U.S. Heading to Record Ag Trade Deficit

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

Trade policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., will impact farmers and ranchers in the countryside. This Market Intel is part of a series exploring agricultural trade, including the potential impacts of trade policy changes.

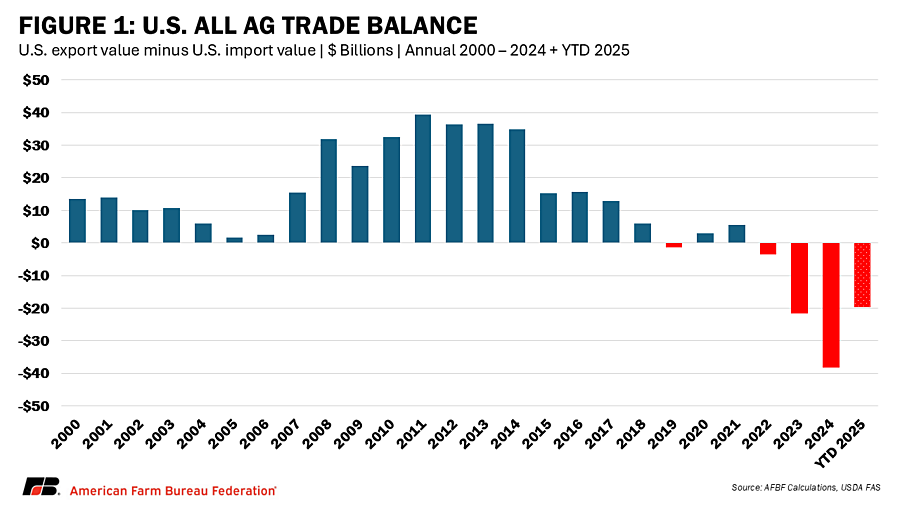

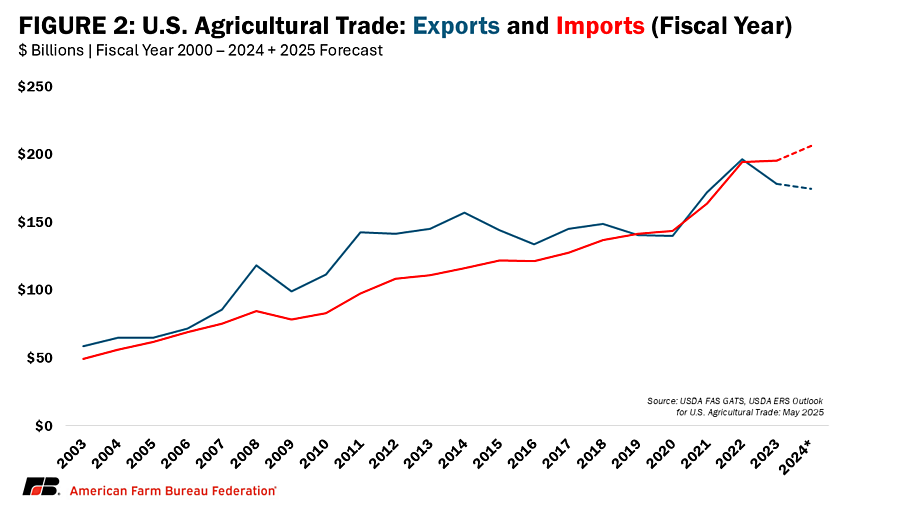

The U.S. agricultural trade deficit is widening in 2025, driven by shifting global trade dynamics and rising import demand. USDA’s Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade: May 2025 report provides projections for exports and imports, offering insight into current trade trends. From January through April, the United States imported $78.2 billion in agricultural products while exporting just $58.5 billion. This $19.7 billion deficit is the largest ever recorded for the first four months of a year and signals that the 2025 deficit could surpass previous records.

After decades of consistent trade surpluses, U.S. agriculture has been in an agricultural trade deficit since 2022. In fiscal year (FY) 2023, the trade gap reached $16.7 billion and nearly doubles in FY 2024 to $31.8 billion. USDA now forecasts the FY 2025 deficit will rise to approximately $49.5 billion, which would mark the largest agricultural trade imbalance on record.

Understanding the Trade Mix

From changing consumer demand and strength of currency to new market opportunities such as the U.S.–U.K. trade agreement, understanding what’s driving the deficit is key to supporting U.S. farmers, ensuring a strong agricultural economy and, as discussed in a previous Market Intel – Agricultural Imports 101, protecting U.S. food security.

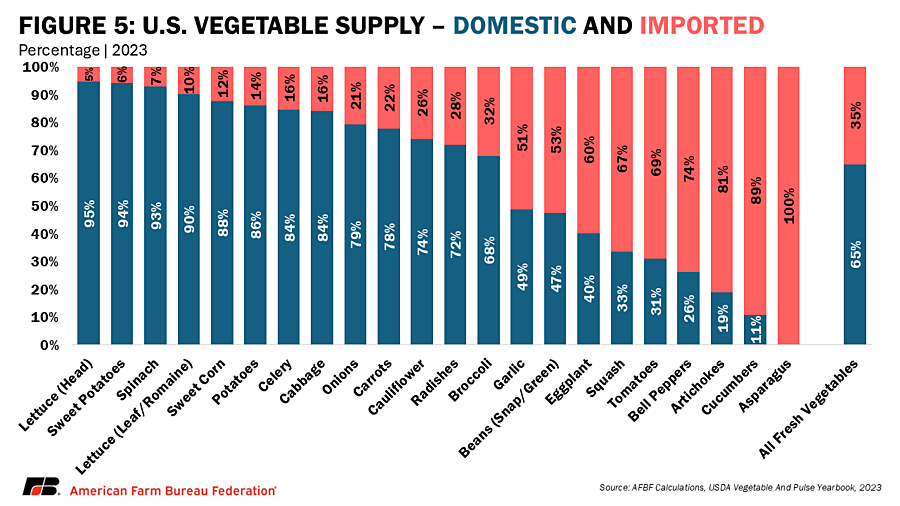

The United States imports products to ensure year-round access to fresh produce and goods not widely grown domestically. Coffee, for example, is almost entirely imported, since production is limited in Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

While some seasonal producers face competition from imports, many imported goods do not directly compete with U.S. crops or are made using U.S.-grown ingredients. In other cases, imports complement domestic production. Oranges are a good example. Most oranges consumed in the winter and spring are grown in the United States, but during the off-season, imports help meet consumer demand and keep shelves stocked. To learn more about our agricultural trade mix see Exports 101 and Imports 101.

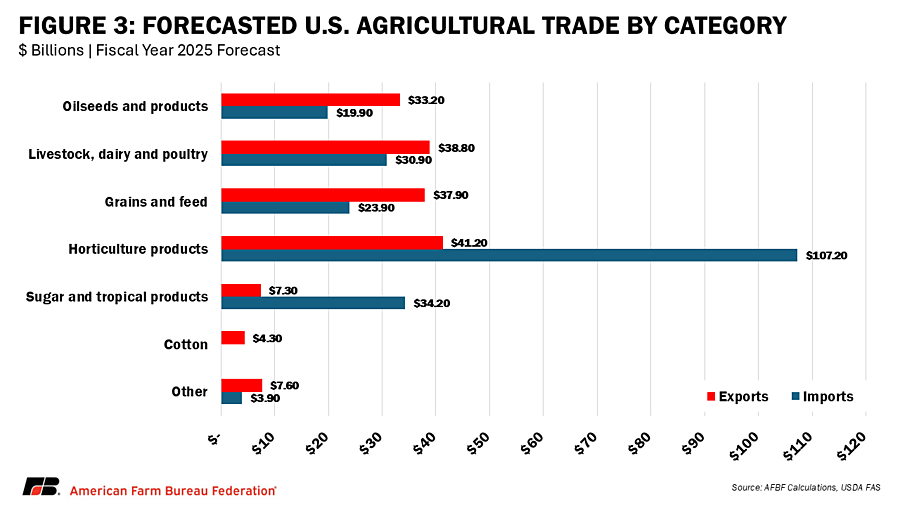

In FY 2025, USDA projects that horticultural products, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, wine and other alcohols, will account for approximately 49% of total agricultural imports by value. These products reflect consumer preferences for variety and year-round availability and highlight the role of trade in maintaining a stable food supply. Strong U.S. demand for high-value, consumer-ready products, many of which are not widely produced domestically, has driven up import values, while a large share of U.S. exports remain lower-value bulk commodities, contributing to the growing trade imbalance.

Why U.S. Agricultural Exports Are Slowing

While imports continue to rise, U.S. agricultural export value, after reaching record highs in 2022, has since declined. A strong U.S. dollar and high labor costs have made American goods more expensive for foreign buyers, weakening global competitiveness. At the same time, trade barriers, retaliatory tariffs and ongoing disputes have limited access to important markets such as China and the European Union. Some foreign buyers are turning to lower-cost suppliers like Brazil and Argentina. These challenges point to the need for the United States to pursue new trade agreements and strengthen existing ones to expand export opportunities.

U.S.–UK Trade Deal

In May 2025, the United States and the United Kingdom announced a new trade agreement focused on expanding agricultural market access. The UK represents a high-value export destination for U.S. agriculture, with total exports reaching approximately $2.18 billion in 2024. Leading U.S. exports to the UK included horticultural products such as wine and tree nuts, along with ethanol fuel.

The deal removes key U.K. tariffs, including the 20% duty on U.S. beef and tariffs on American ethanol. These changes are expected to create growing export opportunities, especially for beef and corn producers. U.S. products must comply with UK standards, which still prohibit hormone-treated beef and chlorine-washed poultry.

The agreement also gives British exporters a limited quota to send beef to the United States tariff-free. Although not a full free trade agreement, the deal is viewed as a meaningful first step and sets the stage for broader negotiations on issues.

Conclusion

USDA’s May 2025 forecast projects the largest agricultural trade deficit in U.S. history. This growing gap highlights the need to resolve current trade disputes, expand export markets and protect fair trading conditions for American farmers and ranchers. Agreements like the U.S.–U.K. deal can help diversify export destinations and reduce exposure to market disruptions. As global competition intensifies, strong trade policy will play a central role in farm profitability. The latest USDA report makes it clear that closing the trade gap will require continued efforts to build reliable, science-based access to global markets for the long term.