Understanding USDA’s New Natural Disaster Relief: Part 2

photo credit: Florida Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Key Takeaways

- USDA has finalized Supplemental Disaster Relief Program (SDRP) provisions for 2023–2024 losses that are not tied to crop-insurance or Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program records. These rules cover loss types that fall outside traditional indemnity programs and were not addressed in earlier SDRP payments.

- Payments for these categories are based on USDA-assigned yields, prices or plant values. This approach applies to uninsured crops, nursery and aquaculture inventory, perennial plants, stored commodities and milk disposal.

- Each loss type uses its own formula built around assigned values rather than farm-level records. County expected yields, USDA-determined market prices, plant values and damage factors shape how assistance is calculated.

- Operations with multiple crops or locations may need to complete several separate calculations. Because assigned values vary by crop and county, diversified farms may see different payment structures across their operation.

Part 1 walked through the SDRP components that rely on familiar records, crop insurance and Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) data, where producers have a clearer sense of how their losses translate into payments. But these shallow-loss pathways capture only part of the picture. A significant share of SDRP Stage 2 is structured around losses that fall outside traditional indemnity systems entirely, and USDA’s decision to build those components around assigned yields, prices or plant values shapes how, and how accurately, those losses are recognized.

This approach does significantly expand eligibility, especially for specialty crops, nurseries, perennial plantings and any operation with uninsured acreage. At the same time, it introduces the greatest variation and complexity within SDRP. Assigned county yields may differ from what growers typically produce; USDA-determined prices may not match the markets farmers faced; and whole-plant values for orchards, vineyards or berry bushes may not reflect the full investment producers have in those plantings. Diversified farms may encounter several distinct calculation methods within a single operation, each built around different assumptions, terminology and documentation needs. And because SDRP covers 2023–2024 disasters, many producers are being asked to reconstruct losses that occurred nearly three years ago — adding administrative burden even as the program aims to fairly and consistently recognize losses across regions and commodities.

Part 2 of this Market Intel series walks through these remaining categories, uninsured crops, value-loss crops, trees/bushes/vines, on-farm storage losses and milk losses, and identifies where USDA’s assigned-value approach provides needed support, as well as areas where the methodology may limit payments or create administrative challenges for producers.

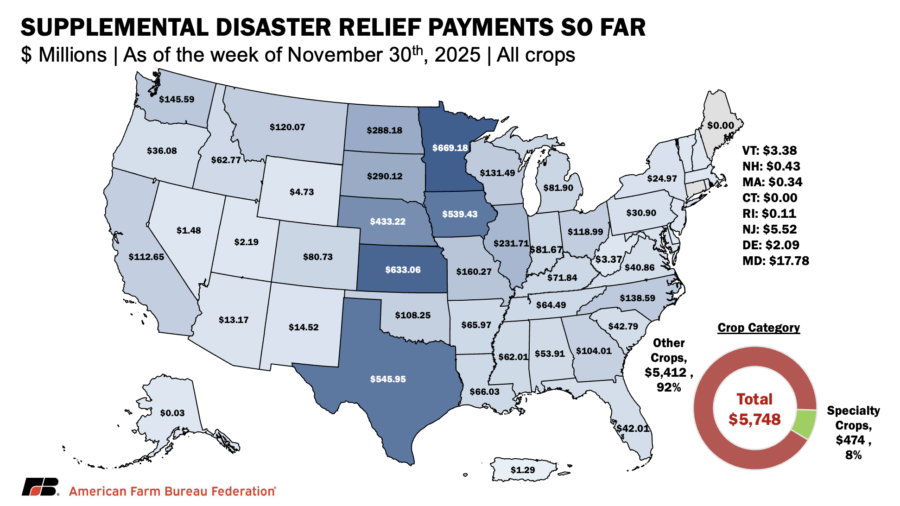

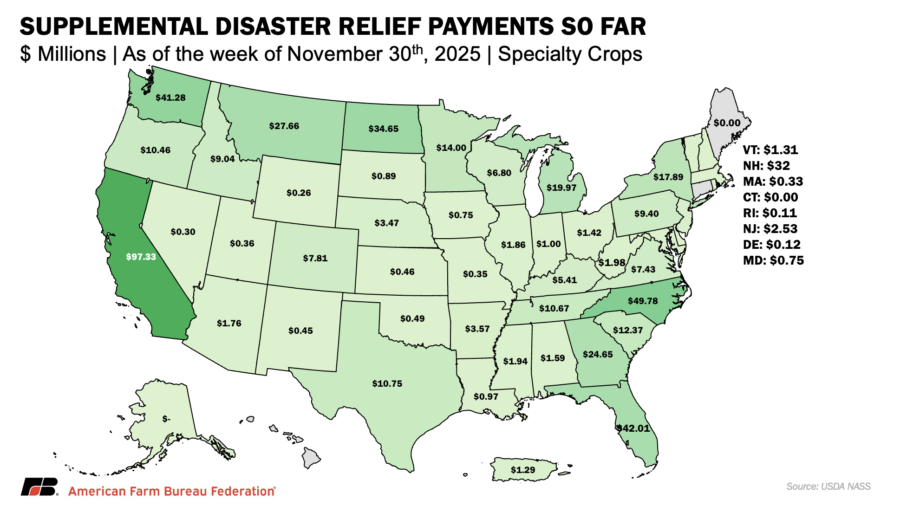

These categories now carry significant weight. As of the week of Nov. 30, USDA has distributed $5.7 billion in SDRP payments through earlier stages. Specialty crops account for $475 million, about 8% of all payments, despite experiencing closer to 20% of total crop-sector natural disaster losses during 2023–2024.

Stage 2, Category 3: Uninsured Crops

This portion of Stage 2 fills what is perhaps the most demanded gap in the remaining SDRP funds, supporting specialty crop producers who have no viable crop insurance or NAP options and therefore suffered losses without any risk management safety net. Despite steady growth in coverage options, large gaps remain: over 43% of fruit and nut acreage and 47% of vegetable and melon acreage are still uninsured by either crop insurance or NAP, leaving many specialty crop producers exposed when disasters occur. One key reason is actuarial soundness or that federal crop insurance must be priced so that premiums and expected losses balance over time, and for many specialty crops there simply is not enough consistent yield and price history to build affordable, sustainable coverage.

Uninsured producers use a fundamentally different equation because USDA must construct an expected value absent any insurance records. SDRP does this by assigning:

- An FSA-determined county expected yield, which may come from National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) county yields, state-level yields scaled to the county, comparable crop proxies or administratively determined yields when no published data exist; and

- An average market price derived by USDA.

The uninsured equation is:

- SDRP liability = Eligible acres x county expected yield x average market price x SDRP factor of 70%

- Calculated loss = (SDRP liability – (production x (1 – quality loss percentage) x average market price x unharvested or prevented payment factor if applicable) – salvage value) x the producer’s share

- SDRP Stage 2 payment = Calculated loss x 35%

As an example, suppose a farmer had 50 acres of watermelons with a 100% share. The county-expected yield for watermelons was 371.67 cwt/acre with an average market price of $22.94 per cwt. The farmer’s production was 12,500 cwt with a quality loss of 3%. The producer harvested the crop and received no salvage value for the crop.

- 50 acres x 371.67 cwt/acre x $22.94 x 0.70 = $298,413.84

- $298,413.84 – (12,500.00 cwt x (1 – 0.03) x $22.94) x 1.00 = $20,266.34

- $20,266.34 x 0.35 = $7,093.22

Because the county-expected yield drives the SDRP liability, assigned yields for crops without published histories may differ from farm-level performance. The rule also requires calculations to be completed on a crop-by-crop basis, with each crop tied to its own county-specific expected yield and USDA-assigned price. For diversified specialty crop operations, this can involve multiple SDRP calculations using different county factors, quality adjustments and price assumptions. Producers with acreage in more than one county must apply the applicable parameters for each county where production occurred, which increases the number of calculations required as operations become more geographically diverse.

Stage 2, Category 4: Value Loss Crops (Including Ornamental Nursey & Aquaculture)

Assessing loss for value-loss crops, such as ornamental nursery and aquaculture, is significantly different than for yield-based crops. Unlike field crops that are harvested once a year, these operations buy, grow, sell and replace inventory continuously. As a result, the value of plants, fish or stock on hand can change quickly from week to week due to normal sales, replanting and production cycles and not just because of a disaster. As a result, Stage 2 payments for value loss crops are based on inventory before and after the qualifying disaster event.

SDRP Stage 2 payment = (((Dollar value before disaster x SDRP factor of 70%) – Dollar value after disaster) x unharvested payment factor if applicable – salvage value) x producer’s share x 35%

As an example, suppose a farmer had a nursery crop with a $70,000 value immediately before the disaster and a $20,000 value immediately after the disaster. The grower received no salvage value for the crop and has a 100% share. The payment would be calculated as follows:

(($70,000 x 0.70) – $20,000) x 1.00 x 0.35 = $10,150

Stage 2, Category 5: Trees, Bushes and Vines

For perennial crops, the “crop” is the tree, bush or vine itself, not the fruit or nuts it produces. USDA assigns a value per plant according to species and growth stage and applies a damage factor to reflect the proportion of value lost when a plant is partially damaged but not destroyed. All tree, bush and vine payments use a fixed 70% SDRP factor. Losses are calculated as:

- Expected value = (Number of trees destroyed + number of trees damaged) x price determined by FSA

- Actual value = Expected value – (Number of trees destroyed x price determined by FSA) – (number of trees damaged x damage factor x price determined by FSA)

- SDRP Stage 2 payment = (((Expected value x 0.70) – actual value – salvage value) x producer’s share + insurance premium and administrative fees if applicable) x 35%

Example: A freeze destroys 40 blueberry bushes and damages 260. FSA values each bush at $28 with a 0.60 damage factor. The producer has a 100% share and no salvage value.

- Expected value: (40 destroyed + 260 damaged) × $28 = $8,400

- Actual value: $8,400 − [(40 × $28) + (260 × 0.60 × $28)] = $2,912

- SDRP Stage 2 payment: [((Expected value × 0.70) − actual value − salvage value) × share] × 35% = [($8,400 × 0.70 − $2,912 − $0) × 1.00] × 0.35 = $1,038.80

On-Farm Stored Commodity Loss Program (OFSCLP)

The disaster assistance also includes an on-farm storage loss program for grain, oilseed, hay and other eligible commodities that were lost as a direct result of damage or destruction to on-farm storage structures. Unlike other Stage 2 components, OFSCLP does not rely on assigned yields or quality adjustments; payments are based solely on the quantity lost and a NASS-determined market price. The equation is comparatively simple:

OFSCLP Payment = (Lost Quantity × NASS Price × 0.75 × Share) − Salvage

A corn producer loses 1,000 bushels to a bin collapse and is able to recover $500 in salvage value from damaged grain, with a NASS price of $3.60 per bushel, receiving:

($3.60/bushel x 75% OFSCLP factor x 1,000 bushels) - $500 salvage = $2,200

As with other components, payments remain subject to SDRP’s payment limitations and adjusted gross income (AGI) rules.

Milk Loss Program (MLP)

MLP compensates dairy operations for milk dumped or removed from the commercial market in 2023 or 2024 due to a qualifying disaster event. Payments are calculated using the farm’s average daily production from the base period, multiplied by the number of affected cows and days of loss and the net pay price for the claim month.

Under the rule, the eligible hundredweight is calculated as:

- Per-cwt pay price = (Gross pay price from the milk marketing statement − hauling rate − $0.15 promotion fee).

- Eligible milk (cwt) = [(Base-period pounds-per-cow average daily production × number of milking cows in claim period × number of days milk was dumped) ÷ 100].

- Final MLP payment = Eligible milk (cwt) × per-cwt pay price × 75%.

Example: Consider a mid-sized dairy that averaged 68 pounds per cow per day during the base period and had 150 milking cows during a qualifying storm that blocked milk pickup for five days. The farm’s gross pay price during the claim month was $20.10 per cwt, with a 45 cent hauling rate and the standard 15 cent promotion fee, yielding a net pay price of:

- Per-cwt pay price: $20.10 − $0.45 − $0.15 = $19.50 per cwt

- Eligible milk: [(68 lb × 150 cows × 5 days) ÷ 100] = (51,000 lb ÷ 100) = 510 cwt

- Final MLP payment: 510 cwt × $19.50 = $9,945× 0.75 = $7,458.75

In this example, the dairy lost nearly 51,000 pounds of marketable milk but receives $7,458 under MLP to offset part of the economic impact when milk hauling and processing were disrupted.

Program-Wide Requirements and Limitations

Across all components, SDRP applies standard USDA compliance rules. Farmers must have all required eligibility, AGI, conservation, entity and customer-record forms on file with FSA; certify acres, production and disaster impacts; and avoid duplicate benefits for the same loss. The rule also requires documentation of the disaster event and that losses occur within an eligible disaster window or county declaration. Producers who receive SDRP payments must also obtain crop insurance or NAP coverage of at least 60% for the next two available years for the same crop and county or repay the assistance with interest. Payment limits mirror ERP and apply cumulatively across Stage 1 and Stage 2, and payments may be prorated if funding is insufficient.

Conclusion

SDRP’s remaining Stage 2 categories broaden disaster assistance, reaching uninsured crops, value-loss operations, perennial plantings, on-farm storage losses and milk disposal. These components capture many of the losses that fell outside traditional indemnity systems, and for some producers, particularly specialty crop, nursery and diversified farms, they represent the only available pathway to recover 2023–2024 impacts.

At the same time, the structure USDA adopted introduces important practical considerations. Assigned county yields, plant values and average market prices can differ from farm-level experience, and diversified operations may have to work through multiple formulas within a single application, each with its own assumptions, terminology and documentation needs. Because SDRP covers disasters that occurred in 2023 and 2024, producers are also being asked to assemble records and certify losses from earlier seasons, which adds an additional layer of complexity to the process.

Even so, SDRP remains a critical opportunity for growers to recover losses that existing risk management tools did not capture. Delivering that assistance will require significant effort not only from farmers assembling documentation, but also from hardworking FSA county staff who will be processing, validating and cross-checking highly detailed applications across multiple program categories. Early coordination with FSA, careful documentation and an understanding of how USDA applies these assigned values will be essential for producers to maximize the support available through this final tranche of the American Relief Act’s disaster authority.

Farmers must submit SDRP applications for all 2023–2024 losses by April 30, 2026, with separate applications required for each crop year. Farmers can apply by submitting the appropriate SDRP forms to any local FSA county office, even if their operation spans multiple counties. Behind that single application, FSA will apply county-specific expected yields, prices and disaster designations for each county where the crop was grown, based on the producer’s acreage reports and insurance records. FSA will announce sign-up start dates for each application group, and producers may find these dates and additional instructions at their county office or on USDA’s SDRP program webpage.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL