Farm Bill Title I Commodity Programs – ARC, PLC and Marketing Assistance Loans

photo credit: AFBF photo/Morgan Walker

Shelby Myers

Former AFBF Economist

For nearly 100 years, the history of the farm bill largely tracks the history of food production in the United States as the legislation evolves to meet the needs of its modern-day constituents – farmers and consumers. Agriculture’s role in providing food security, and in turn national security, to the United States is more important than ever. And now, work on the next farm bill has started during a period of volatility on every front – political, economic and beyond. So why is this food and farm bill so impactful and influential?

Continuing the Market Intel series of articles that dive deeper into farm bill programs, this article covers risk management programs in Title I specific to shallow-loss coverage of commodities.

Recent History of Title I

Title I of the farm bill, known as the commodity title, has provided certainty and predictability to eligible producers by reauthorizing and improving commodity, marketing loan, sugar, dairy and disaster programs. In short, it has provided benefits based on price or revenue targets for commodity growers in the United States. The title mainly refers to programs for “covered commodities,” as they are often referred to, which include corn and feed grains, wheat, rice, soybeans and other oil seeds, peanuts and pulses, as well as cotton seed. Some additional commodities have options for assistance through marketing assistance loans, non-recourse loans, marketing allotments, and others as discussed later in this article.

Some of the most recent historical changes for Title I occurred in the 2014 farm bill, which ended the Direct and Counter-Cyclical Program (DCP), which included two types of payments, a direct payment and a countercyclical payment, and the Average Crop Revenue Election (ACRE) program. DCP, a direct payment program, provided a fixed annual payment to producers on historical base acres and yields regardless of whether the farm experienced a loss. The program provided producers countercyclical payments on historical base acres and yields triggered by movements in prices. ACRE was the alternative to DCP and was a revenue-based program that paid producers when revenues fell below specific benchmark levels.

Two new programs were created in the 2014 farm bill to fill the void of the repealed DCP and ACRE: Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC). Both programs were set up to make payments on historic base acres and were decoupled from production to minimize the programs’ influence on farmers’ decisions about what crops to plant and where.

Additionally, nonrecourse Marketing Assistance Loans were made available to covered commodities, as well as an extended list of commodities that included upland cotton, which was removed from Title I programs in the 2014 farm bill due to a World Trade Organization case settlement with Brazil. Sugar growers have a separate price support program that involves non-recourse loans, marketing allotments and import quotas. Dairy and disaster programs are also in Title I and discussed in Overview of Dairy Programs in the Farm Bill and Revisiting Disaster Programs in the Farm Bill.

Title I Commodity Programs

The 2018 farm bill reauthorized and strengthened the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) options for crop years 2019-2023. These programs were created in the 2014 farm bill to provide shallow-loss risk management coverage to producers of covered commodities. Both programs are considered mandatory spending programs funded by the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). There are no participation fees; however, producers must meet certain eligibility requirements to participate and are subject to annual payment limitations. A producer must choose between participating in the ARC or PLC program, but they may not combine the programs as coverage for the same commodity. Producers made a program election in 2019 that remained through 2020, then annually elected a program option in 2021, 2022 and 2023.

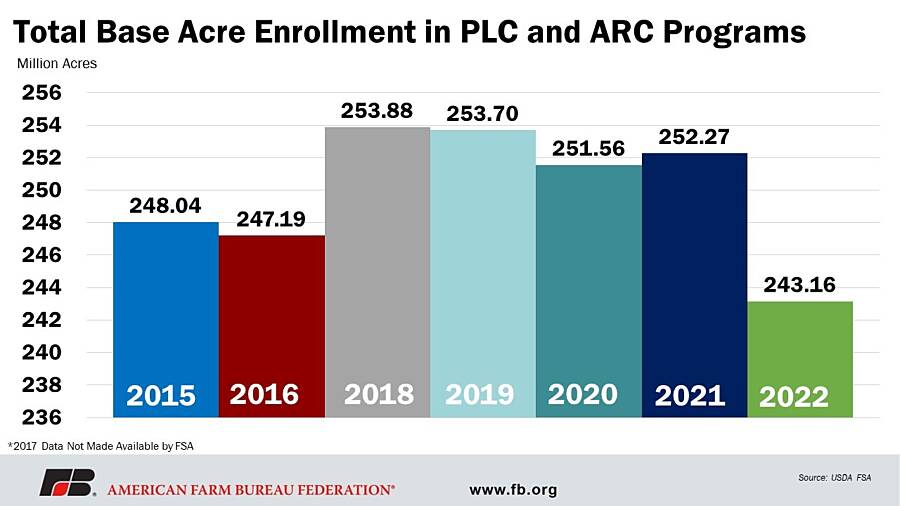

The below figure illustrates the total number of base acres enrolled in the PLC and ARC programs from 2015, the first year the programs were available, through 2022. Data for the 2017 program year is not publicly available from USDA’s Farm Service Agency.

Farmers enrolling in ARC or PLC must make a one-time election on a commodity-by-commodity basis in either ARC-County Option or PLC, or they may enroll all covered commodities in ARC-Individual Coverage. The farm bill also establishes statutory reference prices, which are the published prices for all covered commodities set in statute. PLC uses the statutory reference price as the price floor to trigger a payment. ARC uses the statutory reference price in the guaranteed benchmark revenue calculation.

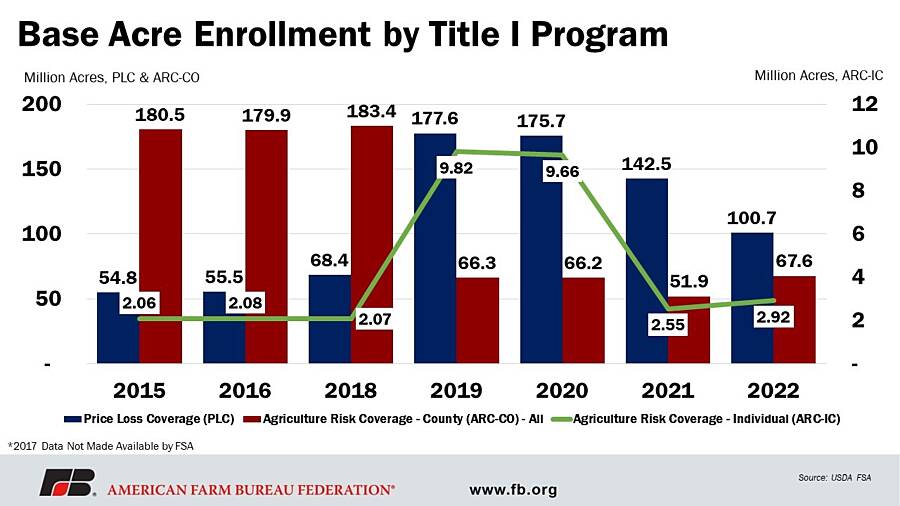

This next figure breaks down how the total base acres are distributed to each program election for PLC, ARC-CO and ARC-IC from 2015 through 2022. Data for the 2017 program year is not publicly available from the USDA Farm Service Agency. Notice the shift farmers make between the 2018 and 2019 program years. When the 2018 farm bill passed, producers had the opportunity to make a program election in 2019 that remained through 2020, then annually elected a program option in 2021, 2022 and 2023, as stated above. As producers prepared to make their program decisions for the 2019 year, the farm economy at the time indicated low prices for a majority of commodities and producers made the shift from ARC-CO to PLC to protect against the low-price expectations on the horizon. As market changes occurred, producers evaluated their program election decisions accordingly for the 2021 and 2022 program years, which allowed them to pick the program that suits their risk management needs.

The covered commodities eligible for ARC and PLC include corn, wheat, soybeans, seed cotton, grain sorghum, barley, rice-long grain, peanuts, oats, sunflowers, canola, rice-temperate japonica, dry peas, lentils, flaxseed, rice-medium grain, safflower, large chickpeas, mustard, small chickpeas, sesame, crambe and rapeseed.

Agriculture Risk Coverage

ARC provides assistance to producers when actual crop revenue for a covered commodity falls below the guaranteed revenue level, which adjusts annually using the Olympic moving average of historic revenues, which removes the highest and lowest values before calculating the average. There are two types of ARC program coverage: county-level coverage (ARC-CO) and individual-level coverage (ARC-IC).

Agriculture Risk Coverage – County Option

ARC-CO triggers a payment when the county-level revenue falls below 86% of the benchmark revenue and the per-acre payment is capped at 10% of the guaranteed level. A payment for ARC-CO is only paid on 85% of a farmer’s base acres. To calculate ARC-CO revenues, the program uses the product of the five-year Olympic moving average of USDA-Risk Management Agency county yields, as opposed to USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service county yields, to capture county-level data, and multiplies it by the higher of the statutory reference price or the marketing year average (MYA) price. The five-year Olympic average drops the highest and lowest values from the sample and averages the remaining three values. For example, the 2019 program year will average prices and yields from 2013 to 2017. Program payments under ARC-CO are capped at 10% of the ARC-CO benchmark revenue. ARC-CO program payments are paid on 85% of the farm’s base acres of the covered commodity.

Previous Market Intel articles reviewed ARC-CO details and payment expectations for the 2019 program year, i.e., ARC-County, A Bird in The Hand for Some in 2019 and What’s in Title I of the 2018 Farm Bill for Field Crops?.

Agriculture Risk Coverage – Individual Coverage

While ARC-CO is a commodity-by-commodity program, ARC-IC is a whole farm program that bases program benefits on individual farm yields for all covered commodities. ARC-IC triggers a payment when farm-level revenues fall below 86% of the farm’s individual revenue benchmark, which is calculated as the farm’s yield for each crop year multiplied by the higher of the statutory reference price or the MYA price. The farm’s individual benchmark revenue is the five-year Olympic moving average of the farm’s benchmark revenue. Payments for ARC-IC are made on 65% of the farm’s base acres and are capped at 10% of the farm’s benchmark revenue.

Price Loss Coverage

PLC provides assistance to producers when the national market price for a covered commodity falls below the effective reference price and triggers a payment of the difference between the MYA price and the effective reference price attributed to a producer’s base acres and payment yields, i.e., when the price of a commodity falls below a specific price floor. For example, a $3.30 MYA price for corn is below the effective reference price of $3.70 and would trigger a program payment of 40 cents per bushel. The effective price equals the higher of the MYA or the national average loan rate for the covered commodity.

A new feature in the 2018 farm bill is a floating reference price in PLC. Under a floating reference price, the effective reference price allows for upward fluctuation of the reference price in times that historic price averages are higher than the statutory reference price for the covered commodity. The effective reference price adjusts annually based on comparing the statutory reference price to 85% of the five-year Olympic moving average of the MYA price, selecting the higher one, then comparing it to 115% of the reference price and picking the smallest.

Like ARC-CO, PLC program payments are made on 85% of the farm’s base acres and the farm’s PLC program yield. Farm owners had the opportunity in 2020 to voluntarily update PLC yields of each individual covered commodity on their farm. The updated yield is equal to 90% of each covered commodity’s 2013-2017 simple average yield, but a yield floor equal to 75% of the county yield is in place to address any poor crop yields in the sample period.

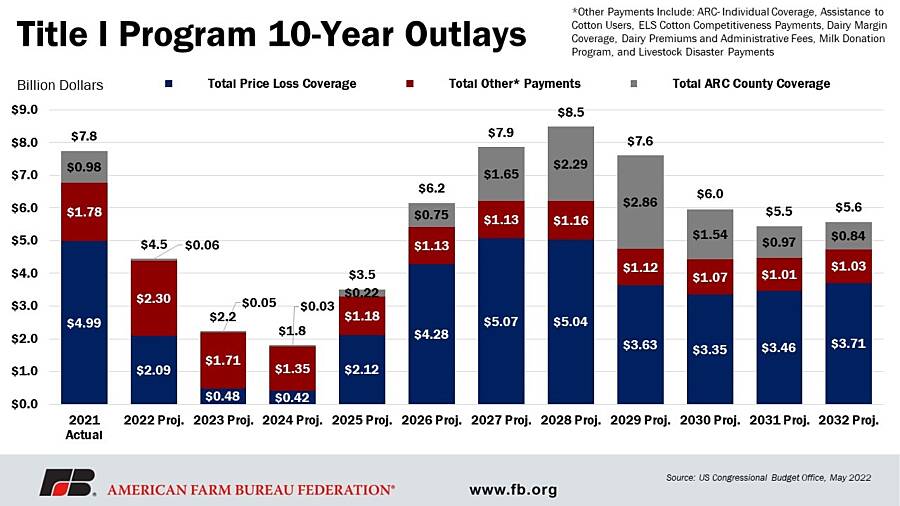

The Congressional Budget Office published its forecasts for the costs of these Title I programs and others in May 2022. These forecasts are made based on the assumption that the policies in the farm bill do not change and include assumptions for the farm economy collected from other agencies, non-government economists and market forecasts. PLC was the most costly Title I program in 2021 and is anticipated to continue to be the most costly program through the 10-year projections. The cost of the PLC programs is followed by the mix of payments associated with other Title I programs, which include ARC-Individual Coverage, Assistance to Cotton Users, ELS Cotton Competitiveness Payments, Dairy Margin Coverage, Dairy Premiums and Administrative Fees, Milk Donation Program, and Livestock Disaster Payments. The ARC-CO is not expected to be as costly as the others listed, however it is anticipated to increase in projected outlays starting in 2026 through 2032, likely due to yield fluctuations and other price variations already built in with PLC estimates.

The final figure displays the most recent Congressional Budget Office forecasts for the costs of these Title I programs and others.

Marketing Assistance Loan Program

Marketing assistance loans provide producers interim financing at harvest time to meet cash flow needs and to delay the selling of the commodity until more favorable market prices are available given prices are typically low at harvest time. The commodity is held as collateral for the loan.

A nonrecourse marketing assistance loan can either be repaid or the producer can redeem it by delivering the agricultural commodity that was pledged as collateral to the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) as full payment for the loan upon maturity. A recourse marketing assistance loan is also available. These could be used for commodities that may be of lower quality, such as a situation of high moisture levels upon delivery, or commodities harvested as other than grain, or for contaminated commodities that are still within merchantable levels of tolerance. Essentially, the commodity is still good, but falls outside the parameters that define it as the standard marketable commodity. These recourse marketing assistance loans can only be repaid at principal plus accrued interest.

Non-recourse marketing assistance loans are available for producers of wheat, corn, grain sorghum, barley, oats, upland cotton, extra-long staple cotton, long grain rice, medium grain rice, soybeans, sunflower seed, rapeseed, canola, safflower, flaxseed, mustard seed, crambe, sesame seed, dry peas, lentils, small chickpeas, large chickpeas, graded and nongraded wool, mohair, unshorn pelts (eligible for a loan deficiency payment only), honey and peanuts.

Provisions in the 2018 farm bill specify that producers may repay market loans, under certain circumstances, at less than the principal amount plus accrued interest and other charges. Alternatively, provisions specify that, in lieu of securing a marketing assistance loan, producers may elect for a loan deficiency payment (LDP). An LDP is the difference the producer would have received if a loan was repaid at the lower market price, a direct benefit that does not need to be repaid. Both of these programs were created to minimize potential delivery, storage and related costs of agricultural commodities to the CCC, and in turn the taxpayer. They also aid the market in avoiding discrepancies across states and counties and allow U.S. produced commodities to be marketed freely and competitively.

Summary

Risk management tools like these shallow-loss coverage programs are vital to farmers and ranchers being able to mitigate the volatile nature of farming. The 2014 farm bill created the Agriculture Risk Coverage and Price Loss Coverage programs, and the 2018 farm bill reauthorized and strengthened them. While farmers and ranchers have faced unprecedented circumstances the past few years, from record prevented-plant acres in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 to record-high input costs and now inflation, the one thing that has stayed consistent is the need for a variety of risk management options like ARC, PLC and marketing assistance loans that fit farmers’ and ranchers’ needs. As 2023 farm bill discussions continue, prioritization of risk management tools, and the necessary funding to provide these tools, remains important for farmers and ranchers.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL