New World Screwworm Moves Beyond Containment Threshold

TOPICS

screwworm

photo credit: Getty Images

Bernt Nelson

Economist

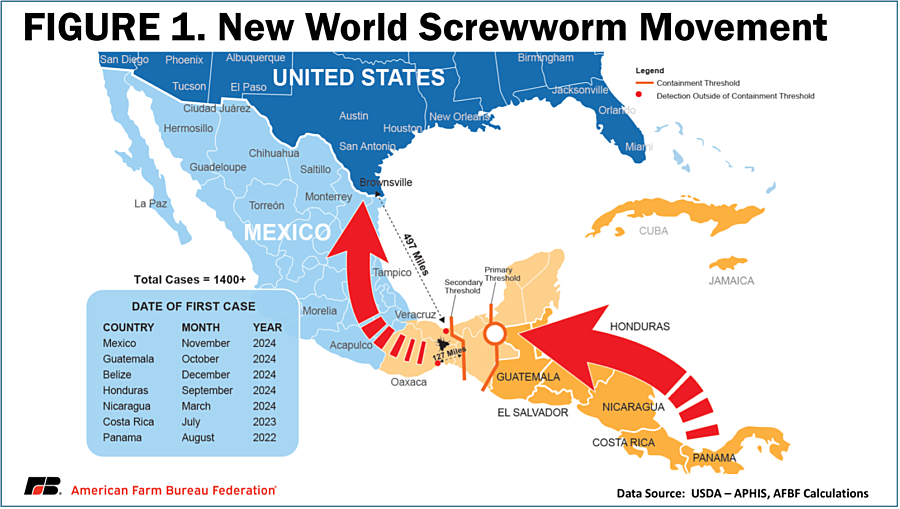

To protect the U.S. from a new threat posed by an old foe, the New World Screwworm (NWS), the U.S.-Mexico border was closed on May 11 to cattle, bison, and horses from Mexico. This pest was eradicated from the U.S. in 1966 and eliminated as far south as Panama by 2000. NWS began re-emerging above the biological barrier in Panama in 2022 and has continued moving north through Central America and Mexico. NWS is a serious health and economic threat that could cost the U.S. billions. This Market Intel analyzes the re-emergence of NWS and the danger it poses to animal health, human health and food security.

What is the New World Screwworm?

NWS is a fly endemic to Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and countries in South America. The pest has spread northward to Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Belize, El Salvador and, more recently, Mexico. The fly lays eggs on a warm-blooded animal, typically on or near a wound. When the eggs hatch, the larva feed on the surrounding flesh as they burrow into the wound, which is how the pest got its name. NWS can infest any warm-blooded animal including livestock, poultry, wildlife, domestic animals, and, though rarely, humans.

NWS is typically endemic to warmer climates. In fact, the larvae cannot survive temperatures below 46 degrees Fahrenheit. However, a cold climate doesn’t eliminate the threat. Livestock and wildlife movement can transfer NWS to the northern regions of the country in the summer months where they can find hosts and spread until temperatures cool off during fall and winter. NWS flies are able to travel as far as 12 miles to find suitable hosts. This pest does not discriminate among warm-blooded hosts, and wildlife such as deer, feral hogs, and even birds can quickly spread NWS. If left untreated, NWS infestations can be fatal. Animals can die of trauma, toxicity or other infections within two weeks.

New World Screwworm Treatment

As addressed earlier, NWS was eradicated as far south as Panama by 2000 when a biological barrier was established using the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). SIT is the release of mass-produced sterile male flies in strategic areas. The male flies mate with the wild females to produce unfertilized eggs. Since the female NWS flies only mate once, the wild population shrinks until the pest is eradicated. The only fly production facility in the world is in Panama.

While SIT is the only tool we have to eradicate NWS, there are options for treatment once NWS is detected. First, screwworm infestations must be reported to state and federal authorities. Treatment for NWS involves killing and removing the larvae from the infested wound. Nitenpyram is highly effective for killing and expelling NWS larvae quickly. Ivermectin has been successful in treating and even preventing NWS infestations. Screwworms can also be killed by dressing an infested wound with an anti-parasitic such as lindane or ronnel. All wounds must be dressed to promote healing and avoid reinfestation.

NWS is extremely difficult to eliminate and there have been some isolated incidents of re-emergence in the U.S. For example, NWS re-emerged in the Florida Keys in 2016. Officials reacted quickly by releasing sterile flies and by 2017 the pest was eradicated again. This is evidence of just how difficult NWS is to control.

Breaching Thresholds

When NWS was discovered in the Mexican state of Chiapas in November 2024, primary and secondary thresholds were established as breaking points for fly control. The Panama production facility had enough capacity (about 100 million flies per week) to release sterile flies inside the buffer zone between the primary and secondary threshold and push them back to the biological barrier in Panama.

Since November 2024, there have been over 1,400 detections of NWS in Mexico. On May 11, U.S Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins announced suspension of live animal imports from Mexico because NWS had been detected 127 miles outside of the secondary threshold in Oaxaca and Vera Cruz, Mexico. With the break in the secondary threshold, there is no longer enough sterile fly production capacity to keep NWS from moving further north (Figure 1).

Economic Threat to U.S.

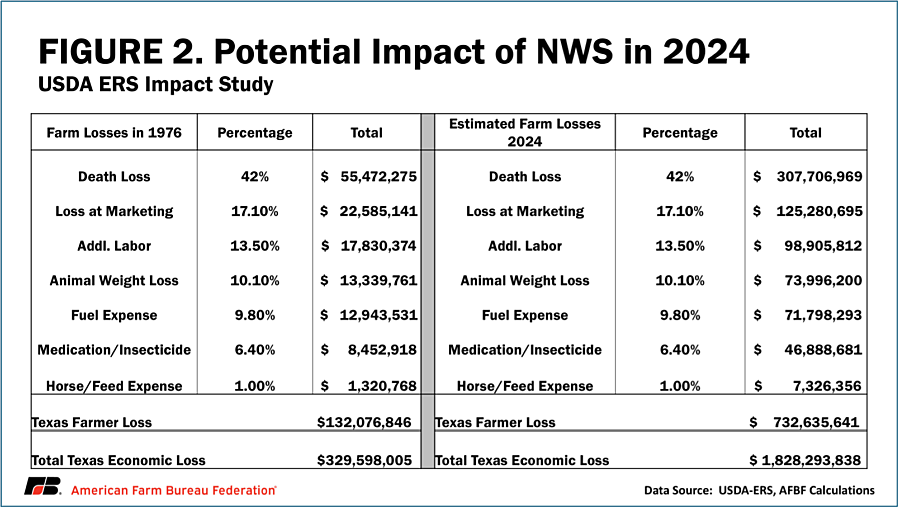

USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) conducted an impact analysis that used historical data to estimate the impacts of a screwworm outbreak in Texas. Texas is home to 12.5 million head, or about 14% of all U.S. cattle. This is two times more than runners up Nebraska and more 67% more than all other U.S./Mexico border states combined. The study included costs incurred from the isolated 1976 outbreak, adjusted them for inflation, and applied them to today’s cattle inventory in Texas (Figure 2.). According to this study, the annual economic cost is estimated to be $1.9 billion. Of note: there were more people working on farms in 1976 than there are now. Managing an outbreak takes considerably more labor to care for and check animals for signs of NWS. This would come at a time when farmers and ranchers are already struggling

to find people to help carry out routine daily tasks.

On the farm level, the presence of NWS adds a considerable amount of cost to day-to-day operation, with death of infected cattle the single greatest expense. When an infestation is found on a farm or ranch, a veterinarian must be called, and medication is prescribed and administered. This adds cost for time, labor and treatment. Treated animals often lose weight, which results in a less valuable animal or even a mother cow that is unable to feed her calf. When this happens it takes additional time, labor and supplies to care for both the mother cow and her calf. Many farmers and ranchers inspect and work cattle on horseback, which means more horses are needed, adding to feed costs, not to mention the horses’ susceptibility to NWS infestation.

Summary and Conclusions

NWS ranks among the top animal health and food security concerns in 2025. The pest has broken through the containment threshold less than 500 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border and the only weapon to stop it is no longer enough. It takes time to build new facilities that can produce enough flies to fight against this adversary. Even then, SIT is not a quick fix. Reducing the wild NWS population and pushing it back to the biological barrier is a slow process that could take years or even decades. ERS estimated the cost of an outbreak to be $1.9 billion annually for Texas alone. Imagine adding this to the 10 other U.S. states in Figure 1. Time is of the essence.