Wheat Exports: The Balancing Act of U.S. Wheat

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

Trade is a hot topic with a lot of uncertainty. Trade policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., will impact farmers and ranchers in the countryside. This Market Intel is part of a series exploring agricultural trade, including the potential impacts of trade policy changes.

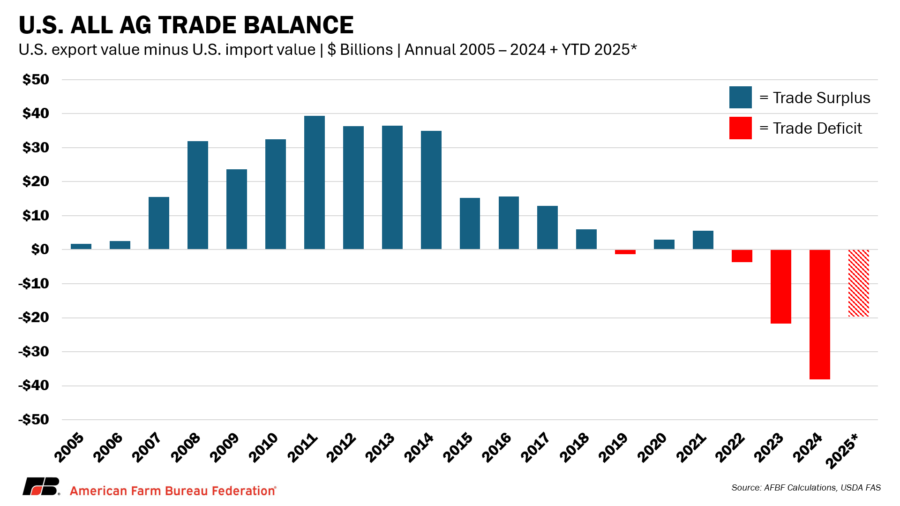

Between January and April of this year, the United States imported $78.2 billion worth of agricultural products, the highest value on record. Over the same period, U.S. agricultural exports totaled just $58.5 billion, resulting in a record-setting agricultural trade deficit of nearly $20 billion in just the first four months. However, U.S. wheat exports are projected to reach their highest level in five years during the 2025/26 marketing year. This rebound underscores the importance of foreign market access for wheat farm profitability, the potential for growth under today’s global supply conditions, and the ongoing risks from price pressure, weather volatility and unresolved trade barriers.

Agriculture Trade Balance

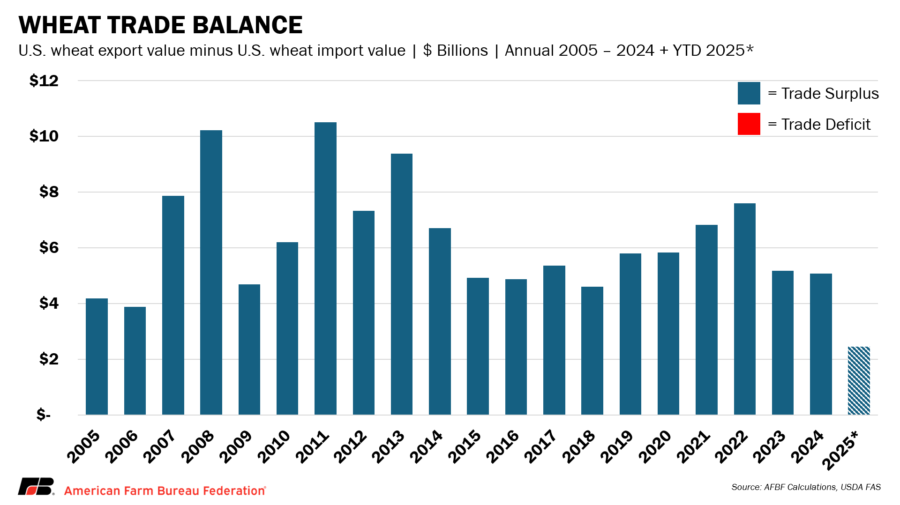

While the overall agricultural sector has slipped into a widening trade deficit, wheat remains one of the few U.S. commodities that consistently generates a trade surplus. U.S. wheat exports totaled 826 million bushels in 2024/25 and USDA’s August World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) projects 850 million to 875 million bushels in 2025/26.

Agricultural trade is vital as agriculture exports bring in billions in revenue, support rural jobs and help stabilize the farm economy. In 2023, for every $1 of agricultural exports, over $2 is generated in the U.S. economy. For producers, the wheat trade surplus is proof that U.S. farmers can compete globally when markets are open and supply conditions align. Maintaining and expanding access to international markets is essential for wheat to continue offsetting broader agricultural trade deficits.

U.S. Wheat Profile

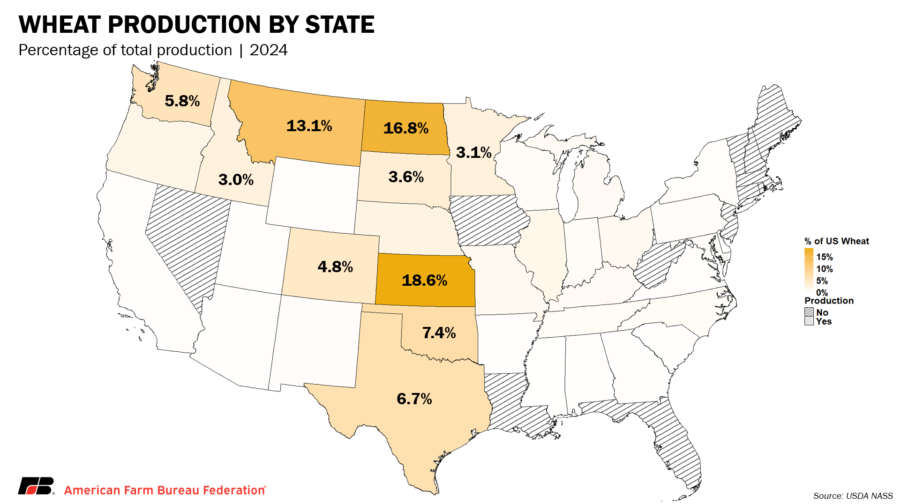

Wheat is grown in nearly every U.S. state, but most production is concentrated in the Great Plains, Pacific Northwest and parts of the Southeast. Winter wheat accounts for 70% of total output on average, planted in the fall and harvested in summer.

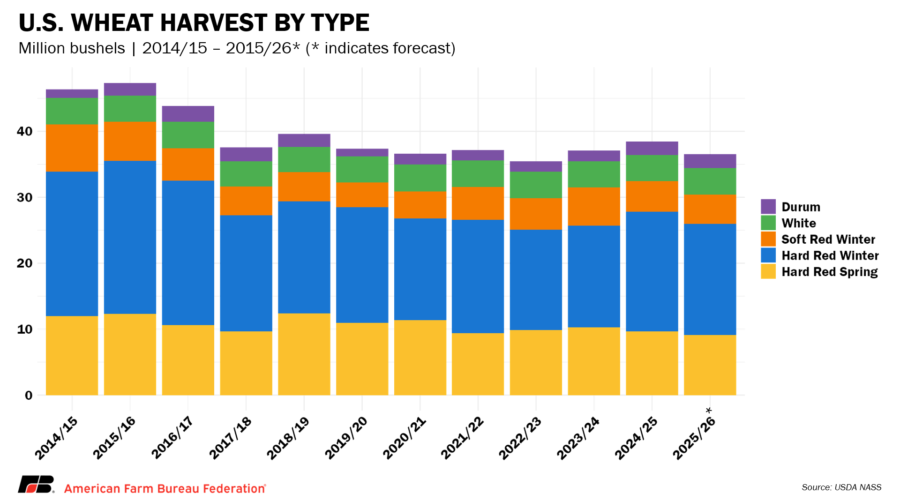

The five classes of U.S. wheat serve different markets and regions. Hard red winter wheat makes up about 40% of production, grown mainly in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas, and is used primarily for bread. Hard red spring wheat accounts for roughly 20 to 25%, produced in North Dakota, Montana and Minnesota, and is also used for bread and rolls due to its higher protein. Soft red winter wheat, about 20% of production, is grown across the eastern Corn Belt and Southeast and is used in cakes, cookies and crackers. White wheat, concentrated in the Pacific Northwest and making up about 12.5% of production, is used for Asian noodles and some breads. Durum wheat, the smallest class at about 4% of production, is grown in North Dakota, Montana and Arizona and is used mainly for pasta.

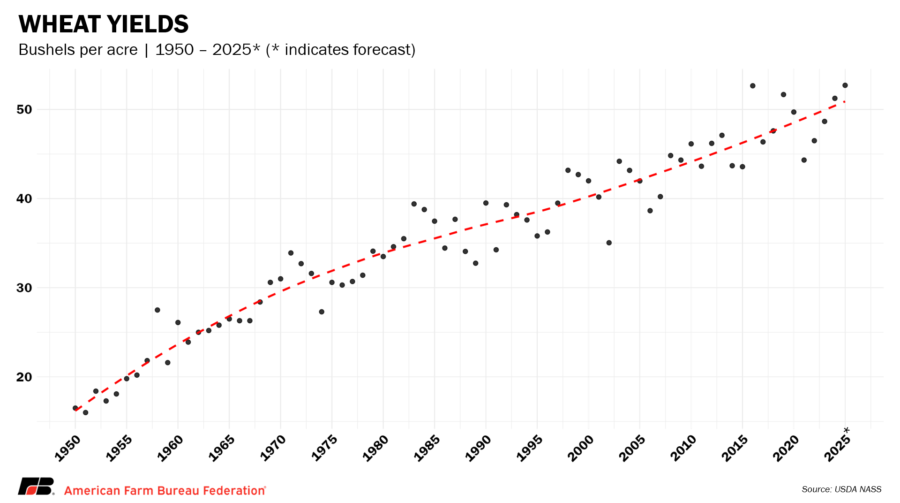

Historical Trends: Shrinking Acreage, Higher Yields

In 2024/25, U.S. farmers harvested 38.5 million acres of wheat, producing 1.97 billion bushels. USDA projects that there will be 36.6 million acres of wheat harvested in 2025/26 with approximately 1.93 billion bushels. While wheat remains the nation’s third-largest field crop behind corn and soybeans, planted acres have declined dramatically. Since 1981, wheat acreage has dropped by more than 40 million acres, and production has fallen by nearly 800 million bushels, even with improved yields. This acreage loss can be tied to changes in farm legislation that allowed farmers more flexibility when choosing crops and advances in seed genetics that improved production in other row crops. Many producers have shifted to corn, and soybeans as technology advanced.

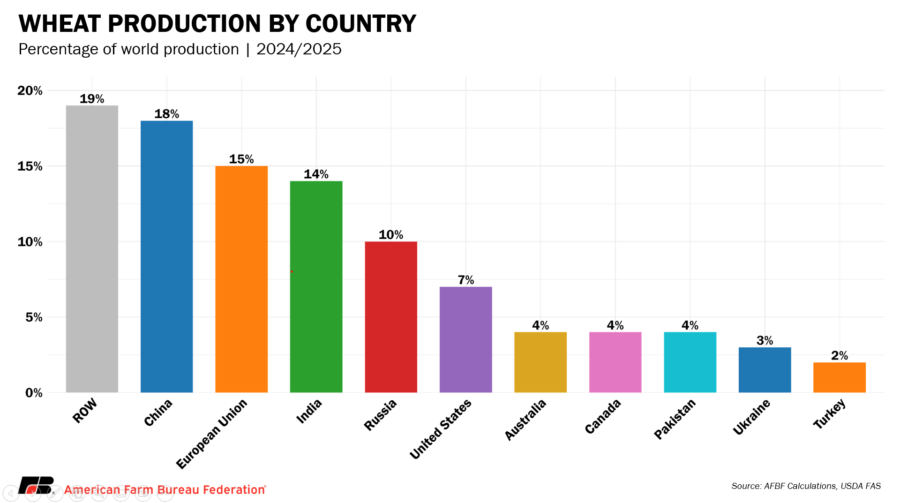

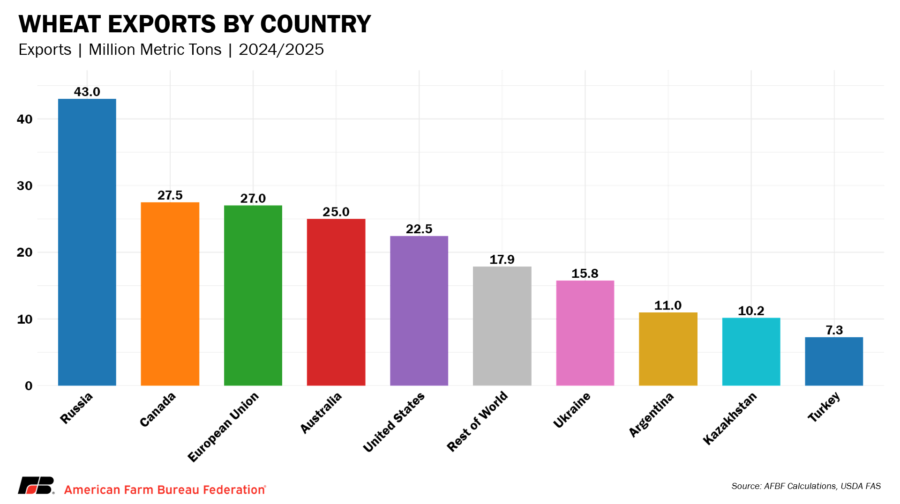

U.S. Wheat in the Global Export Market

The United States remains one of the world’s leading wheat exporters, shipping nearly half of its production abroad. Exports represented 42% of U.S. wheat production in 2024/25 and are projected to reach 44% in 2025/26. The U.S. share of global wheat trade has fallen to about 11%, down from an average of 25% between the 2001/02 and 2005/06 marketing years.

According to USDA’s August 2025 WASDE, global wheat supplies are projected at nearly 1.07 billion metric tons, down 2.5 million from July, with smaller crops in China, Brazil and Argentina more than offsetting gains in the European Union. Global consumption is forecast slightly lower on reduced feed use in Asia, while trade is raised to 213.5 million tons on stronger U.S. exports. Ending stocks are projected at 260.1 million tons, the lowest since 2015/16.

For U.S. wheat, tighter world stocks create market opportunities in Latin America, the Middle East and Asia, where buyers are seeking reliable suppliers. However, a strong European Union harvest adds competitive pressure, and low farmgate prices at home continue to squeeze margins. Even with export demand improving, profitability on U.S. farms is far from assured.

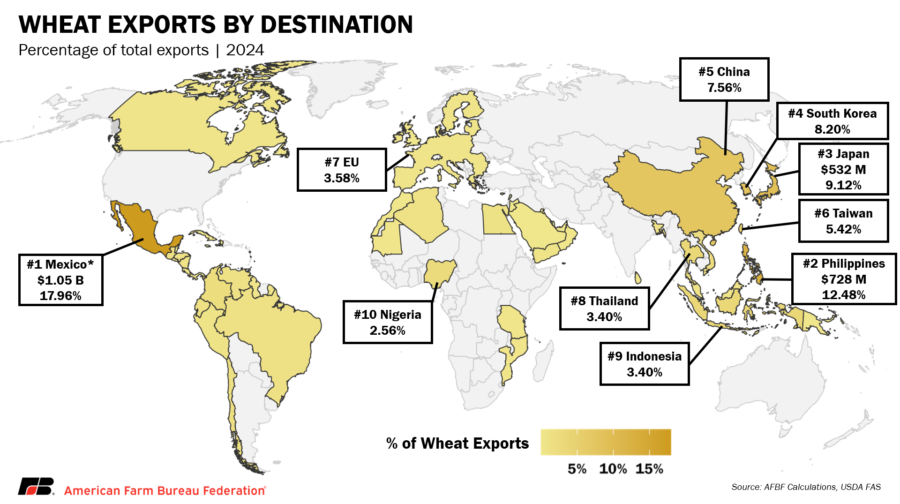

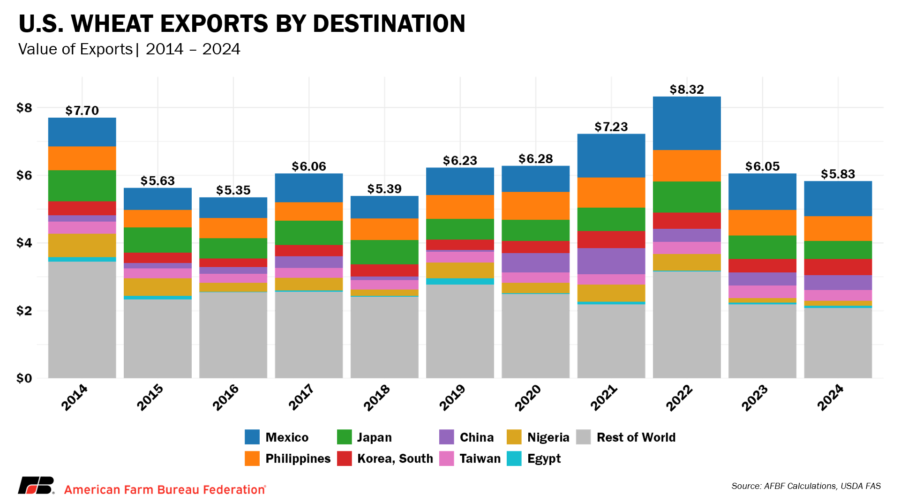

Destinations for U.S. Wheat

U.S. wheat exports are spread across more than 70 countries, but sales remain concentrated in a few key markets. In 2024, Mexico was the top buyer at $1.05 billion, nearly 18% of total exports. The Philippines followed with $728 million, or 12%, while Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan rounded out the top six markets. Together, these destinations account for more than half of all U.S. wheat exports.

Over the past decade, Asia has become the main growth driver for U.S. wheat exports. Indonesia, Bangladesh and Vietnam have sharply increased purchases. A mix of stable anchors, like Japan and the Philippines, and new growth markets highlights both opportunity and risk. Concentration among a handful of buyers makes trade vulnerable to policy and local supply shifts, but rising demand in Asia and Africa shows U.S. wheat is maintaining and even expanding its foothold abroad.

Risks and Outlook

The short-term outlook for wheat exports is bright, but risks remain. Ongoing competition from the European Union and Black Sea region will weigh on prices. Shrinking acreage in the United States could limit exportable surpluses in future years. Even so, global supply conditions are leaning in favor of U.S. farmers. Lower crops in Argentina, Brazil and Ukraine are creating new openings, while global wheat stocks are at their lowest in more than a decade. If U.S. farmers can maintain acreage and the industry continues investing in trade development, the current rebound can be sustained.

Conclusion

U.S. wheat exports are poised to reach their highest level in five years, a reflection of competitive pricing, strong demand for hard red winter wheat and tightening global supplies. Farmers stand to benefit from this export-driven demand, but the longer-term outlook will depend on stabilizing acreage and capturing new markets.

U.S. wheat remains a cornerstone of the global food supply and stands to benefit from policy, trade and commitment from farmers. This year's rebound could serve as the foundation for long-term strength for one of America's most historic and globally respected crops.