ELRP Expands to Support Livestock After Floods and Fires

photo credit: Texas Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

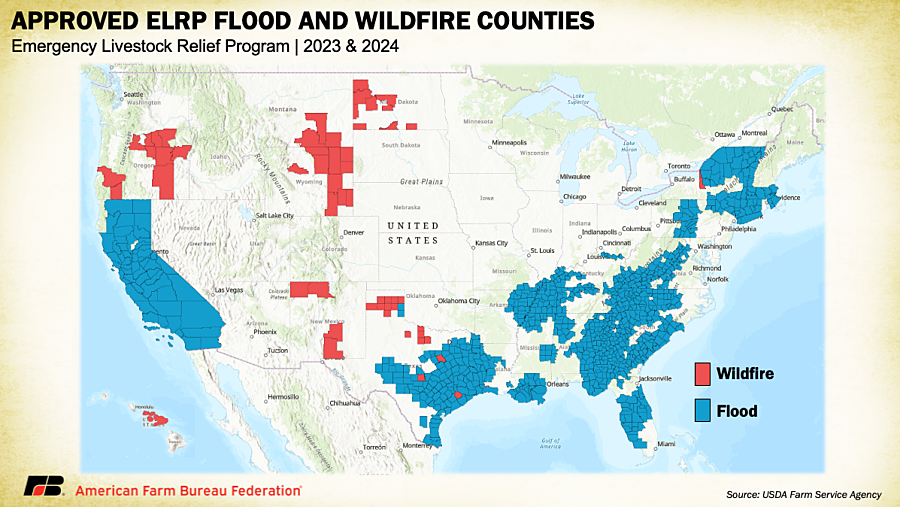

Livestock producers hit by wildfires on non-federal land and floods in 2023 and 2024 now have access to a new source of relief. USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) has opened the application window for the Emergency Livestock Relief Program (ELRP) 2023 and 2024 Flood and Wildfire (FW), with applications due Oct. 31, 2025. Unlike the drought and federal lands wildfire assistance announced earlier this year, this program requires farmers to file directly to apply. Payments will help offset the sharp rise in supplemental feed costs that followed widespread flooding, flash storms and destructive wildfires that upended cattle and dairy operations across much of the country.

Authorized under the American Relief Act of 2025, the FW program deploys roughly $940 million, which is the remaining balance of Congress’s $2 billion livestock disaster assistance directive. While no program can fully cover losses tied to disasters of this magnitude, ELRP-FW provides critical support for ranchers and farmers struggling with damaged grazing land, higher transportation costs and reduced livestock productivity.

Storms, Fires and Economic Fallout

Severe floods and wildfires in 2023 and 2024 created major obstacles for livestock growers across the country. These disasters upended forage conditions, damaged infrastructure and sharply raised feed costs, leaving farmers and ranchers with mounting expenses at a time of already pressured margins.

In both years, wildfire activity scorched nearly 11.5 million acres nationwide. The most severe event came in March 2024, when five fires tore through the Texas Panhandle where over 1.1 million acres were burned, hundreds of structures and fences destroyed and more than 7,000 head of cattle killed.

At the same time, unprecedented floods swept across much of the country. In 2023, California was hit hard by atmospheric rivers, while in 2024 hurricanes Helene and Milton inundated the Southeast. Persistent rains also flooded the Northeast and Midwest, washing out roads, cutting off feed supplies and damaging cropland.

For livestock producers, the economic consequences were swift and severe. Transportation costs soared as washed-out infrastructure delayed feed shipments. Replacement feed was more expensive and harder to find, with crop failures adding to shortages. Dairy and beef operations alike saw reduced performance: lower milk yields, lighter calf weaning weights and ration imbalances caused by sudden shifts in feed quality. These cascading effects underscore why Congress carved out specific funding for disasters that fall outside the reach of the Livestock Forage Program (LFP).

How the Program Works

ELRP-FW provides compensation for increased supplemental feed costs caused by qualifying floods or wildfires occurring on non-federally managed land. Unlike the drought portion of ELRP, which used existing LFP records to automatically deliver payments, this program requires farmers to apply directly using form FSA-970.

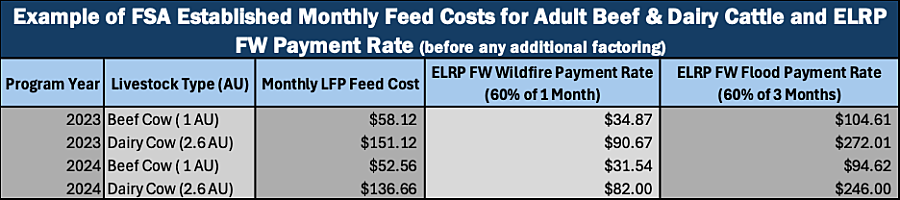

Payments are based on USDA’s standard monthly feed cost estimates per animal unit. For flood-related losses, assistance covers 60% of three months of feed costs. For wildfires on non-federal land, assistance equals 60% of one month of feed costs. These rates reflect the longer recovery needed for flood-damaged land compared to land burned by fire.

Eligibility

Eligibility is broad but clearly defined. To be eligible, farmers must have owned, leased, purchased or been under contract to raise eligible livestock on the start date of the qualifying disaster. They must also demonstrate that the disaster event led to increased supplemental feed costs.

Covered livestock include beef and dairy cattle, beefalo, buffalo, bison, sheep, goats, alpacas, llamas, deer, reindeer, elk, equine, ostriches and emus. Livestock in commercial feedlots, auction facilities or operations that buy and resell animals without sharing in the production risk are not eligible.

FSA has already confirmed qualifying floods and wildfires in many counties using disaster declarations, weather data and economic reports. In these counties, growers will not need to supply event documentation. For counties not pre-approved, farmers can still qualify by providing acceptable evidence such as photos, insurance documents or local/state emergency declarations.

Application Process

Because USDA cannot rely on LFP records for this track, producers must submit a new application by October 31, 2025. Applicants will need to file:

- FSA-970 (ELRP-FW application form) for each program year affected.

- Livestock inventory records as of the disaster date.

- Disaster event documentation, if not in a pre-approved county.

- Farm record updates to verify physical location of livestock, if necessary.

- Contract grower agreements, if applicable.

Supporting eligibility forms (CCC-901: Farm Operating Plan, CCC-902: Member Information for Legal Entities, AD-1026: Highly Erodible Land Conservation and Wetland Certification, and FSA-510: Exemption to the $125,000 payment limit if seeking higher limits) must be on file by November 2, 2026. Producers impacted in both 2023 and 2024 must apply separately for each year.

This structure ensures that those who bore the costs of buying extra feed are documented and compensated, even when the disaster event was outside of LFP’s scope.

Payment Calculation

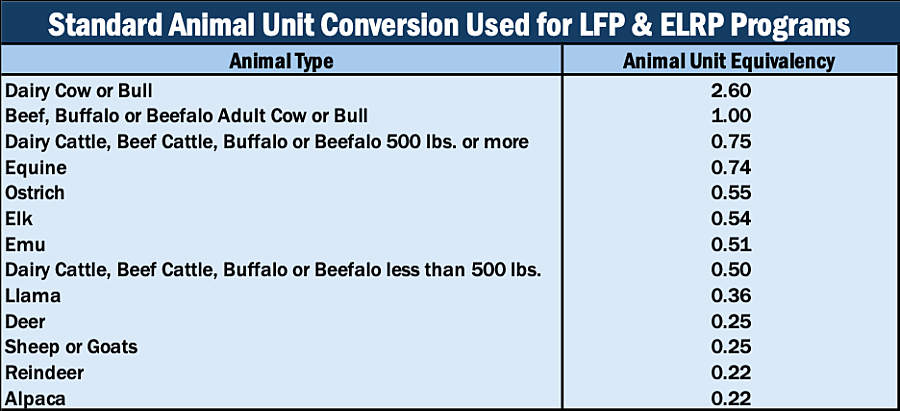

Payments are built on the same animal unit (AU) framework as LFP. One base AU is defined as a mature 1,000-pound cow with or without a calf. Conversion rates adjust feed costs for other livestock types, such as 2.6 AUs for a dairy cow or 0.25 AUs for sheep or goats.

USDA calculates ELRP-FW payments by multiplying the number of eligible livestock by the AU conversion rate, then by the relevant monthly feed cost, then by the disaster factor (three months for floods, one month for wildfire), applying the fixed 60% rate and finally applying a national payment factor if demand exceeds the $940 million available (to be determined).

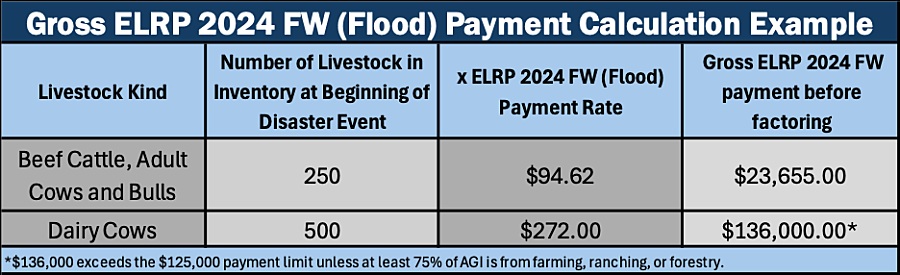

For example, a rancher with 250 beef cows in Alleghany County, North Carolina, directly impacted by Hurricane Helene’s flooding in 2024 would start with USDA’s monthly feed cost of $52.56 per AU. Three months equals $157.68, and applying the 60% rate produces $94.62 per head. Across 250 cows, the gross payment equals $23,655, before additional factoring. Likewise, a dairy farmer with 500 dairy cows in Sonoma County, California, directly impacted by atmospheric river flooding in 2023 would start with USDA’s monthly feed cost of $58.12 times 2.6 AU for dairy cows ($151.12). Three months equals $453.36, and applying the 60% rate produces $272.01 per head. Across 500 cows the gross payment equals $136,000 before any additional factoring.

ELRP-FW applies the same payment limitation structure as the drought/federal wildfire track of ELRP. For each program year (2023 and 2024), total assistance across both ELRP components is capped at $125,000 per producer. Producers who derive at least 75% of their adjusted gross income from farming, ranching or forestry may qualify for a higher cap of $250,000, provided they submit Form FSA-510 with supporting documentation. So, unless this dairy farmer certifies that at least 75% of their adjusted gross income comes from farming, their payment would be capped at the standard $125,000 limit once factoring is applied.

This formula ensures that payments are tied to standardized feed cost benchmarks rather than requiring producers to reconstruct receipts months or years after the event. It is also intended to balance fairness across regions, livestock types and disaster types.

Looking Ahead

FSA projects potential program demand of $2.45 billion, nearly three times the available funds (about $1.01 billion for 2023 floods, $1.08 billion for 2024 floods, $17 million for 2023 wildfires, and $120 million for 2024 wildfires). With such a gap, factoring is inevitable. USDA expects most payments to be issued in fiscal year 2026, after the close of the application window and the establishment of a national payment factor.

While ELRP-FW will not make producers whole, it represents a meaningful step toward stabilizing ranches and dairies hit hardest by floods and non-federal wildfires. By covering a share of supplemental feed costs, the single largest expense category for most operations during a disaster, the program offers critical breathing room. For ranchers staring at destroyed hay reserves, impassable roads or scorched pastures, that bridge can mean the difference between rebuilding and liquidation.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL