European Union Deforestation Rule: Creating Administrative Hurdles and Market Barriers Rather than Saving Forests

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

Key Takeaways

- The EU fails to recognize the long-standing position of American farmers and ranchers as global leaders in sustainable agricultural production. While designated as low risk for deforestation, American producers are still constrained by intense traceability and validation requirements.

- Commodity supply chains do not have traceability structures in place for compliance with EUDR. The commodities covered under EUDR are not vertically integrated in the U.S., so there will be significant hurdles to supply geolocation data from each step of the supply chain to another.

- EUDR has once again been delayed in enforcement until 2026. However, as long as the rule stands as currently drafted, agricultural supply chains will be strained attempting to comply before the deadline.

The European Union (EU) passed a deforestation rule (EUDR) in June 2023 requiring imports of cattle, wood, cocoa, soy, palm oil, coffee and rubber, and any products produced with them, to prove they did not originate from land that was deforested or degraded after 2020. While cattle is the listed covered commodity, beef and beef cattle are the only affected products as dairy and veal, significant European markets, were given exemptions. EDUR was originally developed to combat the destruction of tropical rainforests, largely through expansion of Brazilian agricultural production. Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research reported that over 1.5 million acres of the Amazon Rainforest were deforested between August 2023 and July 2024, with 80% of that for cattle pastures.

However, American farmers are being swept into significant traceability and compliance hurdles for one of their major trading partners. EU officials have once again delayed enforcement of the rule until the end of 2026 due to concerns over the rule’s complexity, but anticipation of EUDR has caused significant trade barriers for American farmers, ranchers and foresters.

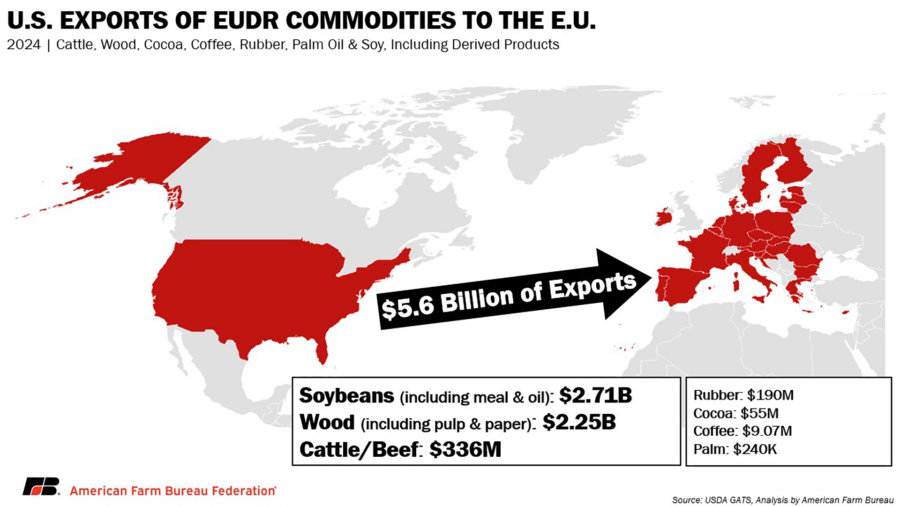

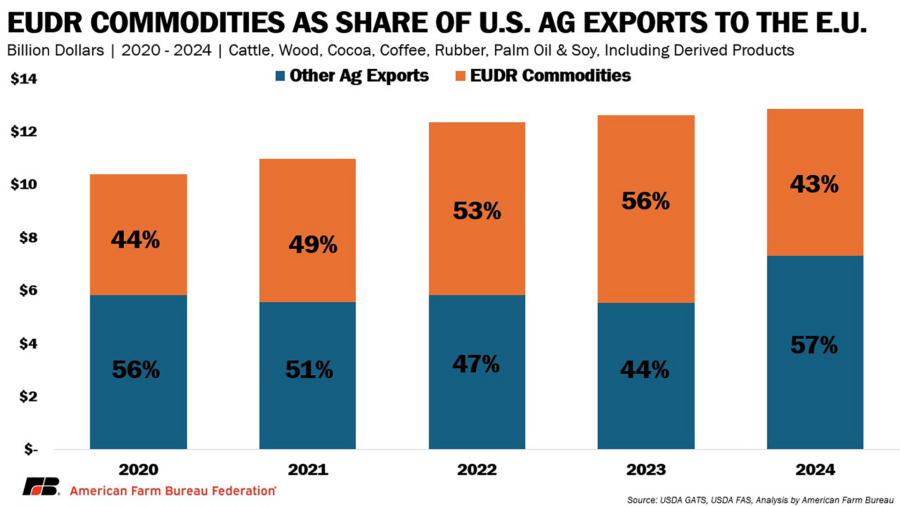

The Impact of EU Trade

As the 4th largest export market for U.S. commodities, EU regulations can have significant impact on American production, particularly on industries with a high volume of export sales to member countries. Of the commodities covered under EUDR, the EU is the 2nd largest market for U.S. soybeans, 4th for forest products and 8th for beef. All seven covered commodities account for nearly $5.6 billion, almost 44% of the total $12.85 billion in U.S. agricultural exports to the European Union in 2024. However, trade of these covered commodities has decreased 15% from 2022 to 2024 after the rule was passed, even without implementation, while overall agricultural exports to the EU have increased 4% in the same time period.

Traceability Troubles

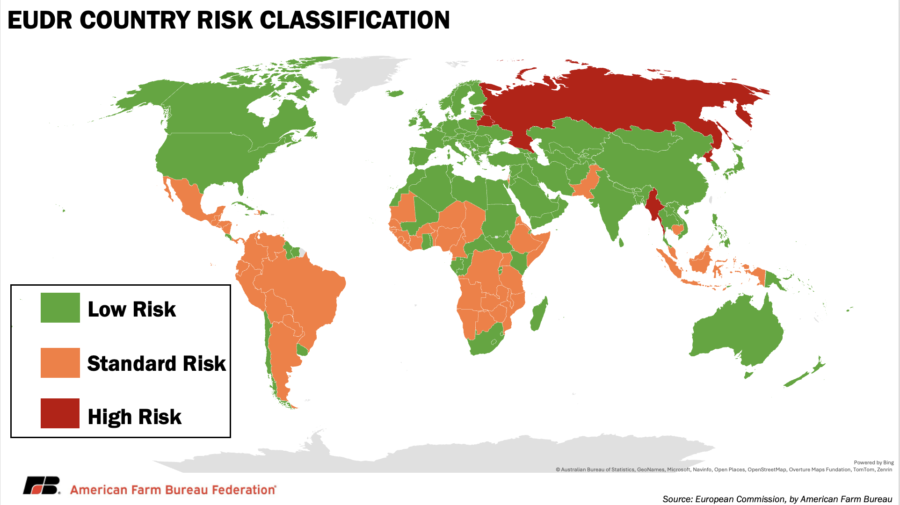

The core of EUDR revolves around being able to prove that each plot of land used to produce EU imports was not recently in forestland. The United States is classified as “low-risk,” and therefore unlikely to import products linked to deforestation. This cuts down on the number of inspections U.S. businesses are subject to, but it does not erase the extensive data and traceability requirements required to ensure compliance. Interestingly, despite being recognized as a major deforester, Brazil is only categorized as a standard risk and also have less stringent compliance checks, largely due to government tracking of the issue rather than actual prevention of deforestation.

Commodities imported to the EU under the deforestation rule must provide geographic coordinates to the exact plot of the land the product was produced on. Beyond requiring private proprietary information to be shared with numerous business entities and government agencies with little oversight from the owner of the property, this also proves logistically challenging for numerous reasons.

First, bulk commodities such as soy are mixed with other fields and even producers in storage facilities. Products like soybean meal or wood chips are also by-products of other production measures, so will mix an even greater amount of individual farmer products together to produce an export volume. Ensuring that each shipment accurately reflects the location of each field input into the shipment will require advanced supply chain monitoring throughout harvest, transport, storage and purchasing. Particularly as the commodities covered under EUDR are largely not vertically integrated in the U.S., there will be significant hurdles to supply geolocation data from each step of the supply chain to another. Particularly when farmers themselves may not know where their product is going once it leaves the farm, they may be unaware of the traceability requirements, or being doing additional administrative tracing that is not ultimately needed.

Second, field sizes can vary widely. The EU considers a “plot” to be the real estate property where the commodity was grown. This can range from an entire ranch in the western United States, to small patchwork fields of soybeans that were each purchased or rented as parcels in the Southeast. Farmers and ranchers will have varying levels of record keeping on their own operations to ensure they can provide purchasers with necessary information depending on the geographical makeup of their farm. If farms purchase or sell land, they will also have to add in administrative time to adjust their geolocation data for export purchasers. Particularly for small farms without extensive administrative teams or tracking, these additional traceability requirements may require outside assistance at high costs.

A Hit to U.S. Foresters

The ambiguity in defining production “plots” has significant impacts for foresters. Products are classified as having been produced on deforested land if any of the land on the property has been converted to cropland. When plots can contain the entirety of a farm, foresters who may rotate their plots of forestland are penalized as deforesting even if they replant trees elsewhere on the property. Foresters are also subject to additional scrutiny of forest degradation, despite limited guidance on what the EU will consider degradation, or recognition of best management practices for forestry land.

Conclusion

The EU Deforestation Rule has already caused supply chain hurdles for American farmers, ranchers and foresters, and the rule has not even begun being enforced. EU farmers themselves have raised concerns over their compliance requirements and received additional flexibilities, and member governments are still navigating how to implement the complex auditing system. With these logistical challenges clear even to EU officials, the European Commission has voted to once again delay the rule’s implementation until 2026 and 2027 for large and small businesses, respectively. However, as long as the rule stands as currently drafted, agricultural supply chains will be strained from the looming enforcement deadline.

Overall, the EU fails to recognize the long-standing position of American farmers and ranchers as global leaders in agricultural production with environmental stewardship. A rule that was originally targeted to penalize bad actors in the global marketplace has now hindered some of the most productive producers in the world and put up roadblocks for one of the main trade relationships between the U.S. and the EU. Without steps to mitigate impacts, EUDR could easily expand to other commodities and continue to strain trade. As the EU continues to explore methods to reduce nontariff barriers to trade, including EUDR, under the US-EU Framework on Trade, discussions revolve around ways to recognize the lack of deforestation risk in the U.S. by developing a new “negligible” risk category, further cutting down on red tape for American commodities.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL