WOTUS and the American Farmer: Understanding the Regulatory Reach

TOPICS

WOTUSCourtney Briggs

Senior Director, Government Affairs

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Courtney Briggs

Senior Director, Government Affairs

Market Intel, produced by the Farm Bureau economic analysis team, provides market and policy insight and analysis for our farmer and rancher members nationwide, as well as policymakers on Capitol Hill. This Market Intel is a special policy analysis on the recently proposed waters of the United States rule.

Key Takeaways:

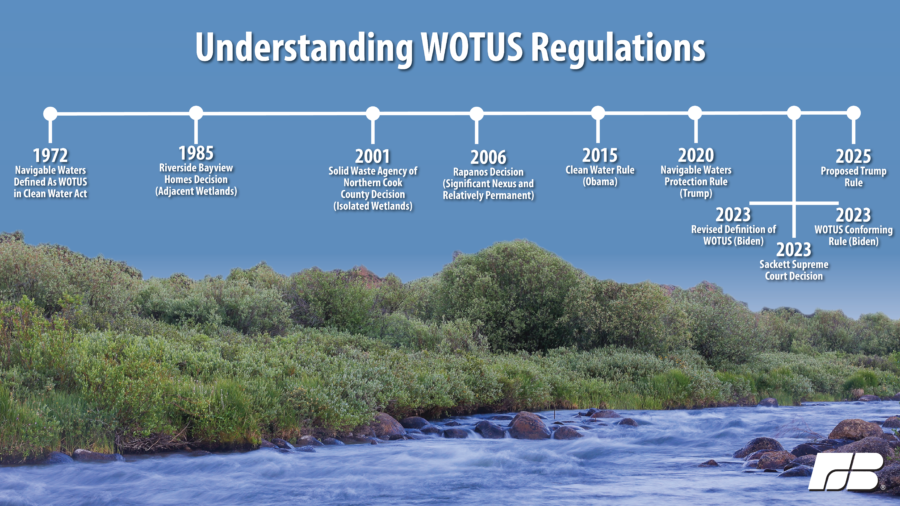

- For decades, the definition of “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act has been unclear, leading to regulatory uncertainty. Five rule changes since 2015 and conflicting court decisions created a “ping-pong” effect, leaving farmers unsure which water features on their land fall under federal jurisdiction.

- In their ruling in Sackett v. EPA, the Supreme Court eliminated the “significant nexus” test, which broadened the federal government’s jurisdictional reach. The ruling clarified that only relatively permanent waters and wetlands with a continuous surface connection to regulated waters fall under federal jurisdiction. This decision was widely praised for providing the clearest legal standard in decades.

- The Trump administration’s proposed WOTUS rule adopts Sackett’s framework, excluding isolated ponds, disconnected wetlands, and most ditches. It shifts the burden of proof from landowners to the federal government and allows states to regulate beyond federal standards. While the rule aims for clarity, challenges remain — such as proving sustained flow during wet seasons.

For years, farmers and ranchers have worked their land with a close eye on the weather, volatile markets, farm policy and the many regulations that shape everyday business decisions. Among the most influential, and often most confusing of these rules, is the definition of “waters of the United States” (WOTUS). Over the past decade, frequent regulatory changes and court decisions have left many farmers questioning what WOTUS really means for their operations. From the start of this debate, the American Farm Bureau Federation has been the leading voice across industry sectors, consistently advocating for clear, practical regulations that protect farmers while ensuring environmental stewardship.

The Evolving Definition of WOTUS

Under the Clean Water Act (CWA), the term WOTUS serves as the threshold that determines which water bodies fall under federal jurisdiction. Unfortunately, the statute offers little clarity on where that jurisdictional line should be drawn. Over the years, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the agencies) have exploited this ambiguity, expanding their authority far beyond what Congress intended when drafting the law.

From the mid-1980s onward, the agencies operated under a regulatory definition that broadly interpreted WOTUS to include many waters. This expansive interpretation repeatedly ran up against judicial scrutiny. The Supreme Court’s decisions on the limits of the federal government’s regulatory reach, in cases such as Riverside Bayview Homes, Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County, and Rapanos,

often created more questions than answers.

For example, the Supreme Court’s 4-1-4 split in Rapanos created conflicting standards for federal jurisdiction. Justice Scalia’s plurality introduced the “relatively permanent waters” test, while Justice Kennedy’s concurrence advanced the “significant nexus” test. With no majority opinion, this fractured guidance left regulators and courts without a clear rule, fueling years of litigation and inconsistent interpretations as successive administrations struggled to define WOTUS.

Beginning in 2015, the regulatory uncertainty was exacerbated as different presidential administrations attempted to make sweeping changes, creating a swinging pendulum of regulations. Consequently, the definition of WOTUS became a legal and regulatory maze — one in which wetlands, ditches, seasonal streams, drainage features or even ephemeral streams (low spots in a farm field) could be regulated. Over the last decade, there have been five different rulemakings on WOTUS. The ping-ponging of definitions has produced anxiety and uncertainty for farmers and ranchers whose decisions on the farm depend heavily on clear rules.

Sackett v. EPA: A Turning Point for WOTUS Clarity and Certainty

The 2023 Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA marked one of the most consequential shifts in federal water regulations since the passage of the CWA. This decision greatly narrowed the types of water features and wetlands regulated as a WOTUS and simplified compliance for landowners. The Supreme Court accomplished this by unanimously eliminating the troubling “significant nexus” test, which allowed the federal government to set up a case-by-case regulatory regime that expanded their jurisdictional reach beyond legal boundaries.

Additionally, the ruling greatly restricted the types of wetlands that fall under federal authority by providing proper guardrails for “adjacent wetland.” Farmers and ranchers across the country praised the Court’s decision because it is the clearest, most decisive legal standard for WOTUS in decades and appropriately reigns in the federal government’s authority.

Understanding the Proposed WOTUS Rule

On Nov. 17, 2025, the Trump administration proposed a new WOTUS definition that implements the Sackett decision and upholds congressional intent under the CWA. The rule represents the greatest narrowing of the federal government’s jurisdictional reach over private property. As directed by the Supreme Court, the proposal only regulates water bodies that are “relatively permanent” — meaning surface waters that flow or stand year-round or those that flow throughout the wet season — and wetlands that are directly abutting a regulated tributary and have a continuous surface connection.

As an example, features like isolated ponds, field-edge depressions, disconnected wetlands, groundwater and many ditches or prior-converted cropland would be excluded. The rule also proposes to define key terms (like “tributary,” “ditch,” “prior converted cropland,” etc.) to bring consistency and predictability to what is “in” and what is “out.” This also reduces the amount of land subject to the regulation, cutting down regulatory costs across the industry.

Most importantly, this rule shifts the burden of proof away from the landowner and places this responsibility squarely on the federal government, meaning a farmer no longer must prove that they do not have a WOTUS on their property to use their land.

It is critical to recognize that this rule upholds the cooperative federalism objective of the CWA by allowing states to serve as the primary authority in regulating water. State governments can regulate far beyond the definition of WOTUS and impose their own, more stringent rules. In many states, just because a water feature is not regulated by the federal government, does not necessarily mean that it goes unregulated.

While this rule is an important step forward in creating a legally durable definition of WOTUS, implementation of the rule may present some challenges. One potential hurdle for some landowners will be determining if there is sustained flow throughout the wet season. In some instances, field-level data may need to be collected, which could significantly slow down the jurisdictional determination process. This also impedes farmers’ ability to use their land, potentially cutting their production and revenue capacity.

The Cost of Compliance

Ensuring compliance under WOTUS for farmers can include several major components that impact a farmer’s cost of production:

- Obtaining Clean Water Act federal permits for activities like fencing, drainage or pond construction;

- Hiring consultants and technical experts for wetland determinations;

- Experiencing operational delays while waiting for permit approvals; and

- The cost of mitigation activities which can often be substantial.

Because Clean Water Act compliance carries significant civil and criminal liabilities — up to $64,000 per day or even jail time — it is critical that farmers fully understand the rules to avoid inadvertent violations.

How WOTUS Shapes Everyday Farm Decisions

Farmers care about the definition of WOTUS because it determines which ditches, wetlands and water features on their land fall under federal regulation — and therefore which everyday activities may require permits, carry compliance obligations or expose them to legal risk and regulatory costs to ensure compliance. Whether they are installing tile, building a fence, cleaning out a ditch, expanding cropland or managing drainage after heavy rains, the scope of WOTUS directly influences what farmers can do without federal oversight.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL