USDA Releases Long-Awaited Industrial Hemp Regulations

TOPICS

USDAMichael Nepveux

Former AFBF Economist

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Philip Gerlach

Michael Nepveux

Former AFBF Economist

Introduction

On Tuesday, Oct. 29, USDA released the text of its interim final rule for regulations establishing a domestic hemp production program. Since this is an interim final rule, it will be in effect immediately upon being published in the Federal Register. The 2018 farm bill legalized the production of hemp as an agricultural commodity while removing it from the list of controlled substances (2018 Farm Bill Provides A Path Forward for Industrial Hemp). Industrial hemp is defined as Cannabis sativa L. and required to be below a THC threshold of 0.3%. Hemp production is legal in 46 states and the farm bill allows Idaho, Mississippi, New Hampshire and South Dakota to continue to ban production of the crop within their borders.

Ever since the 2018 farm bill was signed, farmers, regulators, stakeholders and law enforcement have been operating in a state of uncertainty as they waited for USDA to release this guidance. As is always the case in such circumstances, the rule doesn’t make everyone totally happy and there are still a few lingering questions. However, the department deserves significant credit for putting together a comprehensive set of regulations for a complicated issue in a relatively short period of time.

General Overview on Regulations for Hemp Production

In order to produce hemp, a farmer must first be licensed or authorized under a state or tribal hemp program or through the USDA hemp program. If a state or Indian tribe desires to have primary regulatory authority over hemp production in their borders, they may submit a plan for monitoring and regulating hemp production to USDA. States that have already submitted a plan will be given the chance to reaffirm the plan they want USDA to evaluate, or to submit a new plan if desired. The rule also establishes a USDA plan to regulate hemp production in states or areas where hemp production has been legalized, but no approved state plan is in place. Farmers may not grow hemp in states that have not legalized its production within their borders. Once a license application has been approved, USDA will issue a license. License applications will not be approved until Nov. 30, and a farmer cannot receive a hemp production license from a state, tribe or USDA if he/she has been convicted of a felony related to a controlled substance in the last 10 years.

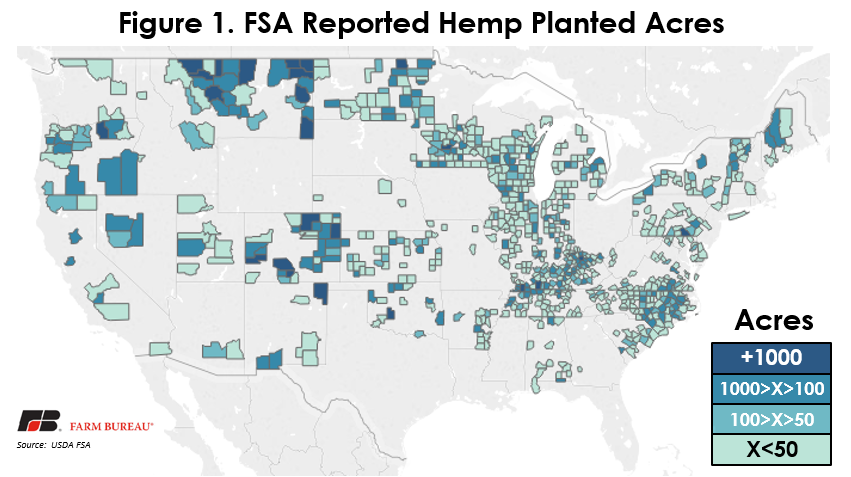

In addition to the land information that must be submitted to the appropriate state or tribe, licensed farmers are also required to report their hemp crop acreage to the Farm Service Agency. This will give USDA and stakeholders a better idea of how much hemp is planted and grown in the U.S., as it is currently difficult to obtain this information. FSA reports crop acreage, including hemp, but the hemp acreage is underreported because it was not mandatory for farmers to provide the information. However, the numbers that were reported provide a general idea of where in the country hemp is grown, and at least provide a lower limit baseline to start with (Figure 1).

Remaining Under the THC Limit and Testing Procedures

A key cause of heartburn for farmers was the potential of a hemp crop coming in at a THC concentration above the 0.3% threshold. Unfortunately, seeds grown in two different geographical regions can express certain traits differently, i.e., the same type of seed grown in two different parts of the country can produce one crop with THC concentrations less than 0.3% and another with plants above that THC threshold.

Stakeholders were hoping these regulations would provide some clarity on the testing process as there was little uniformity across states in how the crop would be tested; some states would just test the top 8 inches of a plant, while others would test 6 inches, and there was little consistency in how to build up a statistically significant sample of a farmer’s crop.

