Small Family Farms, The Roots of American Agriculture

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

When people are asked what a “small farm” is, they may base their answer on the number of acres or number of animals a farm has – and they often assume that there aren’t many of them. However, small, family-owned farms continue to dominate the makeup of American farms and ranches across the country.

USDA considers any place that has at least $1,000 of agricultural product sales as a farm. The Census of Agriculture reports 25% of farms with no sales in any year, and 30% with less than $10,000 in sales. Regardless, these farms are important community members and may be contributing to the local food system. With such variation in farm size and structure nationwide, USDA considers small farms as those with less than $350,000 of gross cash farm income (GCFI), regardless of whether the owner’s primary job is farming.

It’s important to note that GCFI, discussed in detail below, is not a measure of profit. Recent forecasts of net farm income show warning signs for farmers nationwide. Even with projected rebounds in 2025, crop receipts are expected to decline while livestock gains only partly offset rising costs. For small farms that already operate on thin margins, these trends highlight just how challenging it can be to keep operations viable year after year.

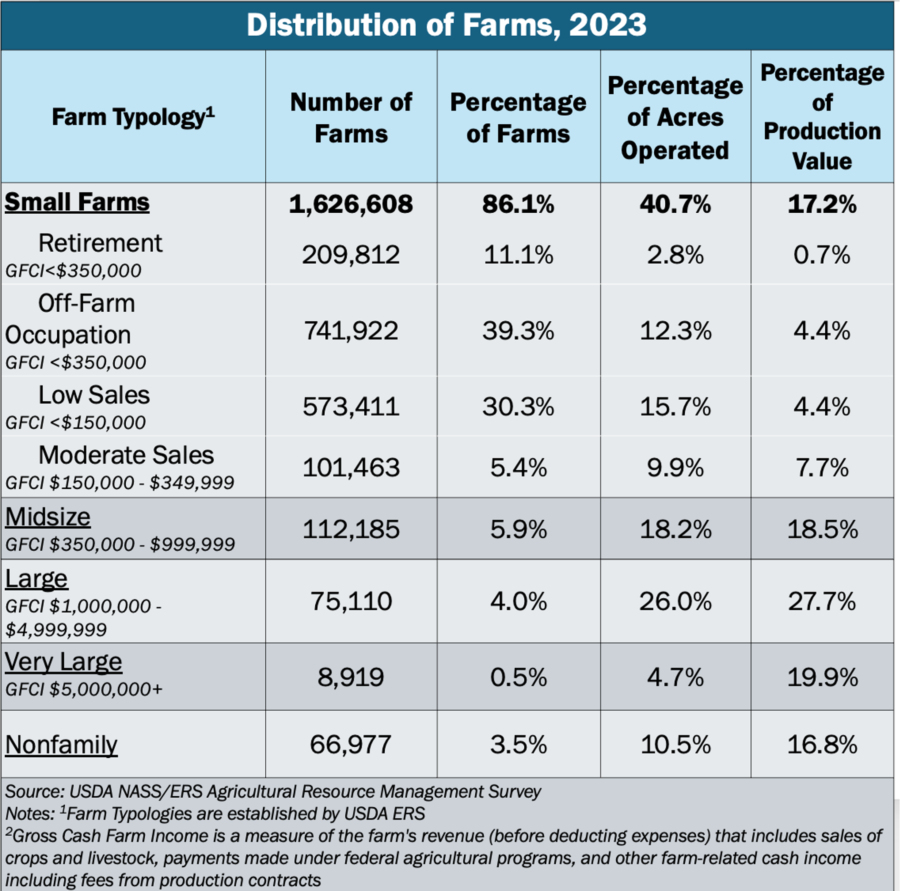

By Revenue

USDA classifies farm size based on GCFI, which includes sales of crops and livestock, payments made under federal agricultural programs, and other farm-related cash income including fees from production contracts. Family farms are split into small, midsize, large and very large farms depending on how much GCFI they generate in a year. To be considered small, a farm must pull in less than $350,000 a year. More than 86% of the 1.9 million farms in the U.S. are considered small family farms based on this classification.

Small farms are further subdivided based on the primary farmer’s job. The majority of farms earn income off the farm to support farming activities – 77% of total U.S. farm household income came from off-farm jobs. The largest category of farms in the U.S. are those small farms where the farmer’s main job is not farming, making up 39% of farms.

The second-largest group of U.S. farms is considered “low-sales” farms. These are farms where the operator’s main job is farming, but their farm brings in less than $150,000 of GCFI a year. This group includes more than 30% of all farms in the country. And rather than making money, these families actually lose an average of $5,725 each year from farming after expenses, which average $28,550 per family farm.

When people hear that a “small” farm can have $350,000 in GCFI, it can sound like the farm family is taking home a big salary. But that number is not comparable to wages or salaries. It is simply the farm’s total revenues before subtracting the massive expenses that come with producing food. Seeds, feed, fuel, fertilizer, equipment, land payments, insurance and hired labor can easily run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, often leaving little-to-no profit. USDA estimates that average production expenses in 2022 were $274,794 for small family farms with GCFI between $150,000 and $349,999. After expenses, these farms earn only $44,753 from farming on average.

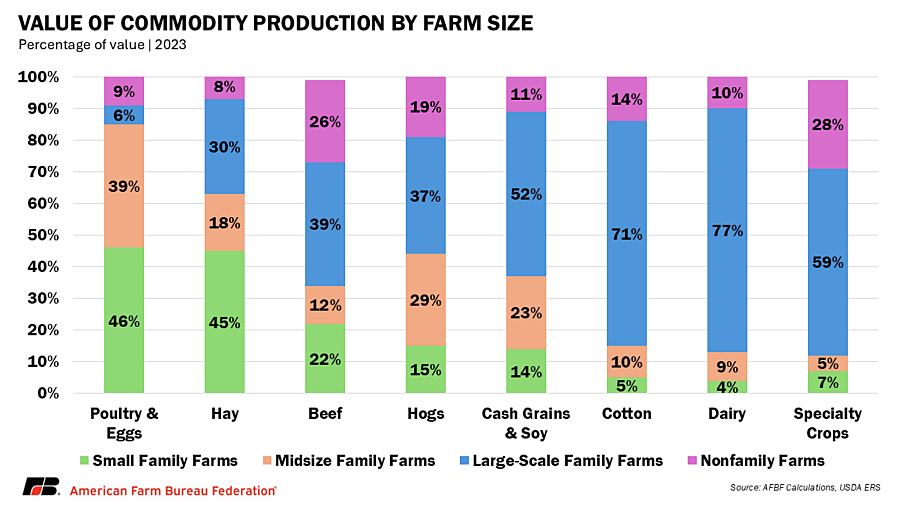

The type of farming may in itself also impact how a farm is classified due to the value of the crop. Specialty crops are high value and require significant up-front investments in things like infrastructure or long-lasting plants, bushes or trees. In 2023, the average specialty crop farm faced $466,400 in cash expenses, compared to $179,300 for the average U.S. farm. That means specialty crop growers carried expense levels about 160% higher than the typical farm. As such, only 7% of specialty crops are grown by small farms (by this definition), both due to higher prices received and scale required to meet costs. Cash grains and other row crops in the United States are also typically grown with highly technical equipment, so economies of scale again increase average farm size to cover the cost, pushing small farms to only 14% of cash grain and soybean production value.

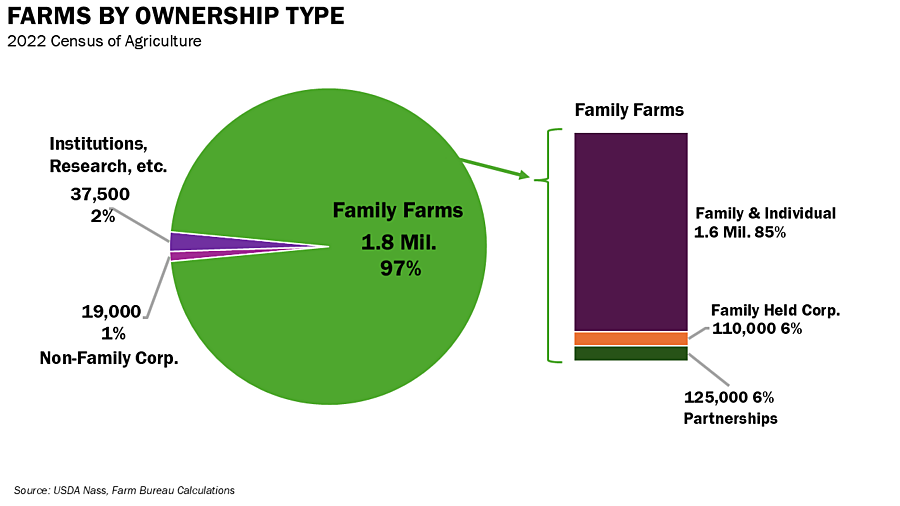

Farm Ownership

Nearly 97% of American farms are owned by families. While it’s often thought that large “corporate” farms are not family owned, less than 1% of all farms are non-family-owned corporations. Families may choose to legally organize their businesses as corporations for tax purposes, and 6% of farms nationwide are corporations that are exclusively held by families, some of which are still small based off income or acreage.

Just because a farm is family owned, it does not mean that it is instantly small. Ten percent of farms are owned by families that generate more than $350,000 in farm revenues. However, small family farms still make up the majority of farms nationwide and operate a higher share of acres altogether than any other farm size.

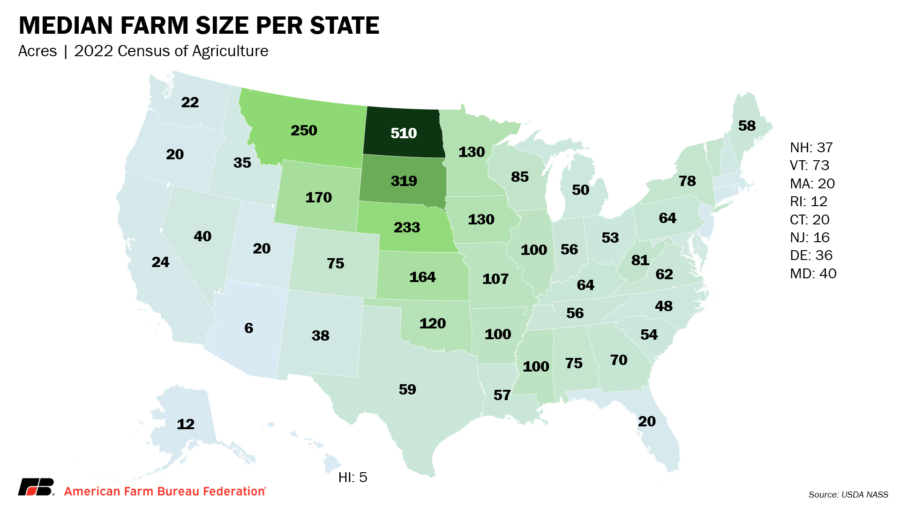

By Acreage

The average American farm was 466 acres in 2024, only 26 acres more than in the 1970s. When you examine the median size – where half of farms are larger and half are smaller, eradicating any skew from a few very large or very small farms – the typical American farm was only 72 acres in the 2022 Census of Agriculture. In fact, 42% of all farms are smaller than 50 acres. This wide gap between the average and median underscores how a relatively small number of very large farms pull up the average, while most farms operate on a much smaller scale. Farm size also varies greatly by region: row crop farms in the Midwest and Plains are often larger, while farms in the Northeast and Southeast are typically smaller and more diversified.

Small farms may be ideal for livestock production, direct-to-consumer marketing or subsistence farming. Small farms contribute 46% of production value of poultry and eggs, which can be produced on smaller acreages and sold in local communities. They also make up larger shares of production in hay and beef than other sectors, which may further reflect local market opportunities.

Conclusion

Small family farms remain the roots of American agriculture, not only because they represent the overwhelming majority of farm operations, but also because they embody the resilience and determination that keep rural communities thriving. Yet, farming at any size or scale is cost-intensive, yet rising input prices, thin margins, global competition and limited access to new technologies put significant pressure on small farms. On top of these economic challenges, small farms often face the same regulatory requirements as larger operations, but without the scale to spread compliance costs across more acres. This helps explain why farms continue to grow in size as families expand to cover rising costs.

Small farms also sustain rural communities beyond the farm gate. Because they make up most U.S. farms and the farmers who run them often work off the farm, their households provide much of the population and workforce that keep schools, hospitals and local businesses open. Without them, many rural communities would struggle to maintain the services that make them viable places to live and work. While many families of all sizes rely on off-farm income to sustain their way of life, small farms’ importance is undeniable as they face losses but continue to contribute to the food, fiber and fuel supply chain. Continued recognition and support for farms of all size, but particularly those small family farms that define the American countryside, is critical to ensuring agriculture remains competitive and supports rural communities.