U.S.-Grown First: Strengthening Federal Food Purchasing

photo credit: AFBF

Daniel Munch

Economist

Farmers and ranchers face rising costs, weak prices and uneven global competition that threaten their livelihoods. At the same time, policy decisions in Washington can increase market access, spur demand and ensure fair competition. This new Market Intel series will examine six priority policy areas - trade, biofuels, whole milk in schools, interstate commerce, transparent input markets and prioritizing U.S.-grown produce - and how each can help strengthen the farm economy and rural communities.

For nearly a century, federal food purchasing and nutrition programs have played a dual role, feeding Americans while providing dependable markets for U.S. farmers and ranchers. These policies, from the earliest Buy American statutes of the 1930s to modern federal procurement rules, reflect a long-standing belief that public dollars should reinforce U.S.-grown food production.

Yet, while federal purchasing overwhelmingly favors U.S.-grown products, enforcement and reporting gaps remain. Inconsistent tracking of Buy American exceptions in school meal programs and limited transparency around sourcing reduce the potential impact of these initiatives for American producers.

This Market Intel reviews the history and structure of domestic preference policies in federal food procurement, their impact on farm demand, and where opportunities remain to strengthen oversight and expand the use of U.S.-grown products across institutional nutrition programs.

Historical Roots of ‘Buy American’ Policy

Federal preference for U.S.-grown foods dates back nearly a century and was driven by economic, food security and national defense priorities. The Buy American Act of 1933 first required federal agencies to purchase domestic goods “to the maximum extent practicable,” laying the groundwork for sourcing U.S.-made and U.S.-grown products whenever feasible. Eight years later, the Berry Amendment of 1941, passed during World War II, specifically required the Department of Defense to procure food, clothing and other materials produced in the United States, a rule that continues to guide military food purchases today.

Post-war legislation linked domestic farm support directly with public feeding programs. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1935 created Section 32, dedicating a portion of customs revenues to purchasing surplus U.S. commodities for distribution in nutrition programs. When Congress passed the National School Lunch Act of 1946, it formalized this connection; school meals would not only improve child nutrition but also create a steady outlet for domestically produced food.

Congress later reinforced these requirements. The William F. Goodling Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act of 1998 added an explicit Buy American clause requiring schools to purchase domestic foods “to the maximum extent practicable.” Subsequent executive orders, most recently in 2021, have strengthened these rules across agencies, underscoring bipartisan recognition that U.S.-grown food purchases bolster both food security and the farm economy.

Federal Spending on U.S.-Grown

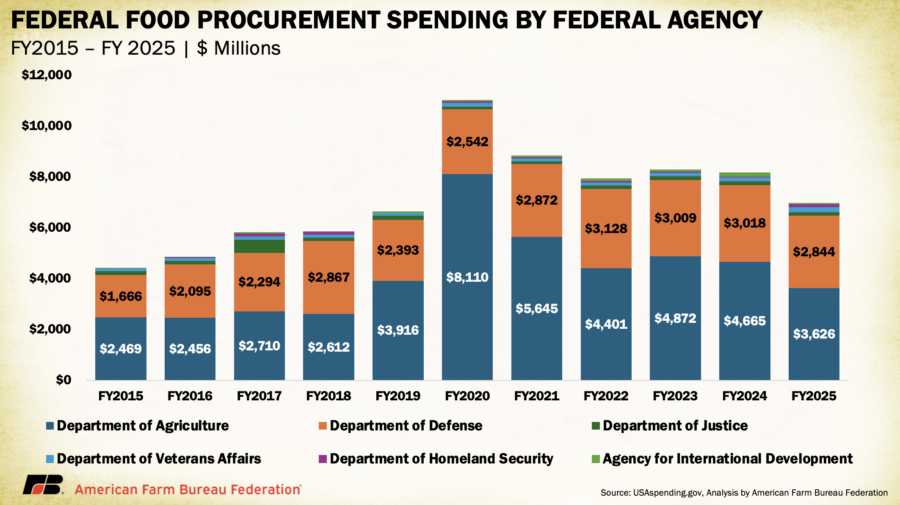

In fiscal year 2025, the federal government purchased $6.9 billion in U.S.-grown food and agricultural products across multiple agencies, according to USAspending.gov. While that represents less than 1% of total annual at-home food spending by American households, it plays an outsized role in supporting farm demand and market stability.

USDA accounted for $3.6 billion, or about 52%, of total federal food purchases. The Department of Defense followed with $2.8 billion (41%), supplying military installations and service members across the globe. The remaining 7% came from other agencies, including the departments of Veterans Affairs, Justice, and Homeland Security, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which use American-grown food in hospitals, correctional facilities, emergency response programs and international food aid.

Annual totals fluctuate based on economic and policy conditions. In fiscal year 2020, for instance, federal food purchases peaked at $11 billion as Congress and USDA deployed emergency programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. From fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024, overall procurement remained above earlier levels, reflecting supplemental “bonus buys” to stabilize farm prices and replenish food assistance pipelines.

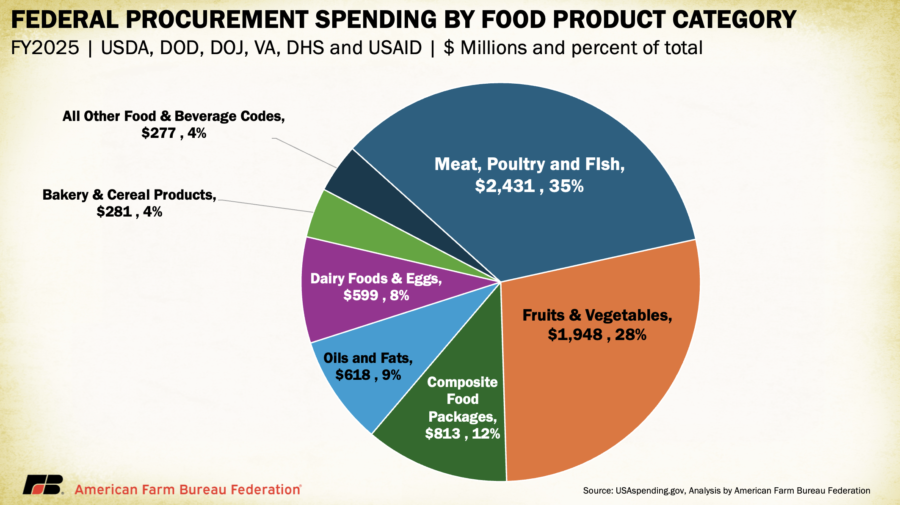

By commodity group, meat, poultry and fish products made up the largest share of fiscal year 2025 spending at $2.4 billion (35%), followed by fruits and vegetables at $1.9 billion (28%). Composite food packages, multi-ingredient items such as ready-to-eat meals, combination entrées or bundled canned goods used in food aid and institutional feeding, accounted for $813 million (12%). The remainder was divided among oils and fats (9%), dairy and eggs (8%), bakery and cereal products (4%) and other categories (4%).

USDA Nutrition Programs: The Cornerstone of U.S.-Grown Preference

USDA’s child-nutrition programs remain the largest and most visible federal outlets for American-grown food. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) serve about 30 million children daily and provided more than 4.86 billion meals in 2024. By law, participating schools must source domestic foods whenever possible.

A “domestic commodity or product” is defined as one produced in the United States, or processed in the U.S. using at least 51% U.S.-grown ingredients (by weight or volume). That definition leaves significant room for foreign content (nearly half the product could originate abroad), and there is no consistent mechanism to verify ingredient sourcing. Schools may only purchase foreign items if (1) the product is unavailable domestically in sufficient quantity or quality or (2) the U.S. product’s cost is significantly higher.

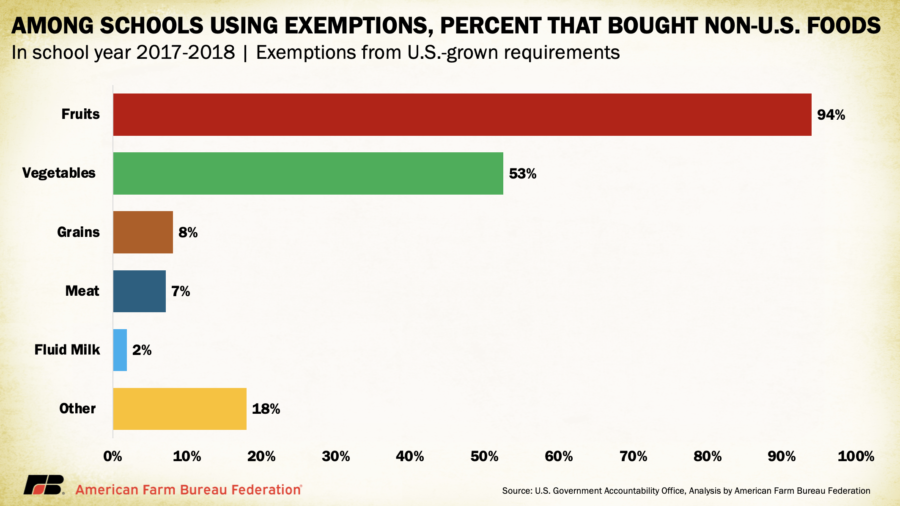

In practice, most exceptions apply to fruits that cannot be grown commercially in the continental U.S., such as bananas and pineapples. According to the Government Accountability Office, 94% of districts reporting exceptions used them for fruit, while 55% used them for vegetables. GAO found that 88% of exception users pointed to limited domestic supply as the primary reason; 43% said U.S. prices were too high; and roughly one in five noted differences in product quality. In one example, a district in the Midwest reported that even when domestic canned peaches were available, imported alternatives cost nearly 30% less per case.

Still, GAO emphasized that these figures represent only the subset of districts that reported using exceptions, many others do not consistently track or disclose the share of non-domestic purchases. USDA’s new rule, finalized in 2024, limits non-domestic foods to 10% of total costs beginning in school year 2025–2026, tightening to 5% by 2031. While that cap and new documentation requirements will improve transparency, they do not address the broader gap that under current rules, a product can still qualify as “domestic” even if 49% of its ingredients are sourced abroad. Items like fruit cups made with imported pineapple, juice blends using foreign concentrates, fish sticks processed from imported fillets and baked desserts made with palm oil could all incorporate more U.S.-grown ingredients where domestic substitutes exist.

Beyond the Lunchroom: USDA Foods and Institutional Procurement

Beyond school meals, USDA’s broader food purchasing programs extend domestic preference across a wide range of nutrition and food aid channels. Through the USDA Foods program, the department buys and distributes 100% American-grown commodities for use in the NSLP, Child and Adult Care Food Program, Summer Food Service Program and The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP). These purchases include U.S.-produced meats, dairy, grains and processed fruits and vegetables that meet federal origin and quality standards, accounting for about 10% of total school meal assistance.

Another key channel, the Department of Defense Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (DoD Fresh), uses USDA funds and military logistics networks to supply schools and childcare centers with fresh, American-grown produce. Operating in 49 states, the program distributed roughly $590 million in produce in fiscal year 2023, about 15% of which was sourced locally within participating states or regions.

USDA’s authority to make “bonus buys” through Section 32 and the Commodity Credit Corporation further reinforces markets when supply outpaces demand. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these authorities underpinned programs like Farmers to Families Food Boxes, which directed billions of dollars in domestic produce, meat and dairy to households in need. Between fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2023, fruits, vegetables and tree nuts accounted for roughly half of USDA’s food purchases by value, reflecting both stronger produce demand and the success of policies that tie nutrition goals to American farm support.

Room to Grow

Across decades of policy, the United States has built a strong foundation for sourcing American-grown food in public programs, from school meals and food banks to military bases and hospitals. These systems work largely as intended, ensuring that taxpayer dollars reinforce U.S. agriculture while feeding millions of Americans each day.

Still, enforcement and transparency lag in ways that limit their full potential. Strengthening Buy American oversight, tightening the definition of “domestic” and improving documentation of exceptions would help ensure federal nutrition dollars consistently support U.S. farmers. Even modest improvements could redirect millions of federal dollars back into American farms, bolstering both rural economies and national food security.