Inflation and the Banks

photo credit: Getty

Roger Cryan

Former AFBF Chief Economist

Last week, two banks were in the process of collapsing, and state and federal regulators took them over.

On Sunday, the Federal Reserve Bank announced more liberal lending to all banks to help them weather the decline in the prices of bonds they hold as bank reserves.

On Monday, President Biden announced an unprecedented bailout for the depositors of two collapsed banks.

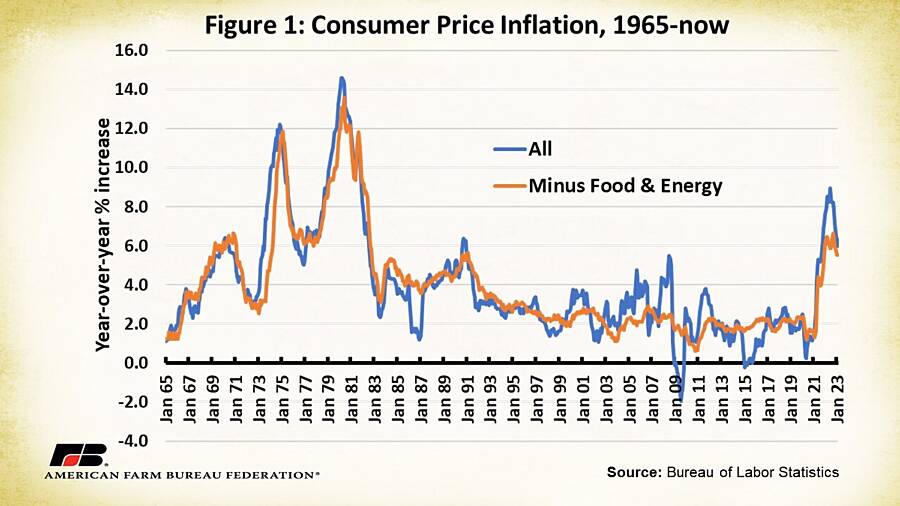

On Tuesday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that consumer prices in February were 6.0% higher than a year ago, the lowest year-over-year inflation rate since September 2021, but still higher than any month before that, going back to December 1990. So-called “core inflation” (inflation minus food and energy – whose prices matter but move more erratically than other prices) was 5.5%, also the lowest since (December) 2021 and also higher than any other month in over 30 years. February’s month-over-month core inflation of 0.5% is higher than any of the last four months.

How are these related?

The inflation of 2021 and 2022, as we have talked about before, was caused by the massive amount of new money created by the Federal Reserve Bank (“the Fed”) in 2020 and 2021. The Fed lent trillions of dollars to banks at near-zero interest rates and purchased trillions of dollars in government-backed securities.

This recent modest slowing of inflation is the beginning of the price response, with a similar lag, to the Fed’s tightening of the money supply, by selling some of those securities and by aggressively raising the interest rates they charge banks.

That is, the Fed has followed an unprecedented 40% increase in the money supply in just 2 years with a 2½% decline in the money supply in the 9 months ending in December, which is already unprecedented in the 50+ years since the dollar stopped being tied to the value of gold, and the largest decline in the money supply since 1937, when tight money policy reignited the Great Depression.

The good news is that this dramatic reversal of money supply growth should be sufficient to rein in inflation over the next 6 to 12 months, given the actions that have already been taken and the time required to see their full effects: just as inflation took 12 months and more to show up after the Fed’s expansionary policies began, so does its contractionary effort take 12 months and more to be fully felt in the inflation rate.

The bad news is that the Fed no longer believes that the money supply is significant to inflation, but believes that it must slow the economy until inflation is reaches the Fed’s target of 2%. The result is that the Fed continues to raise interest rates with the specific intent of slowing the economy, and only a clear immediate return of inflation to (or toward) the 2% target is likely to stop them.

Based on statementsby the Fed’s chair, Jerome Powell, next week’s meeting of the Fed’s Open Market Committee was expected to bring another aggressive rate increase of one-half percent, which would have brought the effective rate the Fed charges banks to over 5%, after sitting at near zero for much of the last decade.

The only reason that this rate increase may be a quarter percent increase is because the Fed seems shaken by the banking crisis that their rate increases have triggered since the Chair’s earlier statement.

Two banks, the Silicon Valley Bank in California and Signature Bank in New York, were closed and taken over by regulators last week. Banks generally have been squeezed by rising Fed interest rates and depositor withdrawals to spend down balances built up during the peak of the Covid pandemic, when the government was sending out big checks to people who had nothing to spend them on. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, the rising interest rates caused the short-term value of bonds they held to go down, and the bank became arguably insolvent, in the sense that they couldn’t sell those bonds now for enough to cover withdrawals, and the instant communication of that among their high-tech startup customers led to a very fast run on deposits, accelerated by digital banking which allows millions to be moved to another bank with a phone app. Signature Bank, which had been heavily involved in cryptocurrency banking, in addition to traditional banking, had a similar run apparently based in part on depositor panic caused by the troubles of Silicon Valley Bank.

The government response included two major actions, in addition to taking over the two banks. First, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which normally insures bank deposits up to $250,000 guaranteed all deposits in these two banks, as much as 90% of whose deposits were over that limit and so would have not been insured without that change. Second, the Fed opened up a new facility for banks to borrow at a slightly lower rate against the long-term value of bonds whose short-term value has been cut by the higher interest rate the Fed has imposed on the economy.

So what does this all have to do with inflation?

Good question.

We have established, I hope, that today’s inflation was caused by the Fed’s aggressive expansion of the money supply in 2020 and 2021.

That inflation has created price instability and uncertainty in the economy that has made many investment decisions riskier than they would be if inflation had remained low and stable.

The Fed has addressed inflation, not by returning to a steady and stable growth in the money supply, but by using monetary policy to beat the economy over the head until the economy slows down, based on their belief that this is the best way to control prices. (As we’ve said before, this is like swinging the anvil on the hammer, rather than the other way around.) In the past, the Fed would raise interest rates reluctantly as a way slow growth in the money supply (especially before selling off bonds was understood as a good alternative); now, the Fed is raising interest rates explicitly to slow demand in the economy.

That intention of slowing the economy also creates risk and uncertainty in the economy, including banks: no-one knows what the Fed will do. (One possibility is that the Fed keeps raising rates to over 6%, until the inflation reduction that is already in the pipeline shows up in another 6 to 8 months.) For the nearly forty years though 2019, by contrast, Fed policy had been remarkably stable and predictable, to the benefit of the entire economy.

As mentioned above, the Fed’s interest rate increases have created pressures on banks by depressing the current market value of some of the relatively conservative assets they hold, ironically, to meet regulatory requirements.

The good news in the short run, for farmers and depositors, is that the government’s quick action should shore up otherwise healthy banks across the country, including your community bank. The message from agricultural lenders at community banks I spoke to this week is that, while interest rates are higher and so is credit more expensive, access to that credit won’t be a problem in 2023, especially given the strong outlook for the farm economy. Farm balance sheets are strong, on average, and 2023 looks to be another good year. The high cost of credit may slow expansion of production, and that caution in borrowing is probably prudent.

Community banks also tend to avoid the risky businesses like crypto-currency and high-risk startups, and they welcome depositor visits to the bank and scrutiny of their annual reports for reassurance.

And the government seems to have guaranteed all deposits in all banks, so that shouldn’t be a concern for depositors either.

Whether that is a good long-term policy for the financial system is probably something we will be talking and thinking about for some time. The FDIC relies on healthy banks to pay into a pool, and uses that pool to guarantee depositors. Insuring all deposits could mean responsible banks will be paying more for the action of irresponsible (and unlucky) banks, and doing so in an economic environment made more risky by the Fed’s new approach to its job.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL