Agricultural Trade: China Steps Back from U.S. Soybeans

photo credit: AFBF

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

Trade is a hot topic with a lot of uncertainty. Trade policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., will impact farmers and ranchers in the countryside. This Market Intel is part of a series exploring agricultural trade, including the potential impacts of trade policy changes.

International trade has long been a lifeline for American agriculture, providing markets for surplus production and supporting millions of jobs across the economy. For decades, China stood at the center of that story, purchasing tens of billions of dollars in U.S. farm goods and emerging as the largest buyer of American soybeans.

But the trend over the past decade says times are changing. Even when U.S. farmers produce crops that are priced competitively, China has steadily reduced its reliance on the United States, turning instead to Brazil, Argentina and other suppliers. The slowdown of sales in 2025 is not an isolated event: it is part of a longer trajectory in which China is diversifying away from American agriculture. For U.S. farmers, this shift has meant fewer sales, a growing agricultural trade deficit and greater uncertainty about the future role of China as a market for American agriculture.

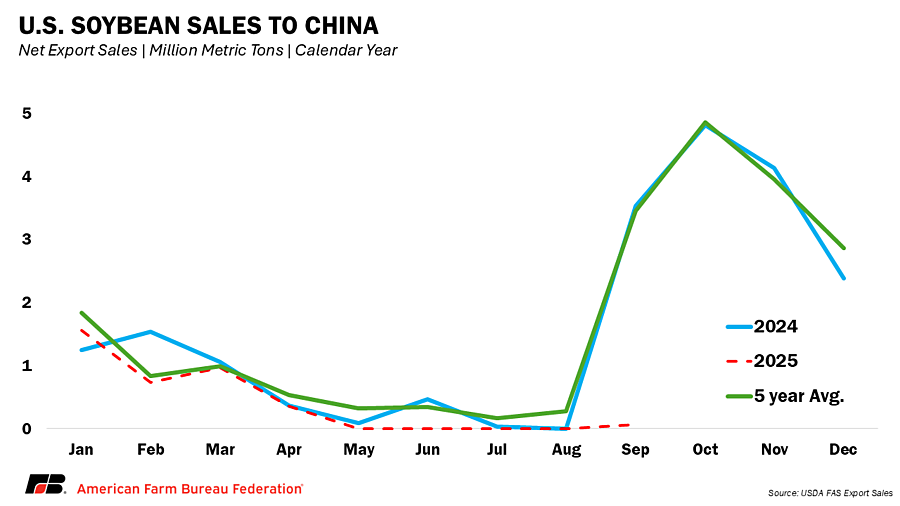

China and Soybeans: A Shrinking Market

Soybean markets have become the clearest signal of stress in U.S. agricultural trade. From January through August 2025, U.S. soybean exports to China totaled just 218 million bushels, down sharply from 985 million bushels in 2024, when China purchased about half of all U.S. soybean exports. During June, July and August, the U.S. shipped virtually no soybeans to China and China has not purchased any new-crop soybeans for the upcoming marketing year.

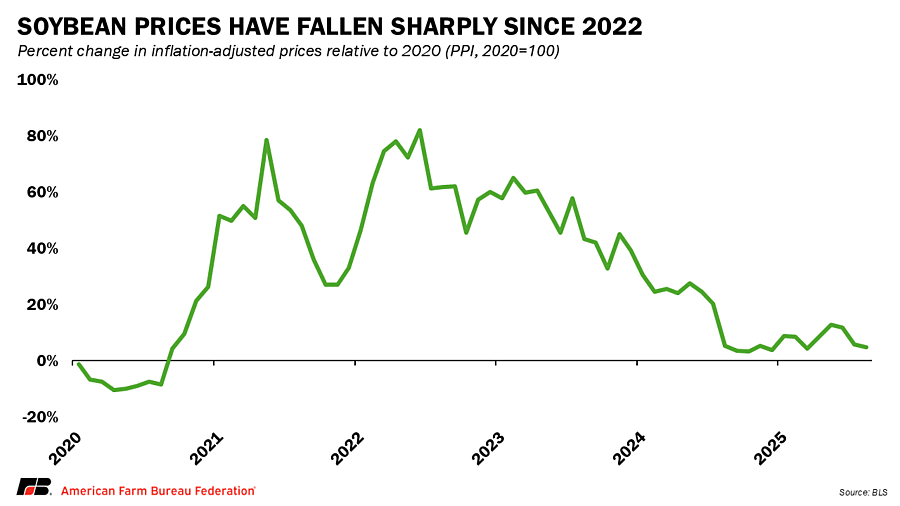

By comparison, Brazil exported about 2.5 billion bushels of soybeans to China over the same period, underscoring how South America has stepped in to dominate the market and displace U.S. farmers. Argentina also sought to boost sales by briefly removing its soybean export tax, only to reinstate it days later after export revenues hit a $7 billion threshold. China’s soybean imports are not shrinking; in fact, they have reached record levels, but the bulk of that demand is now being met by competitors. The ripple effects of trade tensions are showing up in crop markets. Ample global supplies and weaker export demand are weighing heavily on prices for U.S. corn, soybeans, and wheat, cutting into farm revenues despite strong harvests. This is compounded by low water levels in the Mississippi River that is increasing transportation costs.

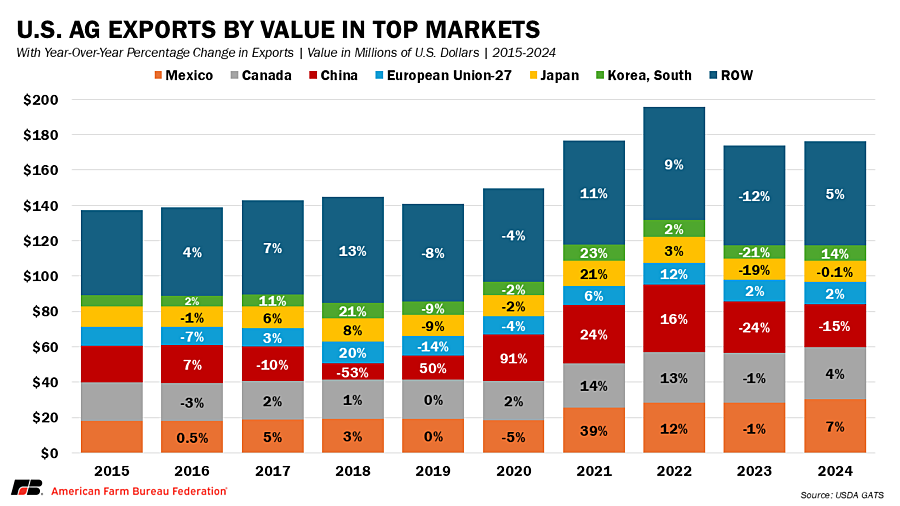

This shift is not limited to soybeans. China has not purchased any U.S. corn, wheat or sorghum this year, and pork and cotton exports continue only at reduced levels. USDA projects that U.S. agricultural exports to China will total $17 billion in 2025, down 30% from 2024 and more than 50% from 2022. In 2026, exports to China are expected to fall to just $9 billion, the lowest level since the 2018 trade war.

The decline reflects more than a single bad year; it is part of a longer trend. In 2012, China purchased more than $25 billion in U.S. farm products, nearly 20% of all agricultural exports. By 2018, sales had fallen to about $9 billion, the lowest level in a decade. While trade partially rebounded in 2020 and 2021 under the Phase 1 agreement with China, the recovery was temporary. Since then, China has steadily diversified its suppliers, turning more to Brazil and Argentina for soybeans, grains and protein. Domestic policy goals in China, including food security and price management, also encourage spreading purchases across multiple countries to avoid dependence on the United States.

The 2025 collapse in soybean trade is the continuation of that broader trajectory. Even when U.S. farmers produce a competitive crop, the absence of consistent Chinese demand leaves a hole in export markets that is difficult to fill. For farmers, the message is clear: relying on one major buyer carries risks and developing new markets is essential to sustaining farm incomes.

The Farm Economy: Why Trade Matters

Trade is not just an abstract policy issue, it is central to the financial health of America’s farmers and ranchers. Roughly 20% of all U.S. agricultural production is exported and those sales are often what make the difference between profit and loss at the farm level. That reliance reflects where demand exists, increasingly in feeding and fueling more and more households outside U.S. borders.

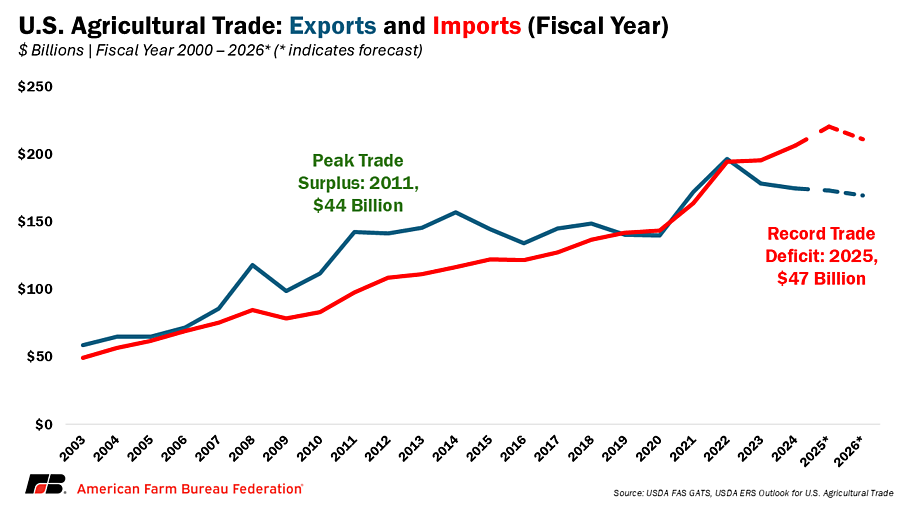

The growing trade deficit underscores this vulnerability. With the U.S. importing more farm goods than it exports, farmers face fewer opportunities to market their crops and livestock abroad. That oversupply puts downward pressure on prices, squeezes margins and adds financial strain in rural communities.

A healthy farm economy depends on reliable markets. Without robust trade, farmers risk oversupply at home, weaker commodity prices and less income to reinvest in their operations.

New Markets Needed

The long-term decline in agricultural trade with China highlights the urgency of developing new markets. While China will likely remain an important customer, the volatility of recent years shows the risks of overdependence on a single buyer.

Expanding access to other markets, through trade promotion programs, bilateral agreements and improved infrastructure, will be critical. Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa all present opportunities for increased U.S. exports of grains, oilseeds and proteins. Programs like the Market Access Program and Foreign Market Development program have historically helped build overseas demand and can play a role in offsetting lost sales to China. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) included the creation of a new Agricultural Trade Promotion and Facilitation Program with $285 million in annual funding starting in 2027 but did not directly raise funding levels for MAP or FMD. Unless Congress separately reauthorizes and funds MAP and FMD in future legislation, the OBBBA-created program would effectively take place of those efforts rather than supplement them.

Alongside efforts abroad, strengthening domestic demand through renewable fuels, biobased products and emerging food markets can help balance the ledger. Farmers have shown resilience before, adapting to shifts in global demand, but they need tools to stay competitive in an increasingly crowded global marketplace.

Conclusion

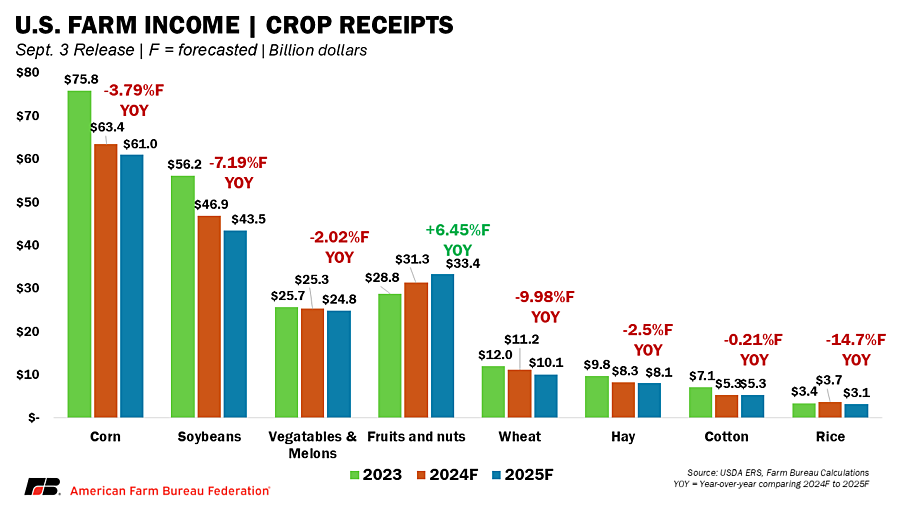

Farmers are facing an extraordinary challenge of declining export opportunities, falling crop prices and rising costs. Without reliable access to key markets, U.S. farm products risk piling up at home, putting downward pressure on prices and tightening margins. USDA’s latest forecast underscores that challenge: cash receipts from crop sales are projected to fall 2.5% from $242.7 billion in 2024 to $236.6 billion in 2025, the lowest level since 2007. The reduction reflects both lower prices and reduced sales volume. For many farmers, weaker demand abroad is compounding financial strain at home, turning strong harvests into tighter margins.

The broader context shows this is not just a short-term disruption but part of a longer trend of reduced Chinese purchases. While trade with China may rebound in certain years, the larger picture points toward market diversification as the best path forward. Farmers will need access to new markets to sustain incomes and manage risk in a more volatile global trade environment.

Agriculture’s role as a cornerstone of the U.S. economy depends on strong trade flows. Policy decisions in the months ahead on tariffs, trade agreements and export promotion will play a major role in shaping the outlook for the farm economy in 2026 and beyond. For U.S. farmers, the stakes are high and the need for dependable trade partners has never been more dire.