Alfalfa in the Red: Rising Costs, Falling Returns

TOPICS

Alfalfa

photo credit: AFBF

Daniel Munch

Economist

Key Takeaways

- A major U.S. field crop without a safety net: Alfalfa is the fourth most valuable field crop in the U.S., generating roughly $8.1 billion in farm-gate value in 2024, yet it remains largely outside core farm safety-net programs.

- Prices collapsed while costs stayed high: After record prices in 2021–2022, alfalfa prices fell more than 40%, while production costs remained elevated, pushing average returns into negative territory since late 2023.

- Export demand has weakened sharply: Shipments to key markets, especially China, have fallen amid global dairy market shifts and ongoing trade conflicts, reducing a critical outlet for Western hay producers.

- Losses are large with limited relief: Estimated 2025 economic losses total roughly $2.9 billion, or about $203 per acre, with no access to commodity support or the Farmer Bridge Assistance Program.

Alfalfa is a core input into U.S. dairy and beef production and one of the country’s most economically significant crops. In 2024, it ranked as the fourth most valuable field crop, generating an estimated $8.1 billion in farm-gate sales, behind only corn, soybeans and wheat.

In recent years, alfalfa producers have faced a sustained deterioration in margins, driven by a combination of weather-related production volatility, persistently high input costs, shifting international livestock feed demand and heightened export uncertainty. Unlike many other major crops, alfalfa has limited options to offset losses when prices fall, as available risk management tools are narrowly focused and do not address broader margin pressures.

Those pressures are now reflected clearly in returns. Prices spiked during the drought-driven supply tightening of 2021–2022, but that rally reversed as weather conditions improved and export demand weakened. With prices now below full economic cost in many regions, losses have widened — and alfalfa is not eligible to receive to payments from the recently announced $11 billion Farmer Bridge Assistance Program, leaving the sector’s current shortfall unaddressed.

Production Dynamics Shape Risk

Unlike annual crops that are terminated every year, alfalfa is a perennial legume grown in multi-year “stands,” where a single planting supports repeated harvests over multiple seasons. Fields are typically harvested repeatedly for five to seven years or longer, depending on management, weather and water availability. In rain-fed regions such as the Midwest and upper Plains, growers commonly take three to four cuttings per year, while irrigated systems in portions of the West and Southwest can support seven or more cuttings annually.

This long stand life limits how quickly production can respond to market signals. When prices rise, new seedings represent only a small share of total acreage, and newly planted stands often take one to two years to reach full productivity. Conversely, when prices fall, growers may remain locked into production even as margins deteriorate. The result is a supply base that adjusts far more slowly than most annual crops.

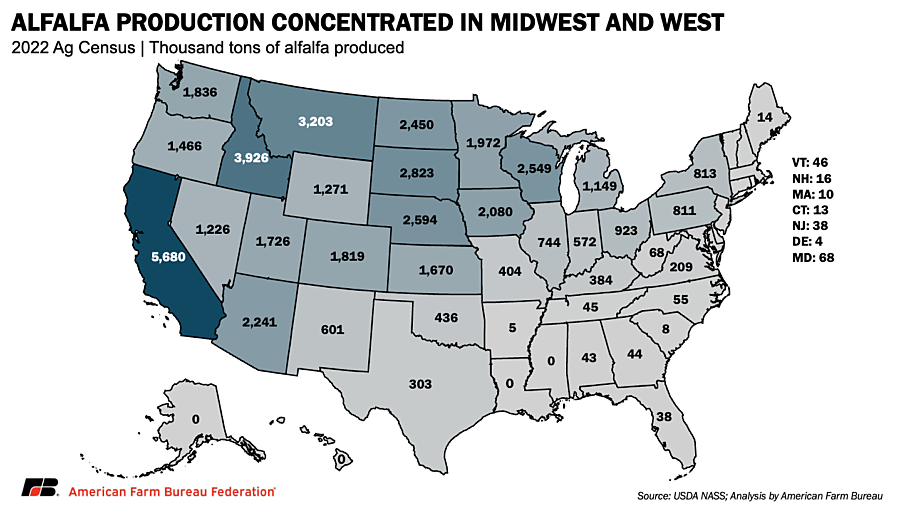

Geographically, alfalfa production is widespread but concentrated in regions with strong dairy and cattle sectors and more favorable growing conditions. California, Idaho, Montana, the Dakotas and Arizona consistently rank among the top producing states, achieving high yields due to longer growing seasons and irrigation.