These regulations require the crop be tested within 15 days prior to the anticipated harvest. There is still some confusion surrounding this. For example, if a sample is pulled 15 days before anticipated harvest, would harvest be allowed if there is a backlog at the testing laboratory and the results are not back in time? The THC concentration typically increases as the plants mature, so a crop could potentially rise above the threshold if the testing process isn’t completed early enough in those 15 days. Additionally, does the 15-day window mark the beginning of harvest or the end of harvest? Some fields may take multiple days to harvest and could conceivably be started before but finished after the 15-day window closes. USDA is requesting public comment and information regarding this sampling and harvest timeline.

Testing procedures must ensure the testing is completed by a Drug Enforcement Administration-registered laboratory using a reliable methodology for testing the THC level. USDA has issued sampling and testing procedure guidelines in separate documents attached to this interim rule. Part of the reasoning for this is to allow the department flexibility as new technologies and procedures are developed over time. Setting the testing and sampling procedures outside of the interim rule allows the guidance documents to be improved without going through an all-out rulemaking.

These new rules acknowledge the statistical uncertainty that comes with sampling and testing a hemp crop for THC. The regulations allow for the inclusion of the measurement of uncertainty as laboratories report THC test results. Essentially, the measurement of uncertainty could be understood to be similar to a margin of error (or for the economists in the room: confidence interval). When the measurement of uncertainty (e.g. +/- 0.05) is combined with the reported measurement, it produces a range resulting in the actual measurement having a known probability of falling within that range. If the 0.3% THC limit is within the range, then the sample will be considered to be hemp under these regulations, and not rise to a controlled substance. For example, say a laboratory reports a result of 0.33% THC with a measurement uncertainty of +/- 0.04. The distribution ranges from 0.29% to 0.37%, and because 0.3% is within that range, the sample will be considered industrial hemp. Again, for the economists and statistics nerds tuning in, think of a hypothesis test that fails to reject the null hypothesis that the result is statistically different than 0.3%. The measurement of uncertainty depends on multiple variables, such as the equipment being used, the methodology of the test, the sample size, the sample quality and other variables, and as such it will vary with each sample that is tested.

These new rules also acknowledge the fact that a farmer may unintentionally produce a crop that tests over the limit despite their efforts to produce a crop that complies with federal law. The rule determines that a producer does not commit a negligent violation if they produce plants that exceed the acceptable hemp THC level as long as they use reasonable efforts to grow the plant and it does not test at more than 0.5% THC on a dry weight basis. Although a farmer testing above 0.3% but below 0.5% may not be negligent, the crop is still considered a controlled substance and must be disposed of accordingly. While states and tribes will differ in how they handle farmers who become negligent, at a minimum, if a farmer negligently violates a state or tribal plan three times in a five-year period, they will be ineligible to produce hemp for the next five years. Additionally, negligent violations are not subject to criminal enforcement action.

Disposal of ‘Hot Crops’

Before the release of the interim rule, some in the industry were hoping for flexibility in the disposal of “hot crops,” or hemp crops that test over the 0.3% THC limit. Many were hoping for rules that would let farmers dispose of the plants in a more productive manner, such as composting or for soil amendments. Farmers will put considerable time, cost and effort into the crop, and it would be a shame to have to completely destroy the product with nothing to show for it. Ultimately, this rule does not address this problem the way farmers hoped. However, this aspect of the rule was essentially out of USDA’s hands. If a crop is above the THC limit, it is considered to be marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act and must be disposed of accordingly. Laws and regulations for the procedures of destroying a controlled substance are not set by USDA, and so the department was constrained in how it could address this issue. It will have to be collected for destruction by someone authorized to handle a Schedule I controlled substance, such as a DEA-registered reverse distributor or a federal, state or local law enforcement officer. Farmers must document the disposal of the crop, which is now considered marijuana. This can be accomplished by providing USDA with a copy of the documentation of disposal provided by the authorized agent or by using reporting requirements established by USDA.

Interstate Commerce

The issue of interstate commerce arises when something, like industrial hemp, is legal in some states and at the federal level, but illegal in other states. There are still four states in which growing hemp is not legal, and since the 2018 farm bill was passed, the issue of transportation has been somewhat of a grey area. As an example, earlier this year, Idaho state police seized a truck carrying $1.3 million worth of hemp cultivated lawfully in Oregon that was on its way to Colorado for processing. In the 2018 farm bill and in a legal memo USDA affirmed a state’s right to enact and enforce laws regulating the production of hemp within its borders, but explicitly stated that a state or Indian tribe may not restrict the transportation of hemp within its borders. These new regulations reaffirm that no restrictions on the transportation of hemp may occur, providing farmers access to nationwide markets.

Clarity for Financial Institutions

Prior to the rule, many in the banking sector were looking for additional clarity on the legal and regulatory landscape surrounding financing in the hemp sector. Even though hemp production was legalized under the 2018 farm bill, many banks concluded the regulatory uncertainty (especially when factoring in marijuana, which is legal in many states, but illegal at the federal level) presented too great of a legal risk and opted to not participate in financing hemp production. There has been some movement over the past year to provide additional certainty, including the passage of the SAFE Banking Act in the House. However, financial institutions still remain wary of participating in this market. The banking industry has been awaiting these regulations in order to develop their own procedures regarding deposits from hemp operations. Hopefully with the release of this rule, the banking industry will develop appropriate guidance, allowing farmers to obtain financing and utilize other financial services if they produce hemp.

Felony Background Check on Workers

The 2018 farm bill limited the participation of certain convicted felons in hemp production. A person with a state or federal felony conviction relating to a controlled substance is subject to a 10-year ineligibility restriction on producing hemp, with an exclusion for those who were lawfully growing hemp under the 2014 farm bill. A question that had been subsequently raised was whether or not this restriction would only apply to the owner of the operation applying for the license, or if this would apply to every employee on the operation. Basically, in an industry already suffering from increasing labor shortages, is it really necessary to limit the pool of labor by requiring every field hand, tractor driver or janitor be subjected to this background check before an operation can grow hemp? This is an issue where the rule provides much-needed relief and clarity for producers. When filing an application to grow hemp, farmers must provide a completed criminal history report, and if the application is for a business entity, the criminal history report must be provided for each “key participant.” The rule goes on to clarify that a key participant is any individual who has a direct or indirect financial interest in the business entity, such as an owner or partner. The definition does not include shift managers or field workers. Thankfully, these rules do not make it more difficult to secure reliable farm labor.

Crop Insurance and Other Programs

After the farm bill authorized industrial hemp as a covered crop under crop insurance, some of the insurance-related uncertainty was moderated when USDA issued a bulletin in early 2019 establishing that a farmer who derived part of his or her revenue from hemp would not be found ineligible to participate in the Whole Farm Revenue Protection Plan. The bulletin also stated that hemp as a commodity was not insurable for the 2019 crop year. Later in 2019, Congress included a provision in the Disaster Relief Act requiring the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation to offer coverage under WFRP for hemp in the 2020 reinsurance year.

This interim final rule does not necessarily provide more information or clarity about crop insurance but having the rule in place is critical for hemp farmers looking to manage their risk through crop insurance. For FCIC to offer the WFRP policy in 2020, this interim final rule must take effect this fall to provide USDA’s Risk Management Agency sufficient time to take the necessary steps for authorization and for producers to start their own steps to qualify for coverage. For the 2020 crop year WFRP is available for hemp grown for fiber, flower or seeds. In order to participate in crop insurance, a farmer will need to certify acreage with FSA and identify each field, subfield or lot in which hemp is grown. Additionally, a farmer will be required to have a contract for the purchase of the hemp before being able to purchase insurance. One key point that has been made by RMA is that a crop breaching the 0.3% THC limit is not considered a covered loss under WFRP, even if that may be driven by weather conditions.

Summary

These new regulations offer much-needed guidance for farmers and others involved in the production of industrial hemp. Importantly, we now have a better idea of how the crop will be sampled and tested for its THC content and what happens when a crop breaches the 0.3% THC limit. USDA has acknowledged some of the uncertainty surrounding testing and understands that a farmer could do everything right but still have a “hot crop” and should not be unduly punished for results outside of their control. Also, the rules, thankfully, do not make it more difficult to secure reliable farm labor and they reaffirm that states that have not legalized hemp may not interfere in the interstate transportation of the crop.

Having these rules in place make it possible for other agencies and industries, such as financial institutions and crop insurance providers, to begin establishing their own guidelines and procedures for dealing with industrial hemp. While it is impressive that the department was able to put together a comprehensive set of regulations for a complicated issue in a short period of time, questions remain about some aspects of hemp production. USDA is requesting public comment on these questions and it is important for farmers and stakeholders to participate in the process.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL