Record Milk Production, Shrinking Herd Pipeline

photo credit: AFBF

Daniel Munch

Economist

Key Takeaways

- Record milk production masks underlying herd strain. U.S. milk output is reaching record levels, but those volumes reflect short-term herd management decisions rather than durable expansion.

- Herd signals are increasingly distorted. Historically low culling, an aging cow herd and a shrinking pool of replacement heifers mean milk pricing is no longer the primary signal guiding herd decisions, limiting the industry’s ability to adjust gradually to changing market conditions.

- Beef-on-dairy economics are tightening the replacement pipeline. Strong beef prices and beef-on-dairy premiums have boosted near-term revenues but reduced the number of dairy-bred heifers available to sustain future milk production.

- Global supply growth is pressuring prices while boosting exports. Expanding milk production in the U.S. and other major exporting regions has weighed on farm-level prices even as it has made U.S. butter and cheese highly competitive abroad, supporting record export volumes that do not fully offset on-farm margin pressure.

U.S. milk production is setting records, but those volumes are sending increasingly misleading signals about the health of the dairy sector. Milk cow inventories are at their highest level since 1993, even as replacement heifer numbers have fallen to their lowest point since 1978 — a divergence driven by short-term herd management decisions rather than true expansion.

Strong beef prices and elevated beef-on-dairy premiums have encouraged farmers to keep cows in production longer and shift breeding toward beef genetics. While that strategy has provided an important income offset through calf sales, it has also inflated milk supply and dampened farm-level milk prices, worsening returns on the milk side of the business even as total farm revenue appears more resilient.

Lower milk prices have improved U.S. competitiveness abroad, supporting record cheese and butter exports in 2025. But this export-driven relief masks a growing imbalance at home: today’s production gains rely on older cows and a shrinking replacement pipeline. This Market Intel examines how current supply strength is amplifying price pressure, distorting market signals and setting the stage for tighter and potentially more volatile milk markets ahead.

Herd Dynamics Are Distorting Market Signals

U.S. dairy herd metrics are increasingly moving out of sync, complicating how current market signals should be interpreted. In a typical expansion cycle, rising cow numbers are accompanied by growing replacement inventories and elevated culling when economic incentives shift. Today’s environment looks different: cow inventories are high and culling remains historically low – but at the same time, the replacement pipeline is contracting.

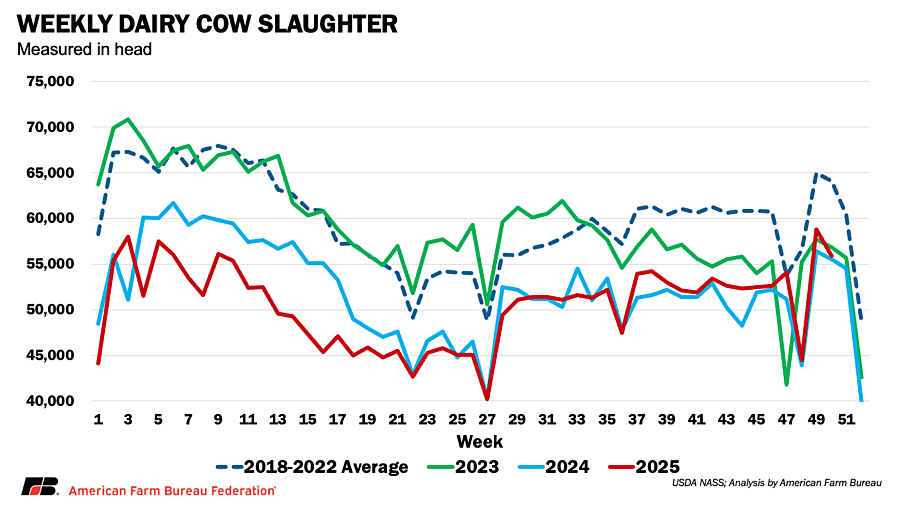

That pattern is evident in slaughter data. After months of comparatively low dairy cow culling, slaughter volumes in the final weeks of 2025 moved closer to recent norms. Even so, cumulative dairy cow slaughter through the first 50 weeks of 2025 totaled 2.53 million head, the lowest level in more than a decade, down from 2.61 million in 2024 and well below the roughly 3 million head slaughtered annually in most prior years. In short, fewer milk cows have been exiting the herd.

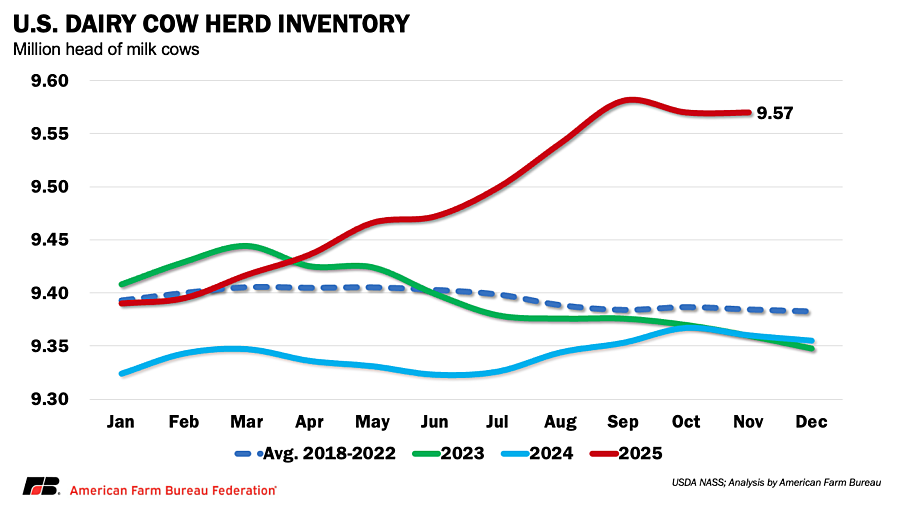

As of November 2025, the U.S. milk cow herd totaled 9.57 million head, the most since 1993, when inventories peaked at 9.58 million head. While cow numbers remain well above recent years, growth has begun to slow, suggesting the current expansion may be losing momentum.

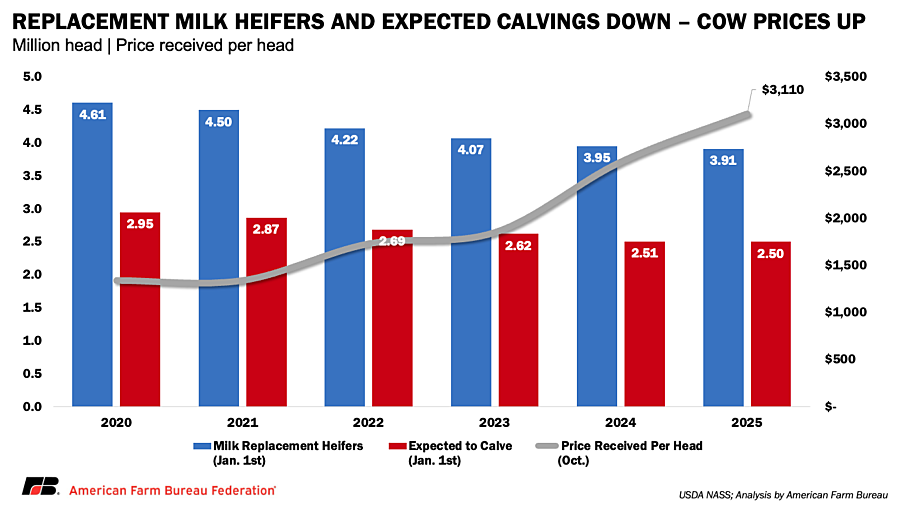

Despite record milk cow inventories, the pipeline supporting those numbers is tightening. According to the January Cattle Inventory report, milk replacement heifer inventories fell to 3.91 million head in 2025, the lowest level since 1978 (3.89 million). More concerning for the medium-term outlook, the number of dairy replacement heifers expected to calve in the future declined to roughly 2.5 million head, the lowest level since USDA began reporting the series in 2019 and well below the nearly 3 million head recorded just a few years ago.

Notably, this contraction in replacements has persisted even as culling incentives have strengthened. October data show the price received for milk cows reached a record $3,110 per head, nearly $1,800 higher than just five years ago. Under normal conditions, prices at that level would be expected to accelerate culling, underscoring how unusually tight replacement availability has become.

The key factor behind this tightening replacement pipeline is the continued expansion of beef-on-dairy breeding, which has reshaped heifer availability across the U.S. dairy sector. Elevated beef prices have made crossbreeding dairy cows with beef genetics an increasingly attractive strategy, improving calf values and near-term cash flow, an income boost analysts have estimated at the equivalent of roughly $4 to $5 per cwt of milk. But the tradeoff is fewer dairy-bred heifers entering the replacement pool. As more dairies allocate a growing share of their herd to breeding with beef semen, the biological capacity to rebuild the milk cow herd has narrowed, even as total cow numbers remain historically high. The result is a herd structure that supports milk output in the short run but leaves the industry more exposed to a sharper adjustment if culling accelerates or productivity falters.

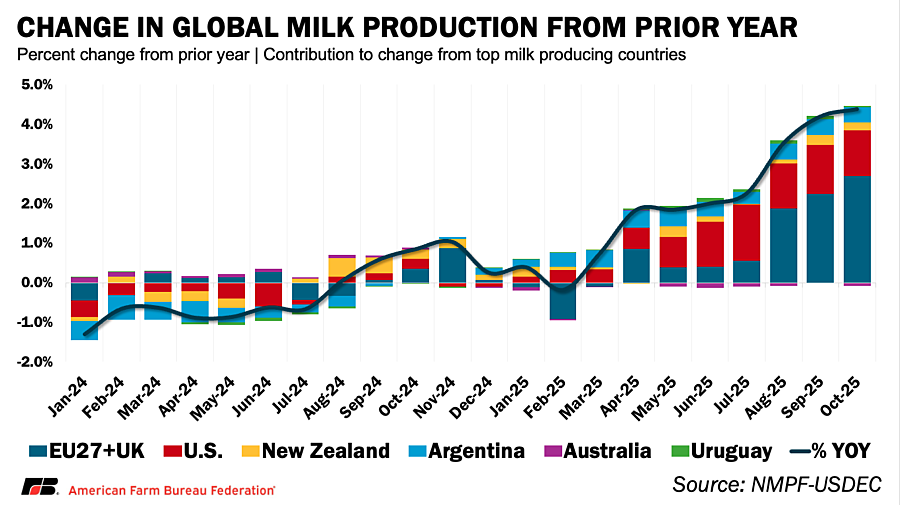

Global Milk Supplies are Expanding Alongside the U.S. Herd

Layered on top of elevated U.S. cow inventories, global milk production has also been accelerating, reinforcing near-term supply pressure across dairy markets. The U.S. is on pace to post record milk production in 2025, with 876 million metric tons produced from January through October, up from 855 million metric tons in 2024 and 859 million metric tons in 2023 — an increase of roughly 2.4% year-over-year. That growth has not occurred in isolation. Other major exporting regions have also expanded output over the same period, adding to global availability. Milk production from the EU-27 plus the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina and Uruguay rose by approximately 1.5%, 2.0%, 9.7% and 6.8%, respectively, compared to the first 10 months of last year. Australia was the lone major producer to post a decline, with output down roughly 6.8% year over year. Across key producing regions, combined milk production increased by roughly 54 million metric tons total, or 2.1%, from January through October 2024, with growth heavily concentrated in the U.S. and the EU27 plus the U.K., which together accounted for the majority of the volume gains.

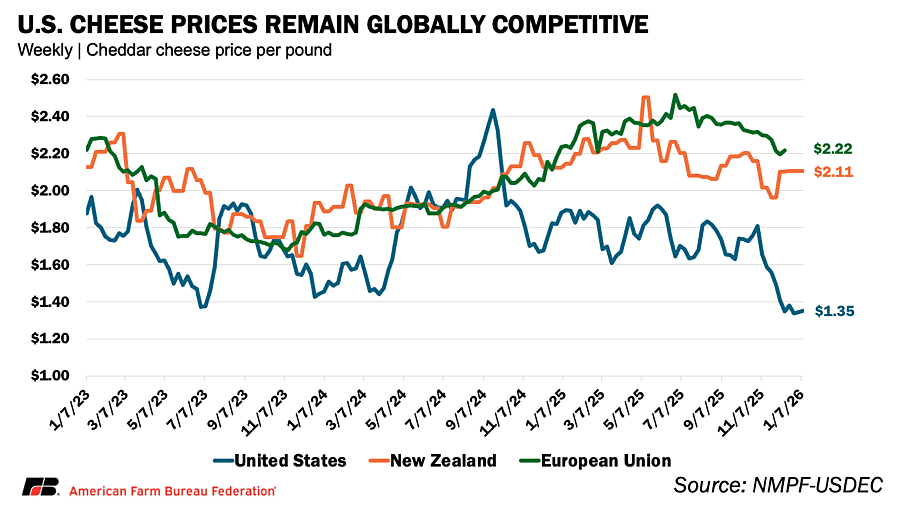

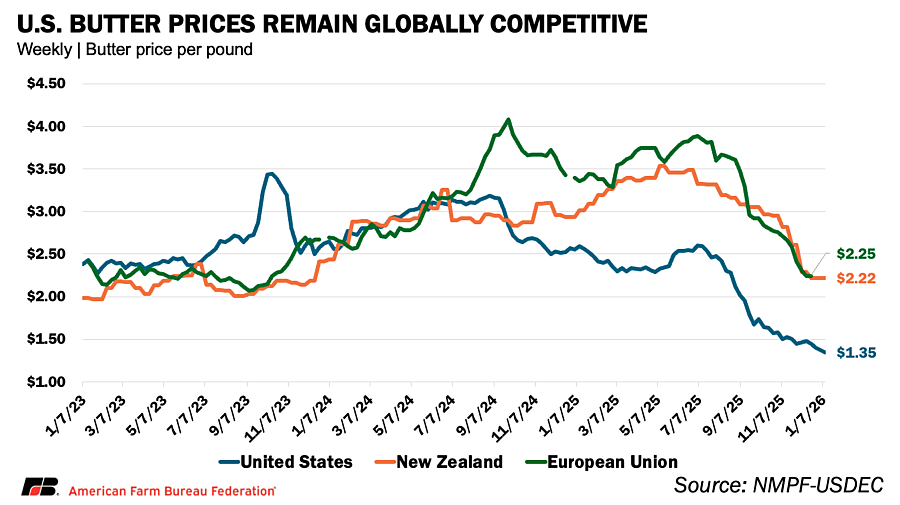

The expansion in U.S. and global milk production has translated into clear pressure on farm-level prices, even as it has materially improved the international competitiveness of U.S. dairy products. The U.S. all-milk price averaged $19.70 per cwt in November 2025, down more than $4 per cwt since January, reflecting the weight of rising supplies. Product markets have adjusted even more sharply. Butter prices fell from roughly $2.55 per pound in early January 2025 to about $1.35 per pound by January 2026, a decline of nearly 47%, while cheddar cheese prices dropped from $1.88 to $1.35 per pound, a decline of roughly 28% over the same period.

While these price declines have strained the milk side of dairy balance sheets, they have strengthened the competitive position of U.S. dairy products abroad. Since October, U.S. cheddar prices have averaged roughly 36% below New Zealand and 42% below the European Union, while U.S. butter prices have been even more discounted — about 73% lower than New Zealand and 68% lower than the EU.

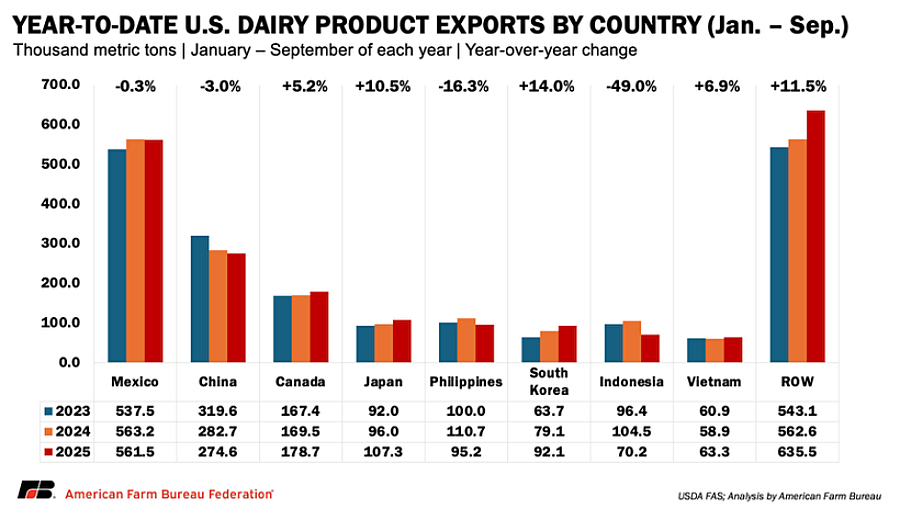

That pricing advantage has supported record U.S. dairy product exports in 2025, with shipments rising from approximately 2.02 million metric tons to 2.07 million metric tons between January and September, an increase of roughly 51,000 metric tons (2.4%) from to the same period in 2024. Even as exports to some major partners, including Mexico and China, softened, gains in Canada, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and a growing number of smaller destination markets more than offset those declines, underscoring how broad-based price competitiveness is reshaping U.S. export flows.

Conclusion

Ample milk supplies in the U.S. and across major exporting regions have kept farm-level prices under pressure while supporting strong trade flows. But the forces behind that supply growth differ by region. Outside the U.S., production gains largely reflect conventional expansion and productivity improvements. In the U.S., by contrast, current milk volumes are being sustained by short-term herd management responses, older cows kept in production longer, limited culling, and breeding decisions that prioritize immediate returns over herd replacement for milk production.

That dynamic suggests milk pricing is no longer the primary signal guiding U.S. herd management. When supply becomes less responsive to milk prices and more constrained by biology, the ability to adjust gradually diminishes. As a result, today’s ample supplies may be misleading about the sector’s underlying flexibility, raising the risk of tighter and more volatile milk markets once herd dynamics begin to turn. The question now is how long milk production can remain elevated before aging cows and a thinning replacement pipeline force a sharper adjustment.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL