Wolves and the West: The Cost of Coexistence

TOPICS

Wildlife

photo credit: Getty Images

Daniel Munch

Economist

While the expansion of gray and Mexican gray wolf populations is often hailed as a conservation success, the consequences for ranching families can be gruesome, costly and complex - threatening the safety of ranch families and their pets and livestock, as well as the long-term survival of multigenerational ranches and the rural economies they anchor.

Focusing on the Mexican gray wolf, a recent University of Arizona study analyzes both direct livestock depredation and indirect effects such as stress-induced weight loss and elevated management costs based on 2024 cattle prices. Findings are based on survey responses from impacted ranchers, modeling of herd-level financial outcome and county-level livestock performance trends. In areas with wolf presence, even a moderate level of impact, such as 2% calf loss, 3.5% weight reduction and average management costs, can reduce annual ranch revenue by 28%.

While the study focuses on Mexican gray wolves in the Southwest, the core challenges it identifies, such as livestock depredation, herd stress and weight loss, increased management costs and difficulties accessing timely compensation, are not unique to that region. Ranchers across the Northern Rockies, Pacific Northwest and Great Lakes states report similar experiences as wolf populations have expanded. Because these economic stressors stem from common predator-prey dynamics and livestock production systems, the study’s findings provide a credible framework for estimating broader impacts. This Market Intel draws on that foundation to illustrate the tangible financial risks associated with predator recovery and highlight the need for responsive, producer-informed wildlife policy in all regions affected by wolf activity.

Background

When the gray wolf was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1978, the species was nearly extinct in all lower 48 U.S. states except Minnesota (where they were classified as threatened). The species’ steep decline was largely driven by federally supported predator control efforts and bounty programs aimed at eliminating wolves to reduce conflicts with livestock, pets and rural communities. Many ranching communities were established at the same time as government-backed removal, when wolf presence was minimal or nonexistent, shaping generations of land use and livestock management in their absence.

In 1982, Congress amended the Endangered Species Act to authorize the establishment of experimental populations of endangered or threatened species to aid in species recovery. After years of controversy, 66 gray wolves were ultimately released into central Idaho and Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and 1996. A few years later, in 1998, the Mexican gray wolf, the smallest subspecies of gray wolf, was reintroduced into the wild through a program centered in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, spanning rugged public lands across eastern Arizona and western New Mexico.

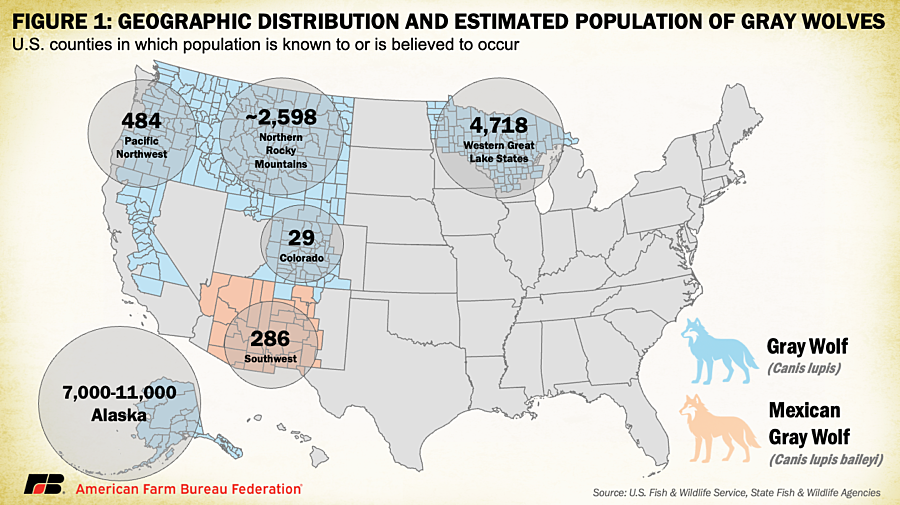

Most recently, after a state-wide ballot initiative supported the reintroduction of wolves in Colorado, Colorado Parks and Wildlife partnered with Oregon wildlife officials to translocate 10 gray wolves from multiple Oregon packs and released them onto state-owned public lands in Grand and Summit counties. Today, gray wolf populations have grown beyond their original reintroduction levels and regions, reflecting the success of recovery efforts and intensifying their presence on Western rangelands (Figure 1).

Direct Depredation

The most immediate and visible impact of wolf presence on rangelands is direct livestock loss from confirmed depredation. These incidents most commonly involve calves, but cows and more rarely, bulls, horses and dogs can also be affected. For ranchers, the loss of a calf represents a full loss in revenue, regardless of the animal’s age or weight at the time of death. Whether the calf was 1 day old or nearly ready for market, the rancher loses its full market value, estimated at $1,336 per head in 2024 (for a 525 lb. calf). Actual impacts may vary year to year depending on market prices.

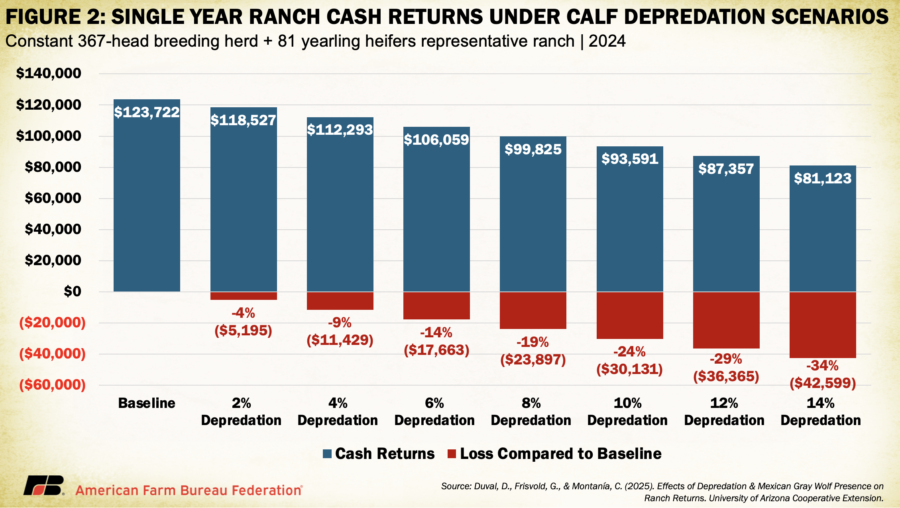

The University of Arizona study modeled the one-year impact of calf losses due to depredation. A 2% loss of calves could reduce a 367-head ranch’s net income by 4%, or about $5,195, for that year. At higher loss levels, such as 14% of calves, net income could fall by as much as 34%, or roughly $42,599, in that same year.

When a cow is killed, the financial hit extends over multiple years: the operation not only loses that year’s calf, but also future offspring, along with the revenue and herd stability that cow would have provided. Ranchers then have to more frequently retain replacement heifers or buy additional replacements. This means fewer animals are available for sale, working capital must be used to buy additional replacements and herd development is ultimately delayed. Excluding these long-term impacts, the revenue loss associated with the loss of a single cow was estimated at $2,673.

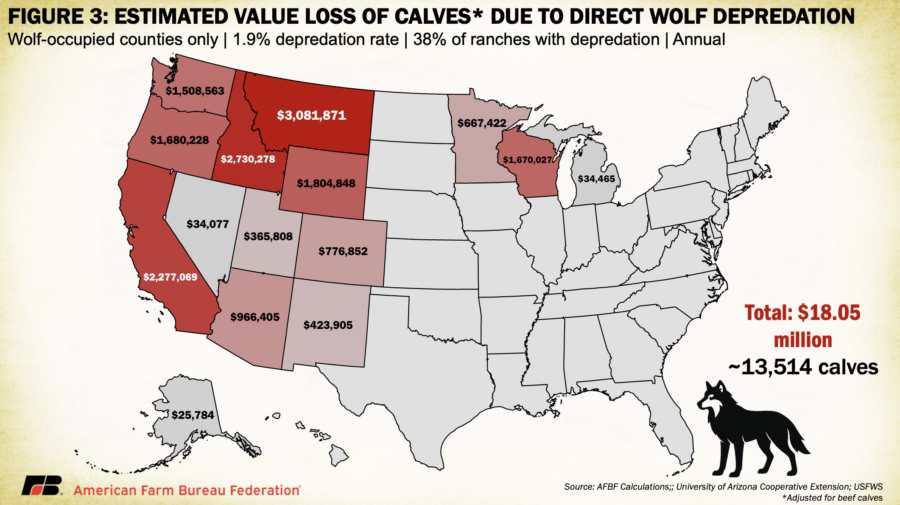

Depredation rates vary significantly between ranches, influenced by factors such as landscape features, alternative prey availability (e.g., deer and elk), proximity to roads or human development and whether wolves have recently visited the area. Previous analysis has estimated an average wolf-related calf depredation rate of 1.9%, though actual rates can vary widely. Importantly, only a subset of ranches within counties known or believed to have wolf presence experience predation. In the University of Arizona survey, 38% of respondents reported confirmed wolf depredation on their ranches.

For this broader analysis estimating total state-by-state losses attributed to wolves, we apply these assumptions to the number of beef calves estimated to be present in counties with wolf presence (as defined by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Calf numbers were derived using 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture data, with calves estimated to make up approximately 15% of total cattle inventory in states with wolf populations. To avoid overstating exposure, each county’s cattle inventory was adjusted to exclude dairy cows, which are generally less likely to graze on open rangeland.

Figure 3 displays the calculated value of calves lost under this scenario assuming each calf is valued at $1,336. This generates a loss of 13,514 calves out of an inventory of 1.87 million calves valued at $18 million in wolf-occupied counties. The states with the highest number of calf depredations under this scenario are Montana ($3 million; ~2,307 calves) and Idaho ($2.7 million; ~2,044 calves).

Keep in mind this method assumes static wolf presence at the county level. Wolves regularly traverse dozens of miles per day, crossing county and state borders, so county-level presence can vary widely year-to-year.

Indirect Losses: Physiological Stress

In addition to the loss of individual animals, the presence of wolves introduces chronic stress that can disrupt cattle health and productivity. Even without a direct attack, cattle sense predator cues, like scent, tracks or howling, which triggers a survival response. As a result, cattle spend less time grazing and more time bunched together, alert and on the move. This reduces forage intake, slows weight gain and lowers overall body condition.

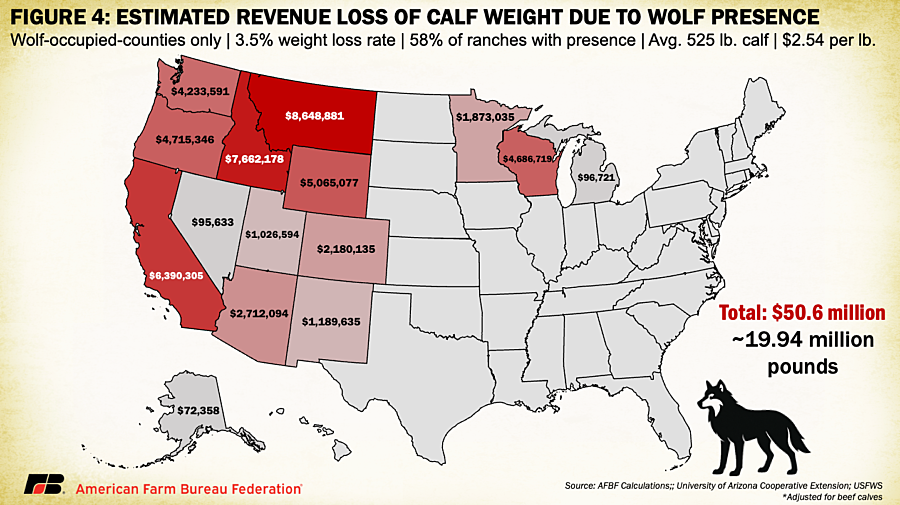

Stress can also suppress estrus cycles and reduce conception rates, especially in herds that have previously experienced depredation. Calves may wean at lower weights, lowering sale value. Importantly, these impacts often occur even on ranches that haven’t experienced direct losses, highlighting how just the presence of wolves can erode ranch profitability over time. The University of Arizona found 58% of those surveyed had stress- or depredation-related wolf impacts on their operation (compared to just 38% reporting depredation).

The Arizona model found that a 3.5% reduction in average calf weaning weight (18.4 pounds) — a figure supported by published field research — can significantly reduce revenues across an entire herd. At the $2.54 per pound value reference in their study ($1,336/ 525 lb. average), a ranch operation that markets 80 head would lose out on $3,738 in marketable weight value. Weight loss can be much higher in regions with elevated wolf activity. If that same ranch experienced a 10% reduction in weaning weight, the loss would exceed $10,600 before even factoring in additional impacts like reduced conception rates. Using these assumptions about ranch exposure to wolf presence and average weight loss, Figure 4 presents the estimated revenue loss by state. In total, over $50 million in potential calf weight value was lost due to wolf presence, including $8.6 million in Montana and $7.6 million in Idaho alone.

Increased Mitigation Costs

Beyond lost livestock and reduced productivity, wolf presence forces ranchers to change the way they manage their operations — often at a steep cost. In wolf-occupied areas, ranchers routinely implement additional strategies to deter predation, respond to attacks and monitor herds across expansive rangelands. These management efforts are both labor- and resource-intensive.

Preventative measures may include altering grazing rotations to avoid wolf-active areas, confining livestock during vulnerable periods, hauling feed and water to secure locations, and hiring range riders to maintain human presence near herds. Many producers also invest in tools such as trail cameras, turbo fladry (lines of fluttering flagging attached to electrified fencing used to deter wolves) and sometime access telemetry devices (like GPS collars) to track wolves and avoid conflict. These measures incur direct expenses in fuel, equipment, labor and supplemental feed, as well as indirect costs like deferred maintenance and lost time.

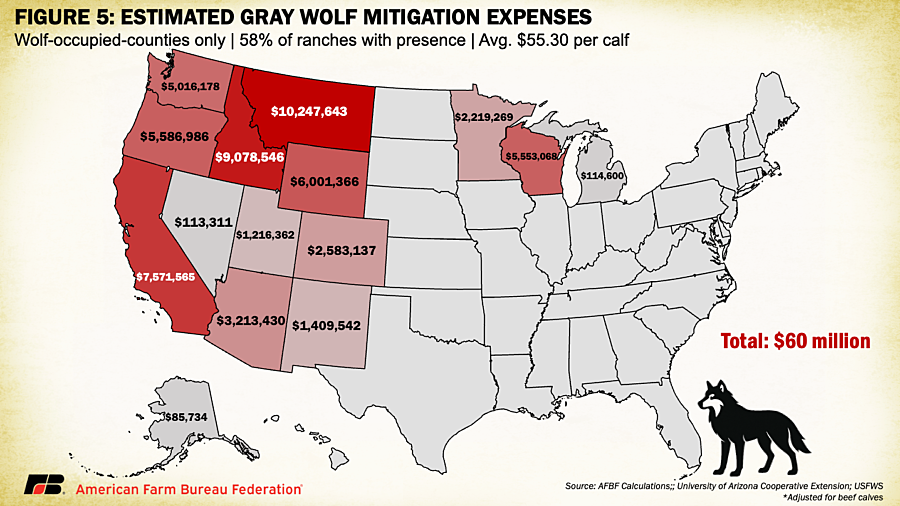

According to the University of Arizona study, ranchers reported an average cost of $79 per cow for conflict avoidance measures and associated labor. Even before accounting for any depredation or stress-related weight loss, these management expenses alone reduced net returns for the average ranch by 19%. Through interviews and surveys, producers indicated they spent anywhere from several thousand dollars to over $150,000 per year on these efforts. For our analysis, we convert the $79 per cow figure to $55.30 per calf based on their 70% calf crop assumption. We then apply this per-calf cost to estimate statewide wolf management expenses, using the study’s finding that 58% of ranchers in wolf-occupied counties experience wolf-induced stressors. Based on these assumptions, ranchers nationwide spend over $60 million each year on efforts to mitigate the impacts of gray wolves (Figure 5).

Importantly, these costs are often incurred even when wolves are not actively present in a given season. The mere threat of predation, and the uncertainty it creates, forces ranchers to implement precautionary strategies year-round, consuming labor and resources regardless of actual wolf activity.

These growing management burdens add another layer of economic strain to ranching in wolf-occupied regions, costs that, while harder to quantify than a dead calf, accumulate quickly and erode the long-term sustainability of the operation.

Putting it All Together

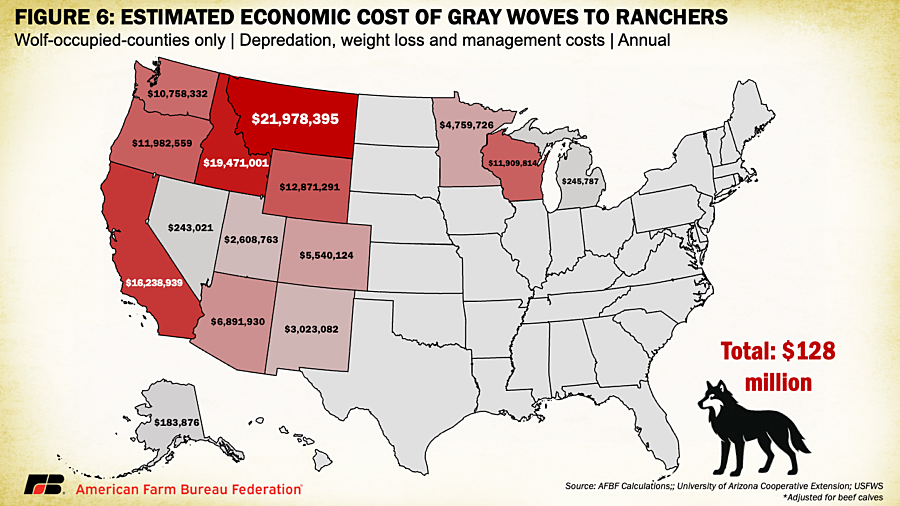

All combined, on a ranch experiencing a modest 2% calf depredation and 3.5% weight loss that also spends the average reported amount on conflict avoidance, annual ranch revenues are reduced by 28% ($34,642). These combined costs, reflecting $128 million in annual costs to U.S. ranchers, are displayed in Figure 6.

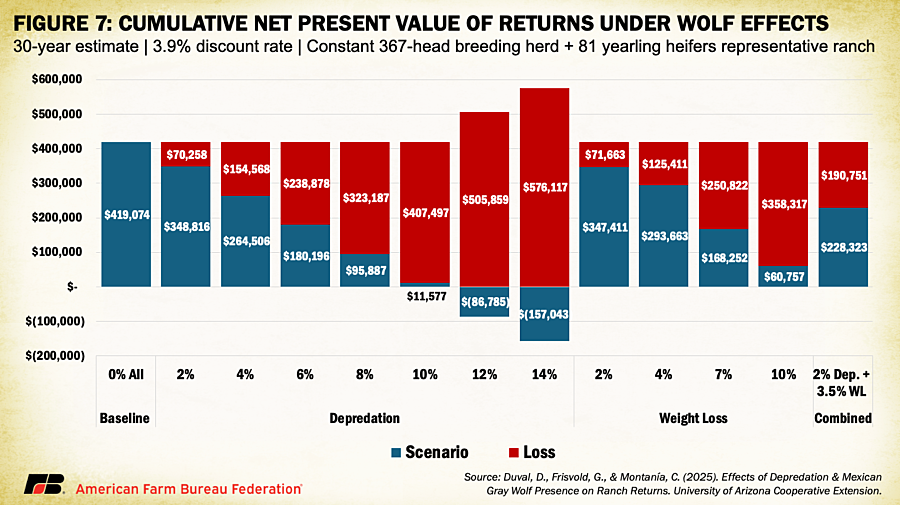

The University of Arizona study also didn’t just look at one year, it projected what repeated losses from wolves would do to a ranch’s profitability over 30 years. Even a moderate level of impact: losing 2% of calves and 3.5% lower weights would reduce the ranch’s net present value by over $191,000. In plain terms, that’s a 45% drop in the ranch’s long-term earning potential. The study estimates that, without wolf impacts, the ranch would generate about $420,000 in long-term profits (in today’s dollars). With average wolf-related losses, that shrinks to $228,000.

While a single year’s loss might seem manageable, the effects compound over time; smaller calf crops mean fewer replacements and fewer animals to sell, while lower weights reduce revenue year after year. These cumulative impacts ripple through herd management and finances, steadily eroding profitability and increasing the odds that the operation may not be financially sustainable in the long run.

Compensation Gaps and Conclusions

While many states and federal agencies offer compensation for confirmed livestock losses due to wolves, ranchers report persistent challenges in accessing these programs. Verifying a depredation requires finding the carcass quickly, often in remote or rugged terrain, and meeting strict evidence thresholds that can be hard to satisfy, especially when scavengers disturb remains. In the University of Arizona study, 55% of surveyed ranchers said they had experienced at least one wolf depredation that went uncompensated.

Additionally, when depredation does occur, the process of locating carcasses, coordinating investigations and filing paperwork for compensation (if available) can require six to 10 hours per incident — resources often uncompensated and undervalued. For some ranchers, the effort and uncertainty involved in confirming a depredation make compensation programs not worth pursuing at all.

Until recently, USDA’s Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) reimbursed only 75% of the fair market value of qualifying animals lost to federally protected predators like wolves. Under the newly enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act, LIP has been updated to cover 100% of market value for predation losses. However, the program still fails to account for the broader financial toll ranchers face: lost future production, veterinary expenses for injured animals, stress-related weight loss or the thousands of dollars spent annually on prevention and mitigation. As a result, ranchers are often left absorbing the bulk of the financial impact of policies shaped far beyond their fenceposts.

That’s the heart of the issue. For many ranching families, the return of wolves is not just a wildlife management question, it’s a daily reality shaped by decisions made in distant urban centers, often by voters and officials who will never have to look into the eyes of a mother cow searching for her calf. Ranchers are the ones bearing the real-world costs of policies shaped far from the range. And they’re doing so while continuing to care for livestock, steward the land and feed a growing world.

If predator recovery efforts are to be economically sustainable, they must be accompanied by policies that recognize the people on the front lines: those whose livelihoods now depend not only on their animals, but on a system that values and supports the cost of coexistence.