Nationally, alfalfa acreage has declined for decades. From 2000 to 2025, harvested acres fell by nearly 40%, dropping from roughly 23 million acres to about 14 million. Part of this decline reflects land competition from crops with more favorable economic returns, especially crops eligible for commodity safety net programs such as Price Loss Coverage (PLC), Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and marketing loans, as well as those benefiting from biofuel-driven demand that has periodically lifted prices over the past two decades.

Drought and Weather Volatility

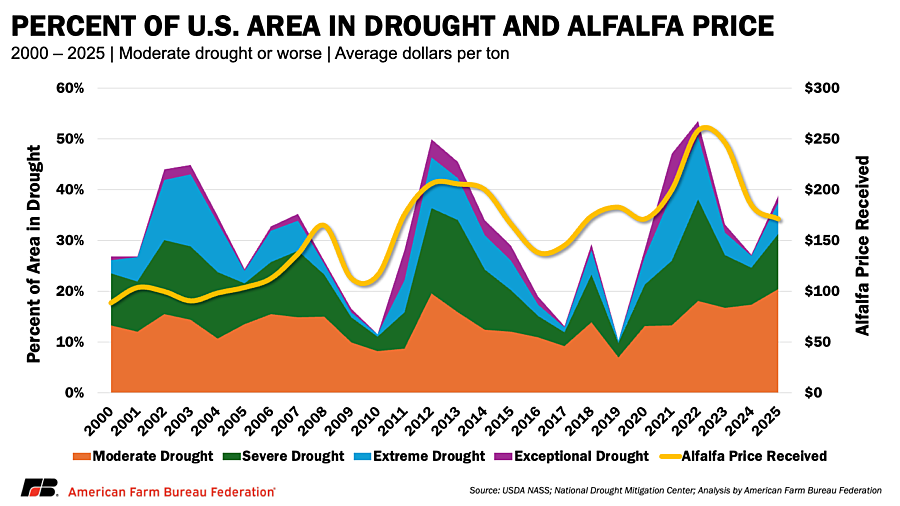

Weather has been one of the most persistent headwinds alfalfa growers face. From 2020 through 2022, the U.S. experienced one of the most geographically widespread drought periods on record. According to the drought monitor, by early 2023, growers had endured 119 consecutive weeks with at least 40% of the contiguous U.S. in drought, and in October 2022, over 60% of the country was classified as abnormally dry or worse.

For alfalfa, drought reduces both yield and quality, while water shortages in irrigated regions can force acreage out of production entirely. In California and Arizona, curtailed surface-water deliveries and tightening groundwater regulations led some growers to fallow alfalfa acres during 2021–2022, contributing to the lowest U.S. hay inventories recorded since 1954, tightening supplies and placing upward pressure on hay prices.

Drought also intensified demand in the hay market. According to our surveys of drought-impacted farmers and ranchers in 2021 and 2022, 70% to 80% of respondents reported removing animals from rangeland due to insufficient forage, increasing reliance on hay. Nearly 90% reported higher local feed and forage costs, and more than 70% traveled long distances to secure feed. For many cattle operations, these conditions translated into emotional structural adjustments: 66% of respondents reported herd liquidations, decisions that continue to influence the U.S. cattle herd’s ability to recover. As a result, weather-driven supply shocks tend to produce sharper and more persistent price movements, with pronounced price spikes during drought years, followed by softening as weather improves and inventories gradually rebuild.

Trade Volatility

Exports have become a critical, and increasingly volatile, outlet for U.S. alfalfa, particularly for Western producers. Roughly 31% of West Coast alfalfa and other hay production is exported, compared to about 3% of total U.S. hay output nationally, leaving Western growers especially exposed to shifts in global demand.

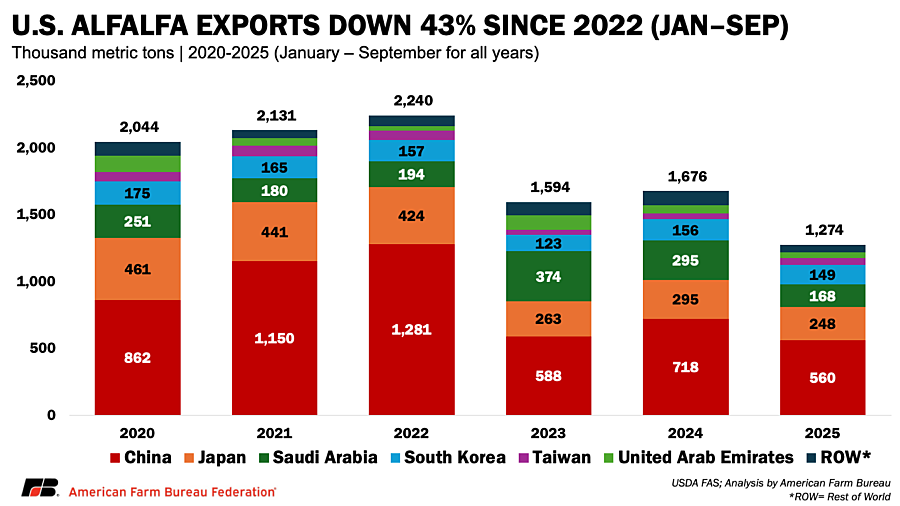

Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Taiwan have long served as key destinations for U.S. alfalfa, particularly for premium dairy-quality hay. Since 2012, however, China has consistently ranked as the largest foreign buyer by volume, driven by rapid expansion of its dairy herd and efforts to improve milk yields through higher-quality feed. In 2022, China purchased approximately 1.66 million metric tons, accounting for 57% of total U.S. alfalfa hay exports and playing an outsized role in supporting Western hay prices.

That export channel has weakened sharply. After reaching a record 2.88 million metric tons in 2022, total U.S. alfalfa hay exports fell to about 2.18 million metric tons in 2023, a 23% year-over-year decline and the lowest level in a decade. The contraction was driven overwhelmingly by China, where imports of U.S. alfalfa fell 47%, dropping to 870,000 metric tons. Softer Chinese milk prices combined with an oversupplied domestic dairy sector and broader economic slowdown, reduced feed demand and curtailed purchases.

This pullback continued into 2024 and 2025. Between January and September, China imported 1.28 million metric tons of U.S. alfalfa in 2022, compared to 718,000 metric tons in 2024 and just 560,000 metric tons in 2025, the lowest level since 2020. Ongoing U.S.–China trade tensions and inspection-related frictions have added further uncertainty to what was once the most reliable export market.

Other markets have provided only partial and uneven offsets. Saudi Arabia’s imports surged in 2023, rising roughly 42% to about 431,000 metric tons, as domestic water-conservation policies sharply curtailed local forage production. However, shipments to Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern buyers softened through 2024 and into 2025, as procurement strategies shifted and buyers adjusted inventories following the 2023 surge. The UAE followed a similar pattern, with imports jumping more than 250% in 2023 from a low base but failing to sustain that pace in subsequent years. Japan’s imports of U.S. alfalfa declined sharply in 2023 and remained subdued in 2024–2025, as a strong U.S. dollar reduced price competitiveness and buyers increasingly sourced from alternative suppliers or relied more heavily on domestic forage. Together, these trends underscore that gains in select markets have not been sufficient or durable enough to offset the contraction in Chinese demand.

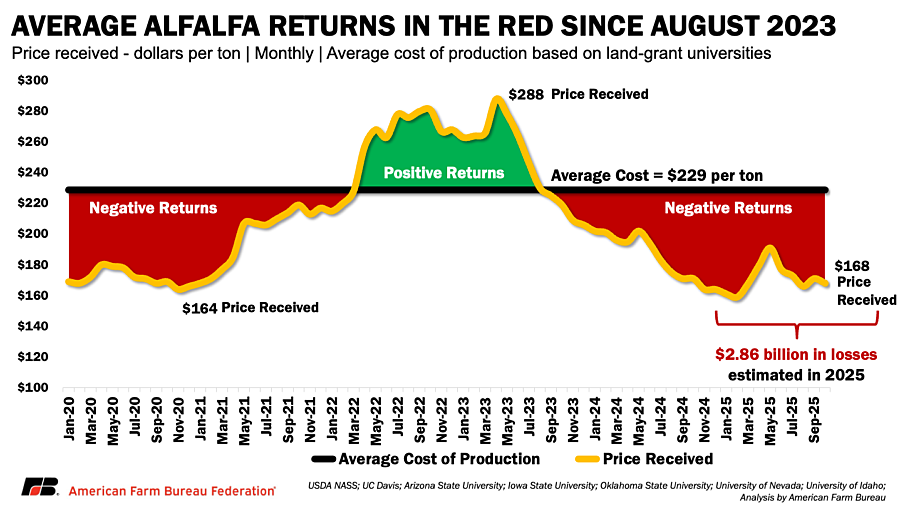

Prices Fall as Costs Stay Elevated

The financial impact of these combined pressures is now evident in returns. Alfalfa prices peaked during 2021–2022 amid drought-driven shortages, but the rally proved short-lived. From April 2023 to November 2024, national average prices fell from about $288 per ton to $164 per ton, a 43% decline. By 2025, prices averaged roughly $171 per ton, well below recent break-even levels.

At the same time, production costs have remained stubbornly high. University cost-of-production studies across the Plains and Western states show full economic costs ranging from $165 to more than $300 per ton, depending on irrigation intensity, yield and region. Input expenses, particularly water, fertilizer, labor, fuel and machinery, have climbed 20% to 35% since 2020, while yields have stagnated near 3.5 tons per acre.

Estimated 2025 Economic Losses

Cost-of-production studies from the University of California (2020),University of Arizona (2023), Iowa State University (2025), Oklahoma State University (2024), University of Nevada (2008-indexed) and the University of Idaho (2020) show that alfalfa production carries an average full economic cost of about $229 per ton, a figure that reflects operating expenses, cash overhead, and the annualized non-cash costs of land, equipment and field establishment. Together, the states represented by these university budgets account for about one-third of U.S. alfalfa production. While some higher-yield operations may cover a portion of variable operating costs, recent prices frequently fail to recover full economic costs, leaving producers unable to fully cover capital recovery and land charges. Using USDA’s estimate of 14.12 million harvested alfalfa acres in 2025 and an average yield of 3.51 tons per acre, total production reached roughly 49.8 million tons, placing the sector’s annual economic production costs near $11.4 billion.

USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service price data show 2025 year-to-date average prices near $171 per ton, generating approximately $8.5 billion in farm-level revenue. The result is an estimated $2.9 billion economic shortfall in 2025, or a loss of about $203 per acre.

Limited Safety Nets and Exclusion from Recent Aid

Despite its economic scale, alfalfa has never been a covered commodity under core farm bill commodity programs such as PLC and ARC. As a result, alfalfa producers do not have access to price- or revenue-based support when markets weaken, unlike many other major crops.

Some risk management tools are available through the federal crop insurance program, but coverage remains limited and uneven. In certain states, producers can insure alfalfa hay or seed under yield-based policies, though these products are not widely available and do not protect against price-driven revenue losses. A key constraint is the absence of a standardized price discovery mechanism for alfalfa, which limits the feasibility of revenue-based insurance. The most commonly used tool for forage producers is the Pasture, Rangeland and Forage (PRF) rainfall index program, which provides indemnities when precipitation in a selected grid falls below historical averages. PRF is primarily structured to help livestock producers manage forage availability risk rather than to insure market-oriented hay production, and it is not crop-specific or tied to actual yield, quality or market sales. As a result, many alfalfa growers, particularly those producing hay for commercial sale, may view PRF as an imperfect substitute for traditional yield or revenue insurance.

Disaster assistance during recent droughts has also been uneven. Programs such as the Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP) and the Emergency Livestock Relief Program (ELRP) provided payments to livestock producers experiencing grazing losses or elevated feed costs during 2021–2022. For cattle operators who both own livestock and grow alfalfa, these payments may have supported forage use or purchases. However, standalone alfalfa growers without livestock generally did not qualify, highlighting a structural gap between livestock-focused disaster aid and forage producers whose losses stemmed from reduced yields, quality degradation or market disruptions.

Ad hoc assistance tied to trade and pandemic disruptions has provided only modest relief. During the U.S.–China trade dispute, alfalfa was initially excluded from the 2018 Market Facilitation Program (MFP) and later added in 2019 following industry advocacy. While payment rates varied by county, alfalfa payments were typically under $30 dollars per acre, substantially lower than payments received by many row crop producers.

Pandemic-era assistance did increase support but only marginally. Under the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), alfalfa growers were eligible for multiple payments up to $35 per acre each . At typical yields of 4–5 tons per acre, that support translated to roughly $7–$9 per ton, a limited offset against production costs that often exceeded $200 per ton during the same period.

Looking Ahead

Alfalfa’s role in U.S. agriculture is foundational, supporting livestock production, rural economies and export markets across more than 218,000 farms nationwide, according to the 2022 Census of Agriculture. Yet in 2026, growers face a familiar but intensifying challenge: high costs, volatile weather, uncertain trade access and limited policy support. Without more responsive risk management tools and timely assistance, prolonged negative margins risk accelerating acreage loss and undermining long-term supply resilience.

Recognizing alfalfa’s economic importance, alongside other crops facing similar pressures, will be essential as policymakers consider how best to ensure the stability of the broader agricultural system.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL