Inflation and Interest Continue Driving up Farmers’ Costs

TOPICS

Inflation

Bernt Nelson

Economist

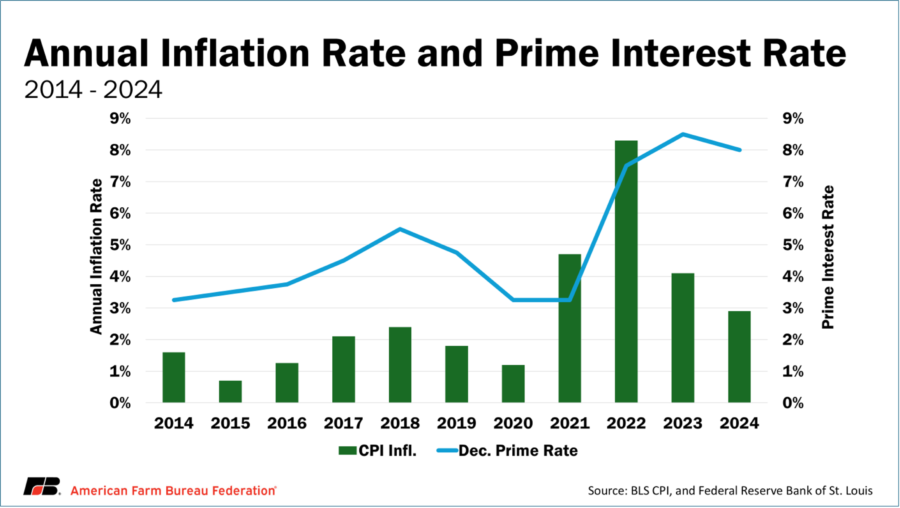

In 2020, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) responded to an acute recession by cutting interest rates and launching large-scale asset purchases to support credit and stimulate demand. Then, inflation in 2021 and 2022 reached levels not seen since the 1980s. To combat this, the Fed began raising interest rates in March 2022 to slow demand and reel in the money supply. While inflation has since softened, so too have prices for many of the crops grown by U.S. farmers. Meanwhile, interest rates remain above typical 21st-century levels as the Fed works to address inflation. This Market Intel provides an update on inflation and the impacts on farmers.

Inflation

Inflation is the rate at which the prices for goods and services rise. As inflation increases, it pulls down the purchasing power of money, meaning each dollar does not go as far. According to the Fed, a healthy level of inflation to reflect general economic growth is about 2%.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) measures inflation using their Consumer Price Index (CPI) The most recent report was released on Aug. 12 and found that the July CPI was 2.7% higher than a year ago, on par with June projections and below general expectations. Core inflation for goods and services minus food and energy is typically more volatile and hit a five-month high of 3.1%, which is slightly higher than expected by analysts.

The Fed’s primary tool to help steer the economy is the effective federal funds rate (EFFR). This is the rate banks charge to lend their excess deposits to one another to meet minimum reserve requirements. Changes in the federal funds rate directly influence the interest rates for mortgages, auto loans, credit cards and business financing. When rates go down, banks can lend at lower costs, making it cheaper for consumers to borrow and spend and for businesses to invest, which increases demand. The opposite happens when interest rates go up.

Farm Impacts

A lower inflation rate does not mean goods and services are getting cheaper; rather, it means prices are increasing at a slower pace. For farmers and ranchers, the cost of growing crops and caring for livestock has gone up exponentially in recent years. At the same time, farmers remain at the mercy of slipping commodity prices, volatile weather conditions and an uncertain trade environment.

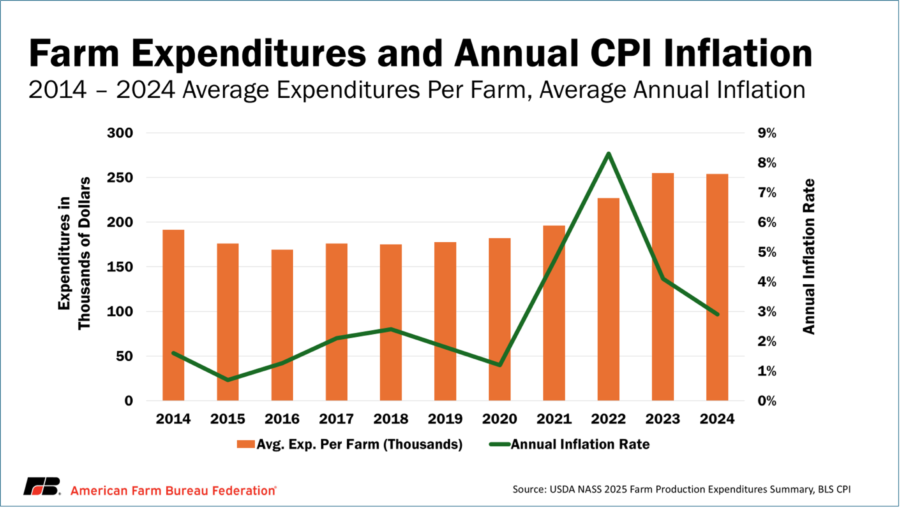

USDA’s 2025 Farm Production Expenditures Annual Summary contains the 2024 estimates of farm production expenditures like feed, farm services, rent, agricultural chemicals, fertilizer, lime and soil conditioners, interest, taxes (real estate and property), labor, fuel, farm supplies and repairs, farm improvements and construction, tractors and self-propelled farm machinery, other farm machinery, seeds and plants, trucks and autos. According to the report, total U.S. farm expenditures in 2024 are estimated at $477.6 billion, down about $4.3 billion (0.9%) from the record-setting $481.9 billion in 2023. The average expenditure per farm was $254,043 in 2024, down slightly from the record-high $255,047 in 2023. Lower inflation is partially behind the drop in expenditures because it slowed down the rise in supply costs. More importantly, falling commodity prices have reduced the price of feed for livestock.

As previously discussed in a recent Market Intel, farm expenses have been consistently higher than the prices received for crops grown for the last five years, according to USDA’s price indexes for crop producers. The gap between prices received and prices paid has grown wider due to falling prices, particularly since 2023, but this long-term trend indicates that even higher prices have not been enough to combat the rise of input and supply costs.

Corn and soybeans account for about 52% of all planted crop acres in the U.S., making them a significant contributor to farm revenue across the country. In the August World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report, USDA forecasted the average farm price for corn to be $3.90 per bushel in 2025/26, 35% below the marketing year average (MYA) price of $6 per bushel in 2022/23. USDA forecast the average farm price for soybeans at $10.25 per bushel in 2025/26, 23% below the 2022/23 MYA price of $13.30 per bushel. These prices, well below breakeven for the third year in a row, have driven farms to increasingly rely on credit to continue operating.

Credit

Following the Fed’s adjustments since 2022, the EFFR is currently 4.33%, up from near-zero levels in 2020. EFFR is calculated daily and it’s important to note that EFFR is different from the federal funds target rate.

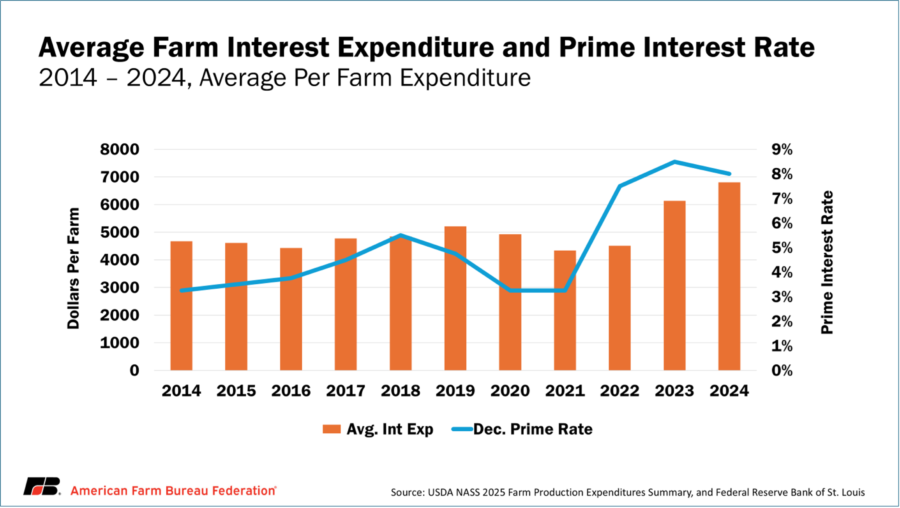

The increases in the EFFR have a substantial influence on the prime interest rate in the U.S. The prime rate is the minimum interest that banks charge their most credit-worthy customers for borrowing money. The current prime rate is 7.5% and was set Dec. 19, 2024. The bottom line is, when the Fed increased rates, they dramatically increased the cost of borrowing money across the economy. This has happened at a time when farmers and ranchers rely more heavily on credit due to the growing gap between commodity prices and input costs.

The rise in interest rates has driven up the cost of borrowing money. According to USDA estimates, the average farm spent about $6,809, 2.7% of their total expenses, on interest in 2024. The total average interest expenditure per farm has increased by 46%, or $2,173, from $4,672 to $6,809. Meanwhile, overall expenditures have risen 33%, from $191,500 in 2014 to $254,043. The sharp rise in total farm expenditures means the steep increase in interest costs still represents only a modest share of overall spending, but credit is more critical in low price years, making it a crucial expense that continues to increase.

While the interest increase of $2,173 per farm might seem smaller than expected, it’s important to remember that not all farms carry recurring debt. This stark gap is also partly due to USDA’s broad definition of a farm, which includes any operation with more than $1,000 in ag product sales — a threshold that encompasses many very small-scale or lifestyle farms not intended to provide primary income.

A financing tool commonly used by farmers and ranchers is an operating loan. An operating loan is a type of short-term loan to cover the day-to-day costs of running the farm or ranch. These loans are typically paid off and renewed every year. According to USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS), about 22% of farms carried debt of some kind in 2022 when the Fed began raising interest rates. Interest rates for operating loans nearly doubled between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2023. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, the median operating loan interest rate was slightly below 8% for the second consecutive quarter of 2025.

Despite increasing costs of credit, farmers continue to borrow more. The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago notes about 40% of ag bankers expected higher operating, feeder cattle and FSA guaranteed loan volumes this year than last. Higher interest rates combined with higher loan volumes have only elevated the losses being endured by many farms for the third consecutive year as they struggle to cover daily growing expenses.

The U.S. has lost 20,000 farms since the last Census of Agriculture. The census indicated 142,000 farms were lost between 2017 and 2022, that’s more than 77 farms per day. Worsening credit conditions are likely to add to farm losses and bankruptcies in the days ahead.

Conclusion

Without question, inflation impacts every family in America. Small businesses like farms and ranches are especially impacted by increased cost of their inputs (like seed and fertilizer) coupled with higher interest rates on the yearly operating loans necessary to acquire those critical inputs. And layered on top of inflation and the cost of interest, are plummeting crop prices and significant declines in agricultural exports. Farm country is hoping for a break in any one of the challenges they face. Will the September meeting of the Fed provide farmers and ranchers with positive news?