Declining Farm Economy Continues to Pressure Profitability

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

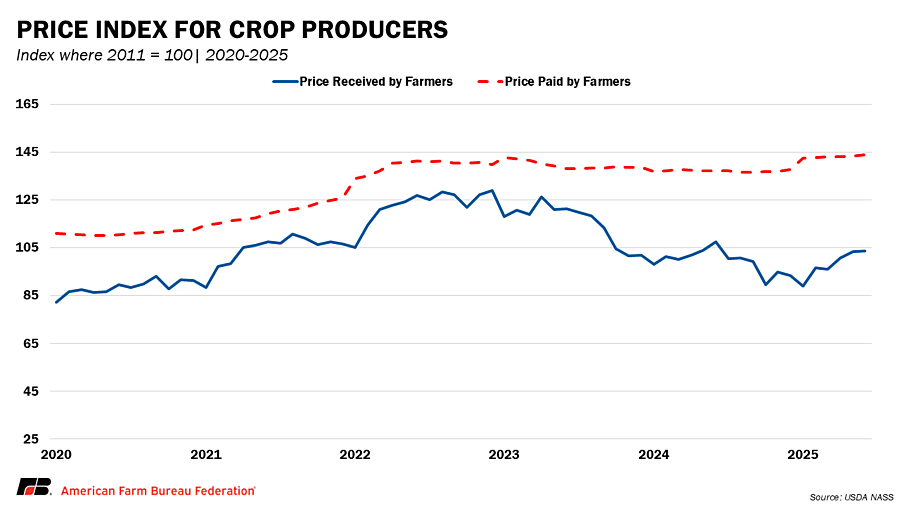

For most of the country, farmers face a difficult farm economy – as crop prices continue to decline and production expenses remain high. Strong yields provide little relief and imbalance in the market has driven profit margins to the point where breaking even is unachievable. Commodity prices have plummeted from their 2022 highs, creating a persistent imbalance in the farm economy that places real strain on the financial health of row crop farmers across the country.

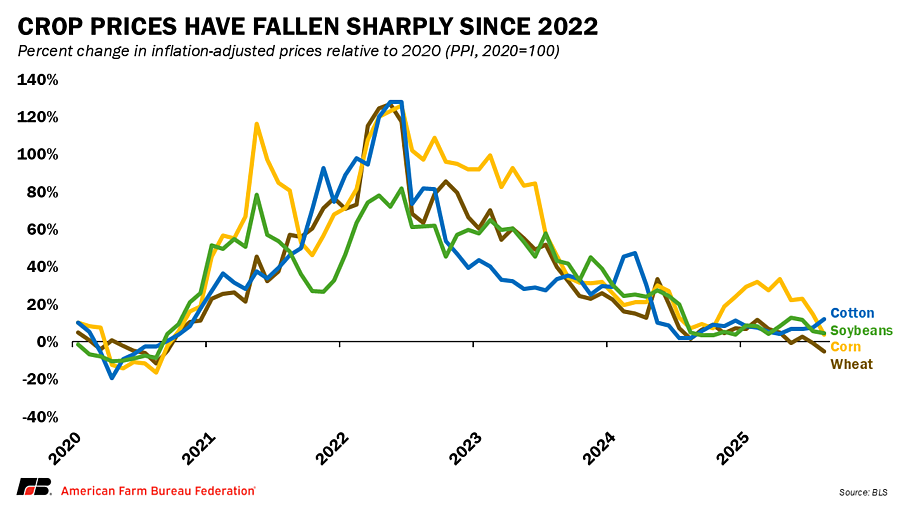

Commodity Prices Declining

After the high prices of 2021 and 2022 driven by strong global demand, persistent drought and supply chain disruptions driven geopolitical tensions, markets have cooled. Corn that once topped $7 per bushel is closer to $4 today, down 54%. Soybeans have slipped below $10 per bushel after running at $15 just three years ago (decrease of 58%). Wheat prices have decreased 51% despite weather worries and cotton has come down 42% from COVID-19 pandemic highs.

One of the biggest drivers has been export demand. China, once the largest customer for U.S. soybeans, has shifted heavily toward South America, especially Brazil, where farmers harvested record crops at competitive prices.

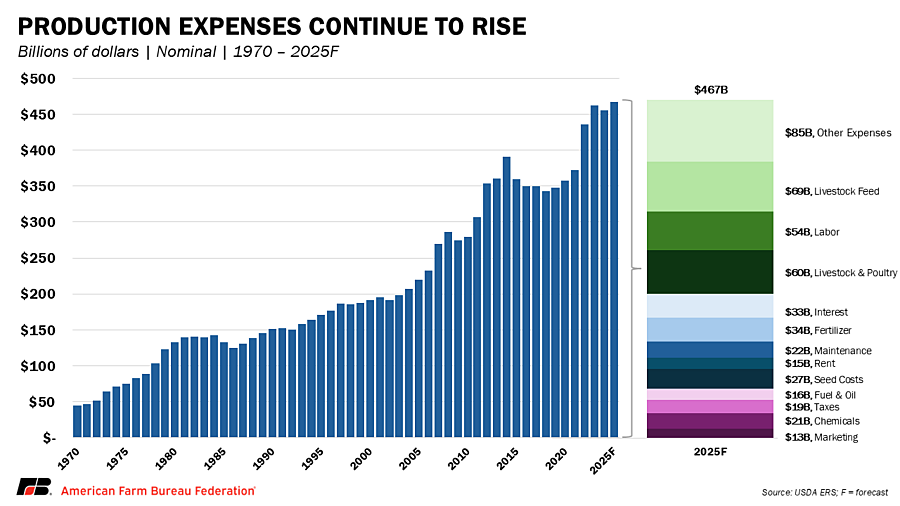

Production Expenses Squeezing Farmers

As crop revenues continue to decline, expenses remain stubbornly high, leaving farmers with very few options beyond drawing down equity, tapping reserves or taking on more costly debt. Production expenses in 2025 are projected at record levels of $467 billion, nearly $12 billion higher than 2024 (up 2.6%), $50 billion above the previous five-year average (12%) and $85 billion above the previous ten-year average (21%). Each major cost category tells the same story: inputs remain elevated, eroding profitability and making it harder for farmers to reinvest in their operations or build financial reserves.

Seed

Seed is a critical part of farm production budgets, with U.S. farmers expected to spend $27.2 billion in 2025, about 6% of total expenses. Modern seed technology offers advantages such as pest resistance and higher yield potential, but those traits come at a premium. Although USDA data show seed costs have remained relatively steady in recent years, they are not an expense farmers can easily reduce. Cutting back on seed quality risks lower yields, making seed a necessary and consistent cost for most operations.

Crop Protection

Herbicide, fungicide and insecticide programs are also becoming more complex and expensive. Many active ingredients must be imported, leaving U.S. farmers exposed to global supply disruptions. Crop protection expenses in 2025 are projected at $20.6 billion, or 4% of total costs, underscoring how resistance and global volatility feed directly into farm budgets. Crop protection is a necessary input that farms rely on to grow healthy crops without damage from pests and disease. U.S. farmers remain global leaders in efficient and responsible use of crop protection products, growing more per acre with fewer inputs than many of their competitors.

Energy and Fuel

Energy is another essential expense that has proven difficult to control. Diesel fuel powers planting and harvest, while propane is critical for drying grain. Global oil price swings ripple through to the farm gate, and higher freight costs further increase the price of both inputs and marketing crops. Fuel and oil are projected at $15.8 billion in 2025, about 3% of all costs, keeping energy a meaningful line item even when oil markets stabilize.

Machinery and Repairs

Farmers are also facing higher costs to keep machinery running. New equipment is increasingly expensive with deliveries often delayed, leading many growers to extend the life of tractors and combines. With downturns in the ag economy, many farmers are choosing to put off the large capital expense of new equipment until their margins improve. The tradeoff is higher repair and maintenance bills. Inflation in parts and service has made routine upkeep more costly, pushing total maintenance expenses to $22.2 billion, about 5% of costs in 2025. For farm families already managing thin margins, those costs can no longer be considered minor.

Fertilizer

Fertilizer is one of the most significant drivers of cost. Although prices have retreated from the 2022 peak, they remain well above pre-2021 levels. Global supply chains, natural gas (a component fertilizer manufacturing) markets and geopolitical instability all feed into unpredictable price swings, creating uncertainty for farmers. Because fertilizer is traded in a global market, U.S. farmers compete with growers overseas who need fertilizer for growing crops like coffee that are not widely grown domestically. Strong prices for those commodities sustain global fertilizer demand, keeping input costs elevated in the U.S. even as commodity prices weaken. Fertilizer is forecast at $33.5 billion in 2025, about 7% of all expenses, representing one of the largest single costs for row crop operations.

Land Costs

Cash rents and farmland values are at record highs, reflecting the pressure of limited supply and continued demand for productive land. Rent alone is projected at $15.2 billion in 2025, about 3% of total expenses, making it one of the largest fixed costs for many row cropgrowers. For beginning farmers, high land values create a barrier to entry, while tenants face tight margins as rents absorb more of their crop revenue.

Interest

Higher interest rates are hitting farmers on two fronts, raising the cost of short-term operating loans needed to cover seasonal input purchases, while also raising the cost of long-term investments in land or equipment. Interest payments are expected to reach $33.1 billion in 2025, roughly 7% of all costs, directly reducing farm profitability. For highly leveraged operations, interest is now one of the biggest threats to financial stability.

Labor

Although row crops are heavily mechanized, labor remains essential during planting and harvest. Skilled workers are increasingly difficult to find and wages continue to rise in tight rural labor markets. Labor expenses are projected at $53.7 billion, or 11% of total costs in 2025, making labor the second-largest cost category after livestock feed. For larger operations, labor shortages and higher costs are now a central challenge to maintaining efficiency.

Profitability Outlook for the Farm Economy

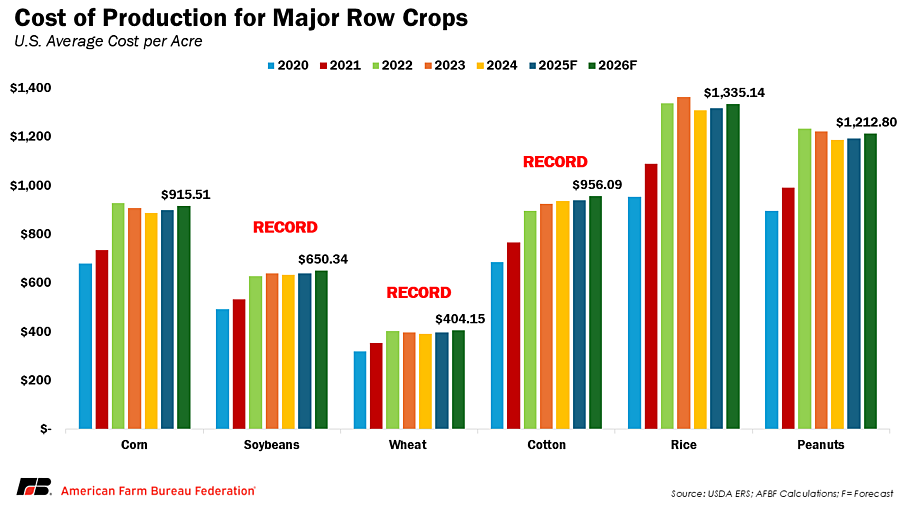

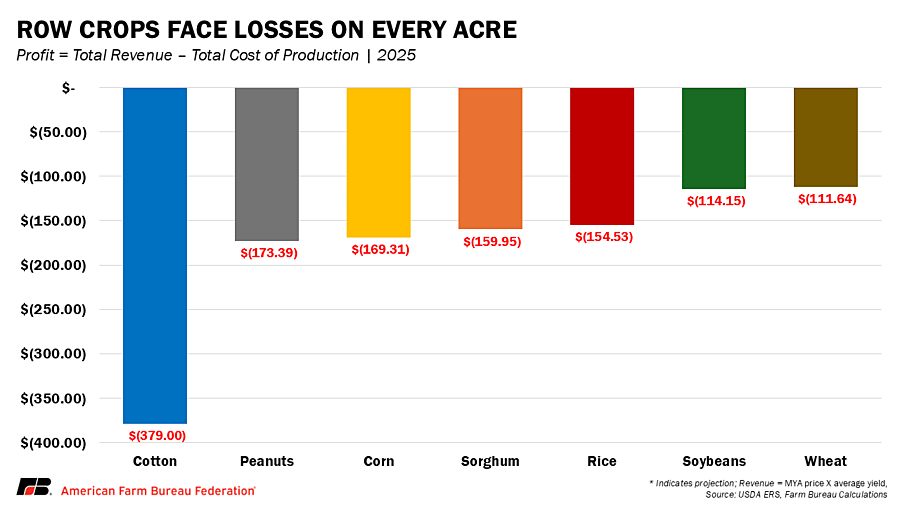

With crop prices trending down and expenses holding firm, row crop farmers are facing shrinking, and often negative, profit margins. Strong yields are not enough to guarantee profitability when costs absorb so much of the limited revenue.

As such, profitability per acre is negative across most major crops:

- Cotton: –$379.00 per acre

- Peanuts: –$173.39 per acre

- Corn: –$169.31 per acre

- Sorghum: –$159.95 per acre

- Rice: –$154.53 per acre

- Soybeans: –$114.15 per acre

- Wheat: –$111.64 per acre

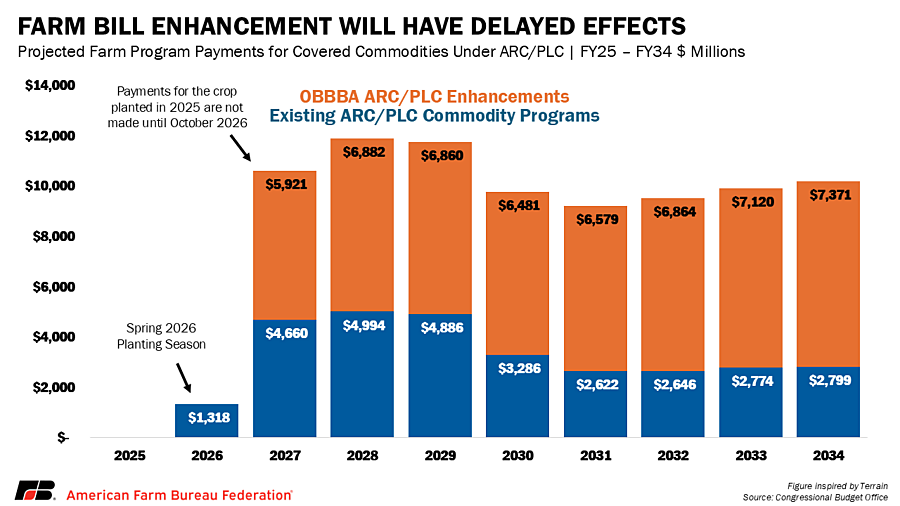

These numbers underscore how the cost-price squeeze is leaving little room for farmers to cover debt obligations, reinvest in their operations or build reserves for future years. Programs like Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) provide stability when markets fall, and crop insurance helps farmers manage unpredictable weather and yield losses. However, they were not designed to weather persistent cost inflation. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) makes meaningful progress by raising reference prices and expanding crop insurance options, steps that will provide stronger protection for row crop farmers once they take effect. These changes reflect the importance Congress placed on reinvesting in the safety net, and farmers are grateful for that commitment. The challenge is timing, as most of the improvements will not be in place until October 2026, leaving growers to navigate today’s tight margins without these tools. Ensuring a smooth transition until the new provisions begin will be key for helping farm families stay afloat and manage the years ahead.

About the Farm Economy

Row crop farmers are stuck in a cost-price squeeze that threatens profitability even in years of good harvests. Prices for corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton have all fallen from recent highs, while costs for seed, chemicals, energy, equipment, fertilizer, land, interest and labor remain stubbornly high. Many specialty crop growers also face similar headwinds, though limited public data make it harder to reveal per-acre profitability as easily.

Past Market Intels highlight how these challenges connect: fertilizer, farm income, trade, and farm structure. Global competition, policy uncertainty and rising expenses keep pressure on the farm economy.

Additionally, farm financial stress is already showing up in the data through higher farm losses and more bankruptcy filings. While Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies remain below the long-term average, they have been creeping up as lower crop prices and elevated expenses eat into working capital. In 2024, over 200 farms filed for bankruptcies. However, many farms are not eligible to file for Chapter 12 bankruptcies. In fact, the U.S. has completely lost more than 140,000 farms from 2017 to 2022, and an additional 20,000 in the last two years.

The outlook depends on both market recovery and policy implementation. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act makes important progress by raising reference prices and expanding crop insurance options, but most provisions do not take effect until late 2026. Until then, both row and specialty crop farmers must continue operating in an environment where global input costs remain high and crop returns are negative. Managing this gap will be critical to sustaining farm families and maintaining the resilience of U.S. agriculture. Until then, row crop farmers must continue operating in an environment where global input costs remain high and crop returns are negative. Managing this gap will be critical to sustaining farm families and maintaining the resilience of U.S. agriculture. Managing this gap will be critical to sustaining farm families and maintaining the resilience of U.S. agriculture.