Stop the RIN-sanity

TOPICS

Soybeans

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Philip Gerlach

John Newton, Ph.D.

Vice President of Public Policy and Economic Analysis

The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program provides the regulatory framework for establishing the minimum volume of renewable fuels that are to be blended into the U.S. transportation fuel supply. The RFS was designed to improve environmental quality by reducing greenhouse gas emissions; increase energy security by reducing dependence on imported oil; and expand and promote the production of renewable fuels such as corn-based ethanol or soybean-based biodiesel. The key compliance mechanism that the RFS uses to ensure that obligated parties, i.e. refiners and blenders, meet their annual renewable volume obligation are Renewable Identification Numbers. RINs are generated based on the production of biofuels and fluctuate in value based on market supply and demand.

In recent months a number of modifications have been proposed to substantially alter the RFS program. The proposals include RIN multipliers, capping the value of RINs and not retiring RINs upon export. And while recent reports suggest changes to the nation’s biofuels policy are on hold, any future efforts designed to artificially change RIN supply and demand would erode the integrity of the RFS program and weaken the principal RFS compliance instrument. Given that the price of RINs has been a key element of the policy debates over modifications to the RFS, today’s Market Intel provides an overview of RIN generation and prices.

RIN Generation

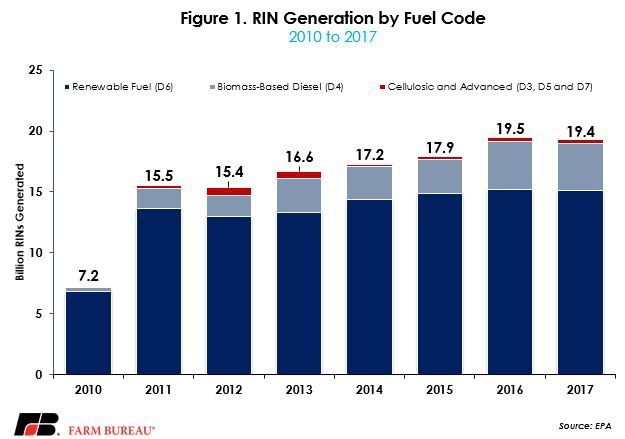

To protect the integrity of and ensure compliance with the RFS, whenever a gallon of biofuel is produced, it is assigned a RIN. There are several fuel categories that have corresponding RINs. For example, D6 RINs are associated with conventional ethanol biofuel and D4 RINs are associated with biomass-based diesel – the two most widely produced types of biofuel. These two RIN fuel codes represent on average 98 percent of all RIN generations since 2010.

Other fuel categories, such as D5 RINs, are associated with advanced biofuels and track closely with the value of biomass-based biodiesel RINs. D3 and D7 RINs are associated with cellulosic biofuel and cellulosic diesel, respectively. Combined, these three RIN categories represent less than 2 percent of RIN generation since 2010. RINs with higher greenhouse gas savings, such as advanced biofuels or cellulosic fuels, are generally higher valued as they can be used to backfill other volume requirements. Figure 1 highlights RIN generation by fuel code.

After being generated, the RIN accompanies the gallon of biofuel through the supply chain, and once an obligated party blends the biofuel into the transportation fuel supply it can claim the RIN. The obligated party can then retire the RIN to the Environmental Protection Agency to demonstrate compliance with the RFS or sell it on the open market.

RINs do not expire immediately and can cross compliance years. When excess blending occurs, the RINs can be banked and used for compliance during the following compliance year ending March 31. Up to 20 percent of the prior year’s volume obligation can be met with these banked RINs. RINs outside of the compliance years are retired and can no longer be used for satisfying RFS volume obligations.

Value of RINs

Like any other asset or commodity, the value of RINs fluctuates based on supply and demand. For parties that have exceeded their blending requirement, i.e. by blending higher grades of ethanol such as E-15, their excess RINs can be sold to others along the supply chain, such as parties that have not blended sufficient volumes to meet their RFS obligation. Parties buying RINs can then use the purchased RINs to demonstrate compliance without actually blending their obligated volumes.

When the RIN market is tight and prices are higher, some along the supply chain have claimed that the costs of compliance can be higher for obligated parties not meeting their volume requirements – hence the proposals designed to lower RIN prices without increasing biofuel production. However, the EPA evaluated the impact of high RIN prices on refiners and concluded that refiners are generally able to recover the cost of RINs in the prices they receive for their refined products. Therefore, higher RIN prices do not necessarily increase compliance costs.

For companies exceeding their blending requirements, surplus RINs can represent an additional income stream for the business if they are traded along the supply chain. Importantly, for obligated parties meeting or exceeding their volume requirements, the RFS does not impose any additional costs of compliance.

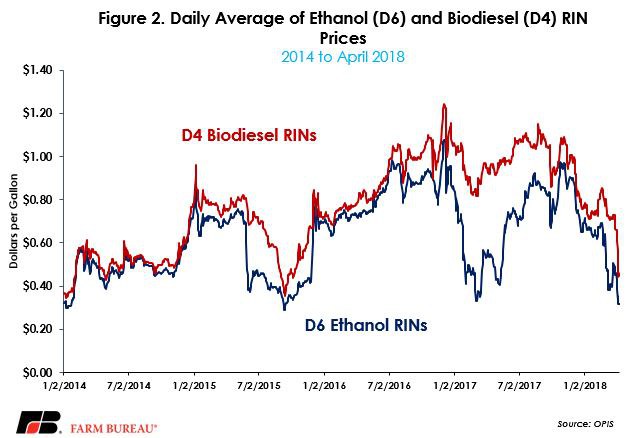

Prior to 2013, as the E-10 blend wall was being reached, the value of D6 RINs mostly remained below 20 cents per gallon. However, since 2014, the value of D6 ethanol RINs has ranged from a low near 30 cents per gallon to a high over $1.00 per gallon and has averaged just over 60 cents per gallon, Figure 2. D4 biodiesel RINs have ranged from a low also near 30 cents per gallon to more than $1.20 per gallon and has averaged approximately 80 cents per gallon. Figure 2 provides the daily average price of D4 and D6 RINs since 2014.

Summary

The RFS has faced political headwinds in recent months. First, the administration has openly discussed modifications to the RFS that would undermine RINs, the key compliance tool underpinning the RFS. Second, the Environmental Protection Agency has granted “hardship” waivers allowing noncompliance with U.S. biofuels regulations -- a waiver historically reserved for smaller obligated parties. One such waiver was for Andeavor, one of the largest refineries in the U.S. This creates a slippery slope, and just last week Exxon Mobil Corp and Chevron Corp also sought “small refinery” waivers from the RFS. Third, some retailers along the supply chain, i.e. Love's and Pilot Flying J, have made public their plans to back off their blending of biodiesel in some markets due to recent reductions in RINs. Lower RIN prices reduce the incentive to blend biofuels because purchased RINs are more cost-competitive with blending.

Combined, the role of RINs as the mechanism to ensure compliance with the RFS is facing increasing uncertainty. As a direct result, and as highlighted in Figure 2, RINs are approaching their lowest prices since 2013. Importantly, if the policy goal were reduced RIN prices, a waiver providing the ability to sell higher blends of ethanol year-round would increase the supply of both biofuels and RINs. By blending higher grades of ethanol more ethanol would need to be produced, and as a result the supply of RINs available for trade would increase. The President recently signaled year-round sales of E-15 could be on the horizon. The market response to additional RINs would be lower RIN prices and as a result lower cost of compliance for those not meeting their volume obligations. Such a waiver would not undermine the RFS and would increase environmental quality and energy security and would expand the production of renewable fuels – helping to support the increasingly lagging agricultural economy.

The RFS was designed to promote energy independence and the production of renewable fuels. Obligated parties and producers of biofuels have successfully grown the biofuels industry to nearly 20 billion gallons of production per year – in line with the proposed volume obligations of the RFS. Due to the development of the biofuels market, nearly 40 percent of U.S. corn production and 30 percent of soybean oil production each year is used to produce ethanol and biodiesel, respectively.

Without the RFS, and importantly RINs, the continued development and integrity of this key renewable energy market would be at risk. At a time when farm income is at a 12-year low, and trade barriers are potentially mounting for U.S.-produced grains and oilseeds, now is not the time to further devastate the farm economy by rolling back the RFS. It’s time to stop the RIN-sanity.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL