frozen potatoes, frozen cranberries, orange juice and whiskey. The current trade situation has prompted many to wonder out loud if we’ve seen anything like this before. In the case of Mexico, a ready example lies in the cross-border trucking dispute of 2009-2011. In this Market Intel, we compare the 2010 retaliatory list to the 2018 retaliatory list.

Background: Under the North American Free Trade Agreement, the United States and Mexico agreed to phase-out restrictions on cross-border passenger and cargo services. In 1995, however, the United States announced it would not lift restrictions on Mexican trucks. In 2001, a NAFTA dispute settlement panel found the U.S. restrictions to be in breach of its NAFTA obligations. After several years of negotiation, in 2007 Mexico agreed to cooperate in a joint demonstration program as a step toward full NAFTA implementation. However, the program was cancelled in 2009, prompting Mexico to retaliate against the U.S. Over the course of the dispute, Mexico followed what is known as a carousel approach, rotating different products on and off the retaliatory list. The first list, with 89 products, went into effect on March 19, 2009. The list was revised on August 18, 2010, by removing 16 of the previously named products and adding 26 more, bringing the total number of products on the second list to 99.

Mexico’s current retaliatory list includes 16 agricultural products. Over the last three years, the average annual U.S. exports of these products to Mexico totaled nearly $2.5 billion. The average U.S. market share for these products was 87 percent. Of those 16 ag products, seven were on the 2010 retaliation list. Of the seven products on both lists, the U.S. has experienced increases in both the value of exports and U.S. market share. In 2007-2009, before the trucking tariffs went into effect, the average annual U.S. exports of these products to Mexico totaled more than $784 million. By 2015-2017, U.S. exports of the same products exceeded $1.4 billion. The average U.S. market share for these products grew from 77 percent in 2007-2009 to 83 percent in 2015-2017. For six of the products, the retaliatory tariff is the same as it was during the last dispute. However, for three products--fresh hams, frozen hams and frozen potatoes--the 2018 proposed retaliatory tariffs are much higher, 20 percent instead of 5 percent.

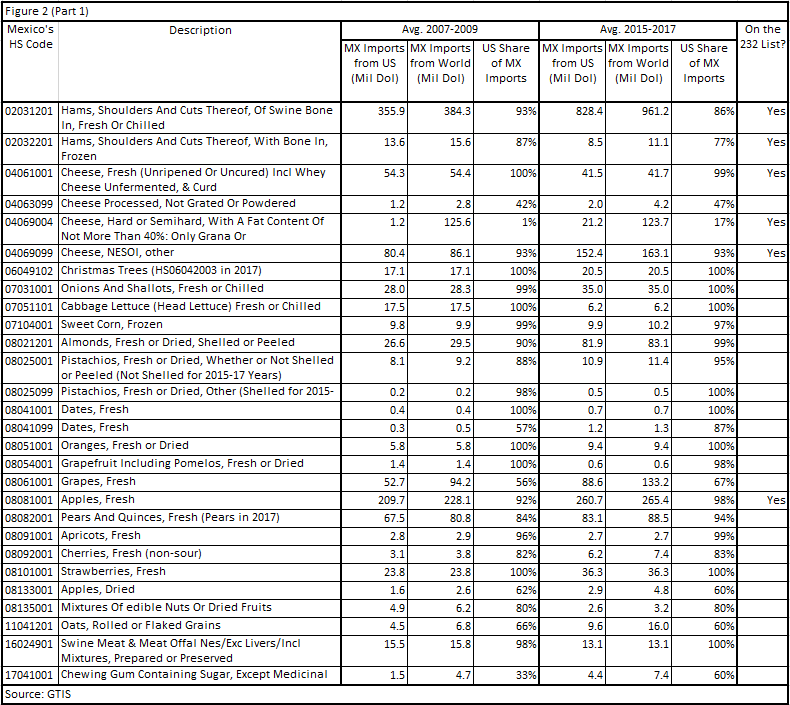

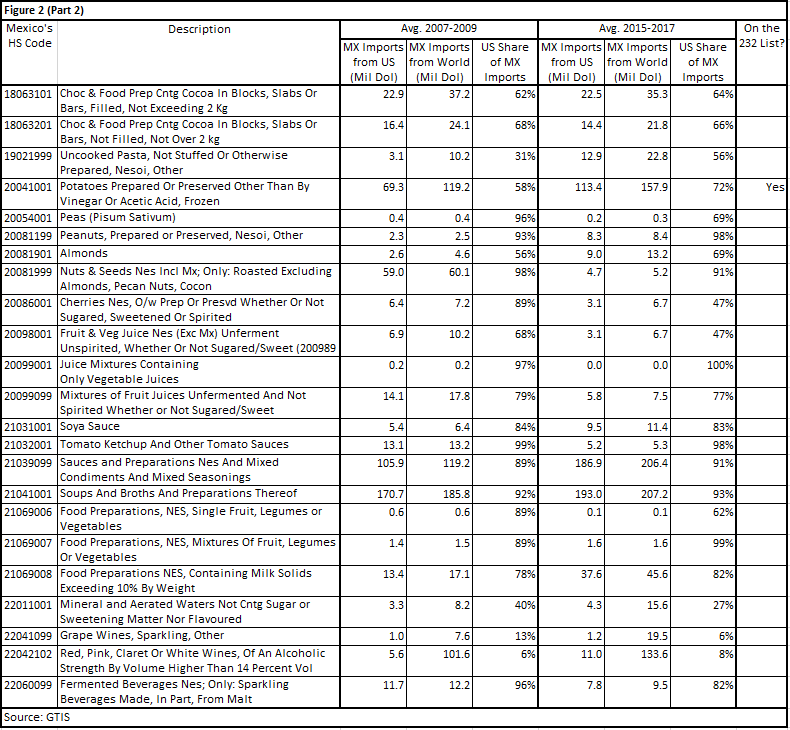

If the U.S. learned anything from the last trade dispute, it is that Mexico knows how to maximize the impact of a retaliatory tariff list. The U.S. agricultural industry should expect that the number of agricultural products on the list will both increase and change. In Figure 2, we see the agricultural products – more than 50 in total - that were on the 2010 list. We should not be surprised to see some of these products appear once again on a revised retaliatory list, especially those with a high export value and high U.S. market share.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL