Economics of U.S. Beef and Cattle Market

Bernt Nelson

Economist

U.S. cattle farmers have faced significant challenges in recent years, from COVID-19-related supply chain disruptions, low cattle prices and persistent drought conditions to growing threats of invasive pests and diseases, a decades-low supply of beef cows and historic inflation in production costs.

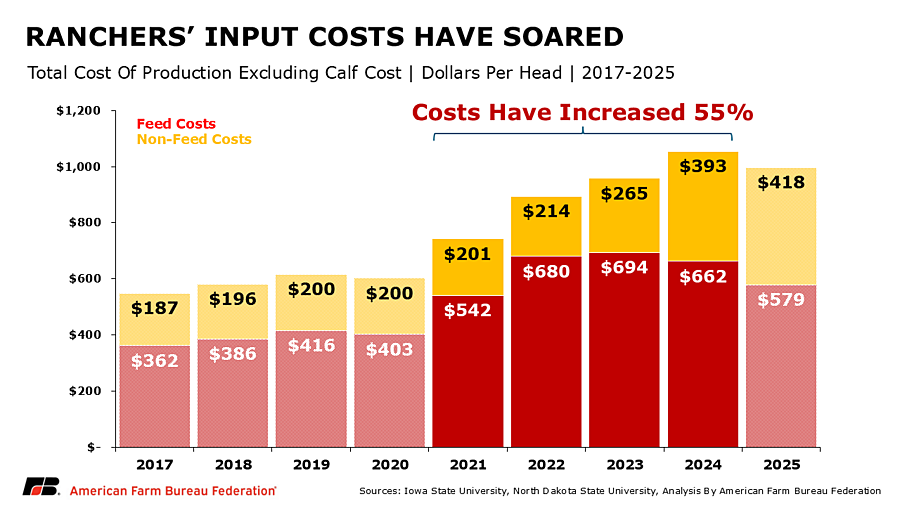

For the first time in a long time, cattle ranchers, backgrounders, stockers and cow-calf producers are experiencing dependable economic returns, allowing them to rebuild working capital and consider restocking America’s beef herd. However, record-high production costs make efforts to grow the cattle herd more difficult. Those efforts are also sensitive to interventions in the market designed to lower consumer beef prices, which have the unintended consequence of lowering the prices paid to U.S. cattle farmers.

Supplies

Right now, positive economic returns could provide farmers and ranchers incentives to rebuild the cattle herd, but if prices fall, and returns disappear, the cattle herd could continue contraction.

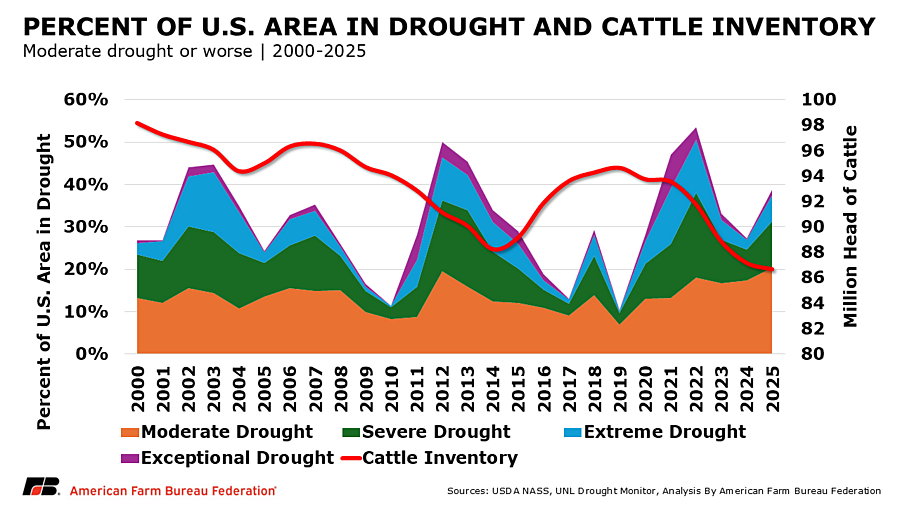

The roughly 10-year expansion and contraction in the U.S. cattle herd in response to perceived profitability is called the cattle cycle. The U.S. is currently in year 12 of the cattle cycle and year seven of cattle herd contraction. At 86.7 million head, U.S. cattle supplies were at their lowest in 74 years on Jan. 1, 2025, due to unprofitable prices, persistent drought, and record costs to raise and feed cattle.

Drought and Pasture Conditions

Pastures are where the nation’s breeding cattle are raised. Good pasture conditions lower the costs of raising a healthy breeding herd. Drought, especially on-going drought, damages pasture long-term and drives up costs for ranchers, who have to ship in hay from other parts of the country. Deteriorating pasture conditions were a big factor in farmers’ decisions to place female cattle on feed from 2021-2023, rather than keeping them to produce calves. Higher numbers of female cattle going to market led to the drop in the cattle inventory and fewer cattle available for beef production.

Rebuilding the cattle herd takes a long time. If a farmer decides today to keep a heifer instead of placing it on feed for market, it will take 30 months before that heifer produces a calf that creates meaningful growth in the cattle herd, putting us in 2028 before cattle supplies reflect that decision. However, if cattle prices fall and farmers can’t make a profit, they may market females, leading to fewer cattle supplies available for beef in the long run. For many ranchers, the past several years have included painful decisions. When ponds and springs dried up, some hauled water by the truckload just to keep animals alive a few more weeks. Others paid record prices to bring in hay from hundreds or even thousands of miles away, often spending more on freight than on the feed itself. Selling off breeding cattle wasn’t just an economic decision, it was an emotional one, representing years or even generations of herd development lost in a single season. Drought has forced families to part with genetics they had spent decades refining, knowing it could take years to recover what was sold in a matter of weeks.

Demand

U.S. beef demand has remained strong even as beef prices hit record highs. USDA’s September WASDE report projects that U.S. beef consumption is strong in 2025 at 28.6 billion pounds but is expected to fall about 2% to 28 billion pounds in 2026. With the supply side largely fixed, U.S. demand for beef is the lynchpin helping our nation’s cattle farmers and ranchers remain economically viable. Strong demand has driven retail prices higher. In the case of beef, this means higher prices paid for wholesale, which means higher prices for fed cattle, feeder cattle, and even new calves. If demand for U.S. beef weakens, whether due to increased beef imports or changing consumer preferences, cattle prices will likely decline. This would create a major obstacle to any meaningful expansion of the U.S. cattle herd.

Prices

This is a demand-driven market. Demand for American beef paired with low cattle supplies drive beef prices up. In recent years, the cattle industry has been one of the few sectors in agriculture operating in the black. Record input and supply costs mean cattle farmers and ranchers are walking a thin line between making and losing money. After years of drought and liquidation, many simply don’t have the volume of animals needed to generate dependable income, even when prices are strong. That limited inventory makes it harder to take advantage of high prices or reinvest in expansion. If prices drop even a little, it could wipe out what little profitability exists. If that happens, farmers and ranchers don’t have a reason to grow their herds but instead have a reason to sell, which could lead to more contraction in the U.S. cattle herd and push beef prices higher.

All Americans benefit from a strong domestic food supply that includes beef from the nation’s cattle herd. The current price environment for America’s cattle producers is providing the economic signals needed to ultimately grow the U.S. herd. However, it's important to remember that when farmers start to keep more animals to grow more beef, that means there will be fewer available to put in the supply chain for food. This means less beef available in the short run until the breeding animals can produce a calf, i.e., 30 months.

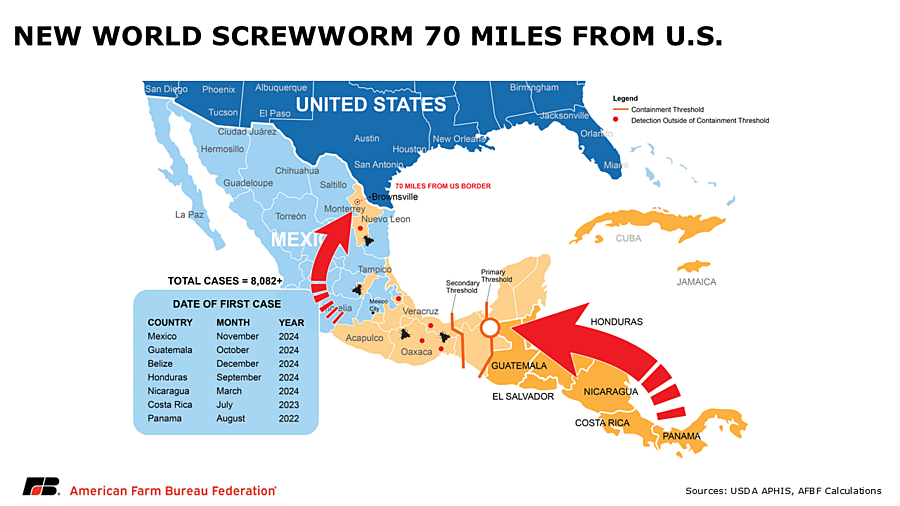

New World Screwworm

To protect the U.S. from a new threat posed by an old foe, the New World screwworm (NWS), the U.S.-Mexico border was closed on July 9, 2025, and remains closed to cattle, bison and horses from Mexico. This pest was eradicated from the U.S. in 1966 and eliminated as far south as Panama by 2000. Since 2022, NWS has moved north through Central America and has been detected just 70 miles south of the border between the U.S. and Mexico. The U.S. typically imports about 1.3 million head of cattle from Mexico. NWS is a serious but treatable animal health and economic threat that could cost the U.S. billions and adds further uncertainty to cattle growers’ future returns.

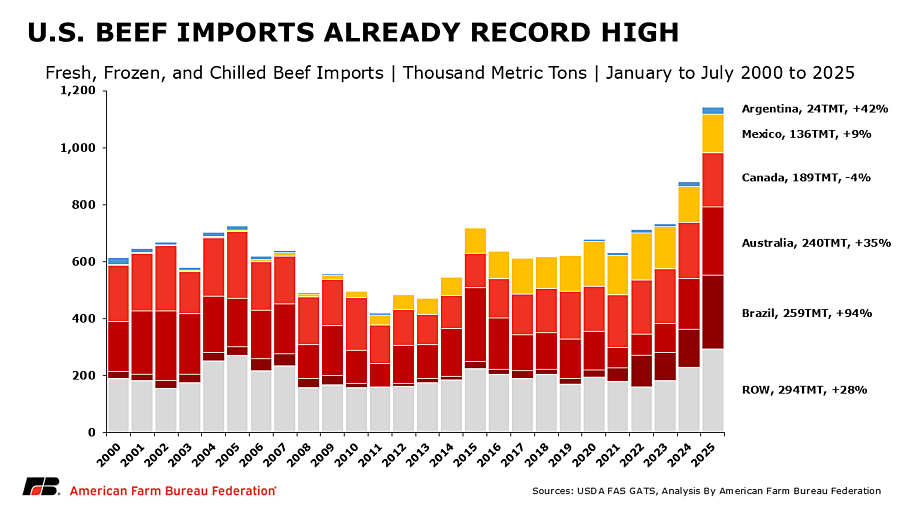

Imports

Imports are mostly used to help balance the domestic supply of lean and fat beef trimmings used for ground beef. While lower cattle supplies affect that balance, so do heavier fed cattle carcass weights, which give us more fat trimmings, leading to a need to import lean trimmings. Over the past few years, beef imports have risen to record levels to help supply processors with enough lean trimmings to blend with U.S. fat trimmings to turn into ground beef. Year-to-date beef imports are approaching 1.2 million metric tons or about 10% of U.S. consumption, with imports from Brazil up 94% year-over-year at nearly 260,000 metric tons.

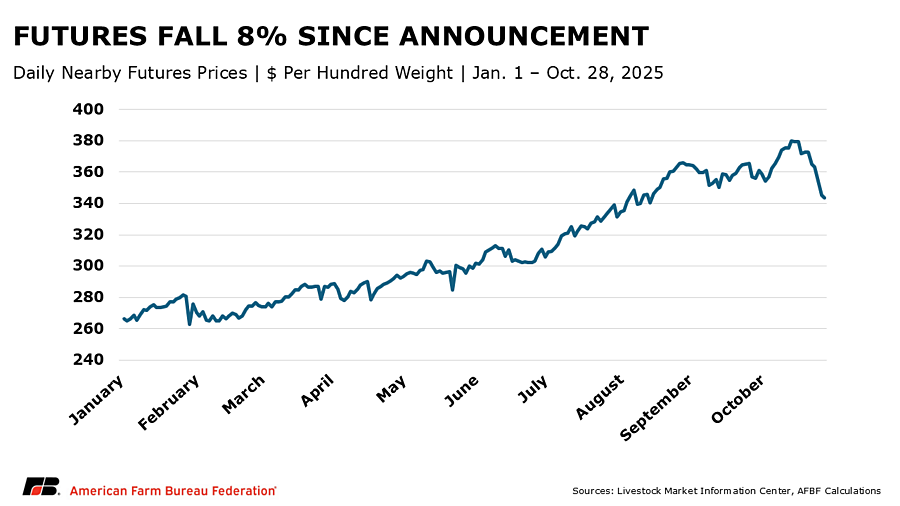

On Oct. 23, the administration announced it would increase the tariff rate quota for beef from Argentina in an attempt to lower consumer beef prices. Since 2020, about 2% of U.S. beef and veal imports have come from Argentina. Under the current tariff rate quota, Argentina can sell 20,000 metric tons of beef per year to the U.S. at a lower tariff. After the quota is met, the tariff increases. So far in 2025, about 30,000 metric tons of beef have been imported from Argentina, about 10,000 metric tons above the tariff rate quota and over 40% higher than last year. An increase to 80,000 metric tons would account for about 3.5% of the total U.S. beef import volume to date and about 0.6% of USDA’s forecasted U.S. beef consumption for 2025. This amount will not have a measurable impact on prices consumers pay for beef, but the announcement has already caused future prices for feeder cattle to fall by 7%.

Summary

Several years of drought, low cattle prices, and record-setting input and supply costs have led to a shrinking cattle herd, which, paired with strong consumer demand for beef, has pushed prices for beef and cattle to record levels.

Cattle farmers and ranchers are operating in the black for the first time in a long time, but margins are vulnerable and could be wiped out should prices begin to fall. Market intervention efforts, including increased imports, would add another barrier to growing the cattle herd and potentially incentivize more contraction in the cattle inventory. This could drive beef prices even higher and increase U.S. reliance on imported beef to meet domestic demand.