Strong Start, Fragile Future: U.S. Dairy’s Trade Balancing Act

photo credit: Utah Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Trade is a hot topic with a lot of uncertainty. Trade policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., will impact farmers and ranchers in the countryside. This Market Intel is part of a series exploring agricultural trade, including the potential impacts of trade policy changes.

Between January and April of this year, the United States imported $78.2 billion worth of agricultural products — the highest value on record. Over the same period, U.S. agricultural exports totaled just $58.5 billion, resulting in a record-setting agricultural trade deficit of nearly $20 billion in the first four months alone. Despite this dim outlook, one bright spot stands out: dairy. U.S. dairy exports exceeded $3 billion through April, marking a new record and outpacing dairy imports by more than $1 billion ($3 billion vs. $1.9 billion). Today’s Market Intel underscores both the importance of foreign market access to dairy farm profitability, the potential for market expansion from the current trade negotiating dynamics, and the continued vulnerability of the sector to volatile and unresolved trade disputes and barriers, despite a strong start to the year.

Where we Export Dairy

In 2024 the U.S. exported $8.2 billion in dairy products to 114 countries and the European Union, representing close to 5% of total ag exports by value. Despite this broad reach, just 10 markets accounted for 74% of total export value, and over half (51%) of all U.S. agricultural exports were concentrated in only three countries: Mexico, Canada and China — all currently at the center of ongoing trade tensions. Mexico has been the top destination for U.S. dairy products since surpassing Canada in 2003, purchasing nearly one-third of all U.S. dairy exports in 2024. China, a stable third-place market since 2009, briefly overtook Canada in both 2013 and 2014.

What Dairy We Export

Fluid milk and cream products are challenging to trade internationally due to their high perishability and water content, which make transportation costly relative to its market value. As a result, the bulk of U.S. dairy exports are in manufactured products with longer shelf lives and greater shipping efficiency.

In 2024, cheese led the way, with the U.S. exporting over $2.4 billion worth (508,791 metric tons), accounting for nearly 30% of total dairy export value. Nonfat dry milk — produced by removing most of the fat and water from fluid milk — ranked second, totaling over $2 billion in export value (25%) and topping the volume list at 741,791 metric tons. This versatile product is used in reconstituted milk, infant formula, dairy, bakery and confectionery items, and occasionally as animal feed or calf milk replacer.

Rounding out the top three was the “other dairy products” category, which includes powdered ingredients like lactose and milk protein concentrates. This category contributed $1.9 billion in export value across 660,535 metric tons. The U.S. also exported smaller but still significant volumes of whey, butter, ice cream and yoghurt.

The Importance of Foreign Markets

U.S. dairy farmers are the cream of the crop — pun intended. Only Israel surpasses the U.S. in per-cow milk production, and it does so on a fraction of the scale. Israel produces just over 4 billion pounds of milk annually, while the U.S. produced more than 226 billion in 2024. That means not only are U.S. cows incredibly productive, but they’re doing it in one of the largest and most sophisticated dairy systems in the world.

In 1924, the average U.S. cow produced 4,167 pounds of milk per year. Today, that number has climbed to 24,178 pounds, a nearly six-fold increase, thanks to decades of improvements in animal nutrition, genetics, health care and management. Total milk production has jumped 35% in just the last 25 years, from 167 billion pounds to 226 billion pounds.

While domestic demand for cheese, butter and other manufactured dairy products continues to grow, fluid milk consumption has experienced a long-term decline driven largely by changes in habits, reduced cereal consumption and broader beverage competition. Between 1970 and 2019, average fluid milk intake fell from nearly 1 cup per person per day to less than half a cup. That said, recent product innovations, such as ultra-high temperature shelf-stable milk, high-protein and lactose-free options and enhanced branding, may be helping to slow that decline, with some signs of modest gains in select market segments.

Still, with production efficiency continuing to rise and per capita fluid milk consumption unlikely to return to historic highs, it’s clear that the U.S. dairy industry must continue to look beyond our borders to stay competitive and profitable. That’s why exports are not just a bonus — they’re essential.

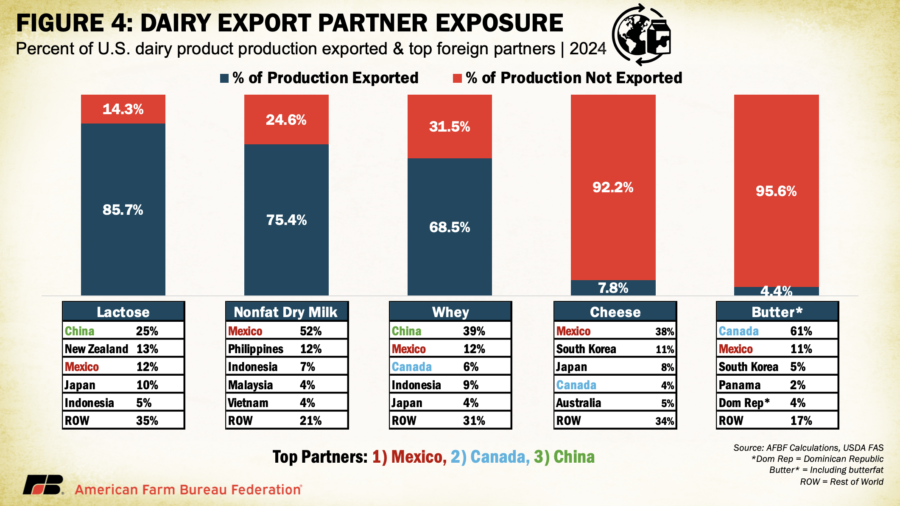

In fact, 16% of all milk production in the U.S. ends up being exported. This value varies greatly by product and destination. Though our primary dairy export product, only about 8% of our cheese production was exported in 2024 (compared to 5.5% in 2020). A much larger percent of powdered dairy products is reliant on exports markets, with 86% of lactose production, over 75% of nonfat dry milk production and nearly 70% of whey production being sold overseas.

This imbalance reflects how different products fit into global food systems. Powdered dairy products like nonfat dry milk, whey and lactose are not only in high demand globally — they’re also coproducts of processing the dairy goods Americans consume every day. When U.S. consumers buy cheese, for example, processors are left with large volumes of whey, and lactose is often separated from that stream. By selling these ingredients abroad, rather than letting them go to waste, processors create value that helps offset the cost of producing everyday dairy staples for U.S. consumers. China, the largest buyer of both U.S. lactose and whey, uses them primarily in swine feed to support its massive pork industry. Much like China’s demand for U.S. chicken feet supports U.S. poultry processors by creating value from parts Americans don’t typically consume, demand for dairy coproducts overseas helps U.S. dairy plants run more efficiently. In contrast, most of the fluid milk, cheese, butter and ice cream produced in the U.S. is consumed domestically. Exporting these coproducts is not just smart trade — it’s essential to making the whole dairy supply chain more sustainable and economically viable for farmers, processors and consumers.

This high level of export exposure also leaves U.S. dairy vulnerable to shifts in trade policy particularly as its top markets, including Mexico, Canada and China, have been subject to recent tariff actions or trade tensions under evolving U.S. trade strategies.

Let’s Get Country Specific

Understanding where and why trade barriers exist is key to grasping the risks facing U.S. dairy producers. Each of our top markets comes with its own mix of political, economic and regulatory challenges — and when around one in six gallons of U.S. milk is destined for foreign buyers, even small disruptions abroad can ripple back to the farm gate.

Mexico

Thanks to duty-free access under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and close geographic proximity, trade flows with Mexico have remained strong. USMCA, which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement in 2020, is the primary trade agreement governing agricultural commerce among the U.S., Mexico and Canada — and includes key provisions aimed at preserving market access for U.S. dairy. But even our most reliable partners aren’t immune to trade volatility. In early 2025, the Trump administration imposed broad 25% tariffs on most Mexican imports under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), citing national security concerns. While many USMCA-compliant goods, including most agricultural products, were later granted exemptions, the move triggered diplomatic backlash and threats of retaliation from Mexico. Though dairy has largely remained exempt, past experience has shown that it’s often among the first sectors hit when trade tensions escalate, making even strong export markets a potential risk for U.S. producers. That makes preserving existing trade flows and swiftly resuming full USMCA access for bilateral trade essential.

Canada

Despite being the second-largest buyer of U.S. dairy, Canada keeps its market tightly protected through a supply management system, which controls how much milk Canadian farmers can produce and imposes steep tariffs, sometimes over 300%, on imports that exceed set quotas.

When USMCA was signed, it included provisions to modestly expand U.S. dairy access. But Canada’s implementation has drawn sharp criticism. Instead of giving a wide range of businesses — like retailers, foodservice companies and distributors — the right to import U.S. dairy under the new quota system, Canada gave most of those licenses to its own dairy processors. Because these processors compete with U.S. products, they have little reason to actually use the licenses to bring in American dairy. The result is that the quotas technically exist, but much of the promised market access never materializes.

Canada had also used pricing categories called Class 6 and Class 7 to sell milk ingredients like skim milk powder at artificially low prices, undercutting U.S. exports both at home and abroad. Although USMCA required Canada to eliminate those milk classes and imposed export disciplines on various milk protein products to limit trade distortions, Canada introduced new pricing mechanisms for similar milk protein products that have a comparable effect — flooding international markets and displacing U.S. product. As a result, U.S. processors have been forced to adjust production and search for alternative products that fall outside the scope of these export restrictions.

Tensions deepened in early 2025 when the Trump administration imposed sweeping 25% tariffs on imports from Canada under the same IEEPA provisions used against Mexican imports. While most Canadian agricultural exports, including dairy, remain exempt under USMCA, Canadian officials have imposed countermeasures on a range of U.S. exports, including some dairy. Canada more recently introduced an exemption process that has significantly mitigated the impact of that retaliation, but the tariffs remain on the books.

Canada’s case underscores a hard truth: trade agreements alone don’t guarantee real market access. Domestic protectionism and political flare-ups can easily undercut what’s promised on paper. As long as Canada continues to evade its USMCA commitments, meaningful progress on dairy trade will remain limited, which is why productive negotiations – not stalemates – are essential to tackling those challenges.

China

China remains a vital yet volatile market for U.S. dairy exports, particularly for coproducts like whey and lactose used in livestock feed and food processing. However, recent trade tensions have significantly impacted this relationship.

In early 2025, the U.S. imposed 20% tariffs on Chinese goods, prompting China to retaliate with a 10% tariff on certain U.S. dairy products. Tariff tensions escalated further in April with the launch of U.S. reciprocal tariffs with China matching U.S. increases in tariffs to 34%, then 84%, and eventually 125% on all U.S. goods. These measures made U.S. dairy products significantly more expensive in the Chinese market, reducing their competitiveness against products from countries like New Zealand – which benefits from a free trade agreement with China – and the European Union.

However, in May 2025, the U.S. and China agreed to a 90-day tariff reduction, lowering China's additional retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods to 10% - 20% and the U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods to 30%. This temporary and partial reprieve offers a window for U.S. dairy exporters to work to regain footing in the Chinese market.

The U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) has emphasized the need for stable trade relations, noting that previous retaliatory tariffs resulted in an estimated $2.6 billion loss in U.S. dairy farm revenues from 2019 to 2021.

While China’s demand for dairy remains strong, this tariff volatility highlights the risks for American agriculture of the politically sensitive U.S.-China relationship.

European Union (EU)

U.S. dairy products face steep tariffs and excessively burdensome sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures in the EU. Whether on somatic cell counts or the use of antimicrobial tools, EU policies increasingly aim to dictate farming practices to the world, imposing an outsized burden on trading partners exporting to the EU.

Another significant point of contention is the EU's abuse of geographical indications (GIs) to restrict the use of common cheese names like "parmesan" and "feta" to products made in specific regions of Europe. These terms are generic, and the EU's policies unfairly threaten U.S. market access, not only within the EU but also in countries where the EU has secured GI protections that block the use of generic names through trade agreements.

In April 2025, trade tensions escalated when the U.S. imposed a 10% tariff on all EU imports. The EU responded with a proposed package of 25% retaliatory tariffs on $23.8 billion (€21 billion) worth of U.S. goods, including agricultural products. However, dairy products were notably excluded from the final list, following lobbying from major EU dairy-exporting countries concerned about potential U.S. countermeasures.

Despite this temporary reprieve, the EU's protectionist policies and the ongoing disputes over GIs continue to pose significant challenges for U.S. dairy exporters, driving a trans-Atlantic dairy trade deficit of nearly $3 billion.

India

India remains one of the most closed and politically sensitive dairy markets in the world. With over 80 million dairy farmers — many of them smallholders owning just two to five cows — the sector plays a vital role in rural livelihoods, nutrition and economic stability. Limited government reforms, persistent regulatory hurdles and broader challenges to business development have hindered industrialization. As a result, dairy remains one of the most heavily protected industries in the country.

U.S. dairy products face high tariffs, some as high as 60%, as well as persistent nontariff barriers. Chief among these is India’s requirement that imported dairy products must come from animals never fed animal-derived ingredients. While India cites religious and cultural reasons for this restriction, it has rejected multiple U.S. proposals designed to respect those beliefs while facilitating market access. The U.S. maintains that its milk supply chain can meet India’s stated requirements and that there is diversity in dietary practices across the Indian population. These tariff and certification rules continue to serve as effective barriers to U.S. dairy exports.

Despite over two decades of negotiation, little progress has been made. In 2024 and 2025, the U.S. and India resolved some longstanding WTO disputes and lifted certain retaliatory tariffs, but dairy access and other challenging topics were not part of the deal. India has continued to resist dairy in bilateral trade talks, signaling that it is devoted to keeping structural barriers in place.

For U.S. exporters, India represents a massive untapped market, but one where trade policy is tightly bound to domestic politics, food security, and protectionism. Overcoming those entrenched dynamics will take creative, pragmatic approaches to facilitating trade.

Emerging Markets: Southeast Asia and Beyond

Several fast-growing dairy importers including Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam represent major growth opportunities for U.S. dairy. These countries have rising consumer demand, expanding middle classes and limited domestic milk production.

Overall non-tariff barriers in Southeast Asia are relatively limited. However, one key limiting issue is Indonesia’s facility registration process. In Indonesia, each U.S. dairy processing plant must undergo an extensive approval process before any shipments can begin. This process can take three years and involves duplicative documentation, unclear criteria and little transparency. These delays have cost U.S. exporters real market share, as competing suppliers from countries with faster or pre-approved access fill the gap.

While the U.S. has made progress in resolving the impediment that facility registration can pose in some markets, for example, reaching a bilateral agreement with Costa Rica in 2025 to streamline plant approvals, other countries still maintain slow, opaque or inconsistent registration systems. These processes operate as de facto trade barriers, restricting access in a more subtle manner than tariffs. The ongoing U.S. reciprocal trade negotiations with multiple trading partners offer an excellent opportunity to tackle these types of barriers.

Conclusion: Trade Matters and So Does Vigilance

Dairy’s record-setting export performance in early 2025 is a testament to U.S. farmers’ productivity and the global appetite for high-quality American dairy products. But this success story is not guaranteed. As this Market Intel has shown, even our most established markets (Mexico, Canada and China) face evolving policy dynamics and trade pressures that introduce risk. At the same time, promising destinations like India and the EU remain challenging due to structural protectionism and non-transparent regulatory systems that limit access.

These realities make it all the more important for U.S. trade negotiations to deliver meaningful outcomes, ones that expand market access, ensure fair treatment and create lasting opportunities for U.S. dairy. For U.S. dairy farmers and processors, exports are not optional — they’re essential to keeping the supply chain viable and competitive. But tapping into global markets requires more than shipping containers and sales contracts. It demands persistent trade engagement, enforceable agreements and a long-term strategy to lower barriers and defend hard-won gains. With the right trade policies, dairy can continue to shine as one of agriculture’s global success stories.