Back to Whole? How School Milk Could Shift Dairy Demand

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Farmers and ranchers are facing rising costs, weak prices and uneven global competition that threaten their ability to stay in business. At the same time, policy decisions in Washington can increase market access, spur demand growth and ensure fair competition. This new Market Intel series will examine six priority policy areas - trade, biofuels, whole milk in schools, interstate commerce, transparent input markets and prioritizing U.S.-grown produce - and how each can help strengthen the farm economy and rural communities.

More than a decade after whole milk was removed from school cafeterias, Congress is reconsidering whether students should have the freedom to enjoy it – and its many nutrients. The Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act (H.R. 649/S. 222) would overturn USDA’s 2012 restrictions that have limited schools to providing only fat-free or 1% milk. The proposal, which aligns with recommendations from the Make America Healthy Again Commission, comes as policymakers, farmers and processors look to revitalize a category that has steadily lost market share and reconnect children to the benefits and taste of milk.

Behind the policy debate lies a broader market story: U.S. milk production is on pace to reach a record high in 2025 even as fluid consumption continues to decline. Allowing whole milk back into schools could provide a small but meaningful outlet for butterfat, a key driver of farm milk value, while giving local dairies new opportunities to serve their communities.

Background: Shifting Dairy Consumption

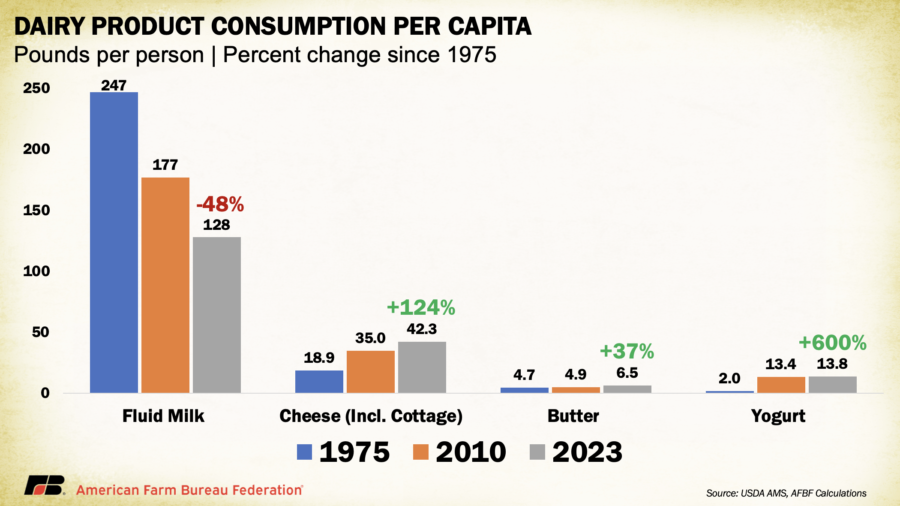

Fluid milk consumption in the U.S. has fallen nearly 50% since 1975 (from 247 pounds per person to 128 pounds in 2023), including a 28% drop since 2010. The decline is not uniform across dairy products, however. Cheese consumption (including cottage cheese) more than doubled from 18.8 pounds per person in 1975 to 42.3 pounds in 2023 (+124%). Butter use climbed from 4.7 to 6.5 pounds (+37%), and yogurt intake surged over 600%, from 1.9 to 13.8 pounds over the same period.

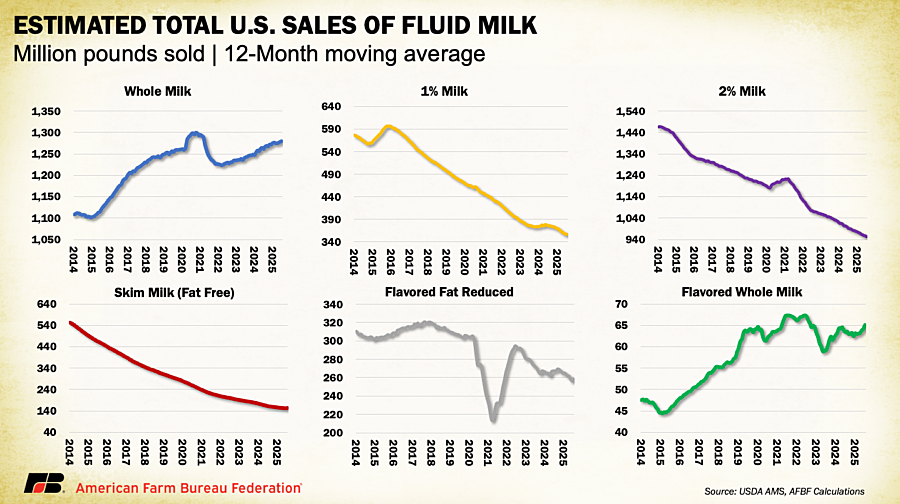

Whole milk stands out as a rare success story within the beverage category. Between 2013 and 2024, sales of whole and flavored whole milk grew by 16% (+2 billion pounds), while reduced-fat options lost ground: skim (–72%), 1% (–36%), 2% (–33%). Whole milk’s share of total beverage sales rose from 27% to 38%.

Some consumers have shifted from reduced-fat to whole milk options, driven by the “protein boom,” renewed interest in minimally processed foods and perhaps, more recently, growing demand among users of GLP-1 medications (drugs such as Ozempic and Wegovy that suppress appetite) for fuller-fat, higher-protein options that promote satiety and sustained energy. Recent research indicates that about 38% of GLP-1 users report drinking more protein beverages, though it remains unclear whether this trend has specifically boosted whole milk consumption.

At the same time, complementary products like breakfast cereal have declined in popularity, eroding one of milk’s strongest consumption anchors. Cereal and milk are natural complements; as more consumers opt for coffee, breakfast bars or yogurt cups on the go, both cereal and milk sales have suffered.

Policy History: How Whole Milk Disappeared

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP), established in 1946, provides nutritious, low-cost meals to nearly 30 million students each day. Because schools account for roughly 7.5% of U.S. fluid milk sales, NSLP nutrition rules have long influenced dairy demand. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 sought to improve school nutrition by capping sodium, calories and saturated fat. Beginning in the 2012–13 school year, USDA rules restricted milk served in schools to fat-free or 1% varieties. Whole and 2% milk were no longer allowed, and flavored milk had to be fat-free. Later updates permitted 1% flavored milk, but whole and 2% options have remained prohibited.

The rule coincided with a drop in student milk consumption. Between 2008 and 2018, weekly milk use per student fell from 4.03 to 3.39 cartons (–15%). Before 2012, consumption declined by 0.03 cartons per year; after the restriction, the rate accelerated to 0.13 cartons — a 77% faster decline. When students skip milk, both nutrition goals and dairy demand suffer. Those unopened cartons also create measurable food waste, raising costs for schools already operating on thin budgets.

The Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act

The bipartisan Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act introduced by Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson (R-Pa.) in the House and Sen. Roger Marshall (R-Ks.) in the Senate, would restore flexibility by allowing schools to serve whole, 2%, 1%, or skim milk (flavored or unflavored) as reimbursable meals. It also clarifies that milkfat would not count toward the saturated-fat limit under school meal guidelines, ensuring compliance without penalizing higher-fat milk. The legislation includes a supply-chain requirement barring procurement from Chinese state-owned enterprises. As of October 2025, the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act has advanced out of both the House Education and Workforce Committee and the Senate Agriculture Committee by voice vote, but has yet to be considered by the full House or Senate for final passage.

Notably, the act does not mandate that schools switch to whole milk; instead, it permits them to do so. This distinction is central to how the market could react. Because adoption would likely occur gradually, driven by local preference, supplier capacity and budget realities, the resulting increase in milkfat demand would build over time rather than appear all at once.

Potential Market Impacts

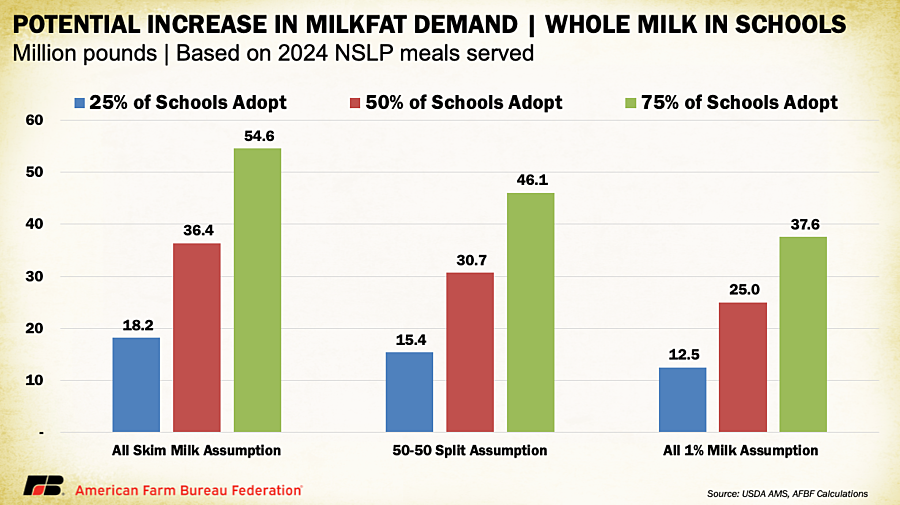

Restoring whole milk to school menus would not mandate a universal switch, but even moderate adoption could reshape component demand across the dairy sector. The National School Lunch Program served 4.86 billion meals in 2024, with roughly 85% of students selecting milk — about 4.13 billion half-pint cartons of skim or 1% milk. Each carton of whole milk contains about 8 grams of fat, compared to 2.5 grams in 1% milk and virtually none in skim. This difference means that if schools begin offering whole milk again, every serving would draw an additional 5.5 to 8 grams of butterfat into the fluid stream that currently gets separated for butter, cheese or milk powder.

Under an all-skim baseline, if 25% of schools adopt whole milk (representing an early, conservative estimate), total milkfat utilization would rise by roughly 18 million pounds annually. If half of all schools make the switch, the increase grows to about 36 million pounds, and if three-quarters of schools adopt whole milk, the added fat demand reaches 55 million pounds per year. Assuming current milk offerings are evenly split between skim and 1%, the same adoption levels would boost butterfat demand by 15 million, 31 million and 46 million pounds, respectively. Even under the more conservative all-1% baseline, increased milkfat demand would total 13 million, 25 million and 38 million pounds across the three adoption tiers, respectively.

At the high end, a near-universal shift to whole milk could divert the equivalent of 45 million to 66 million pounds of finished butter into fluid use each year, based on the Federal Milk Marketing Order yield assumption that 1 pound of butterfat produces about 1.21 pounds of butter. That amounts to roughly 2-3% of total U.S. butter production, a significant reallocation of components from manufactured to beverage markets. This shift would come at a time when U.S. dairy farmers have already answered the call for more butterfat (boosting average butterfat levels more than 13% over the past decade) and would help capture greater value from that production in a market that often struggles to absorb the surplus fat. In practical terms, this means the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act could modestly tighten butter and cream supplies while lifting Class I utilization and overall blend prices.

Between January and July of this year, Class I (fluid) milk accounted for about 25% of total U.S. milk use (23 billion of 92 billion pounds). Increasing school milk sales and milkfat utilization would strengthen this category, which carries the highest regulated value under the recently amended Federal Milk Marketing Orders. Those changes, which restored the higher-of Class I mover and raised Class I differentials, already improved returns on milk sold into fluid channels. By pulling more butterfat into Class I use, schools could amplify the benefit of those reforms, helping to raise the uniform price farmers receive.

Even marginal increases in fluid demand can matter in an industry often oversupplied by just a few percentage points. Redirecting cream to bottled milk reduces low-value skim powder output, while higher butterfat utilization supports the value of components across all classes. For processors, whole milk simplifies production and reduces drying and storage costs. For smaller dairies, particularly those without separators, the ability to bottle and sell whole milk locally could open new farm-to-school opportunities.

Conclusion

While the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act would represent only a modest change in total milk use, it targets one of the few demand streams that can grow in the currently saturated market. Even small shifts in school milk sales can strengthen the Class I category, lift butterfat utilization and return more value to farmers. With 2025 milk production tracking at record highs and U.S. butterfat output already at historic levels, expanding whole milk options in schools would help absorb supply where it matters most — connecting students to the benefits and taste of milk and farmers to stronger milk checks.