Bullish Cattle Report Does Not Indicate Herd Expansion

Bernt Nelson

Economist

Key Takeaways

- USDA’s Cattle on Feed report indicates continued tight feeder cattle supplies. USDA estimates cattle on feed on Nov. 2 were 11.7 million head, down 2%, or 260,000 head from 2024. Approximately 2.04 million head of cattle were placed into feedlots, down 227,000 head, or 10%, from 2024.

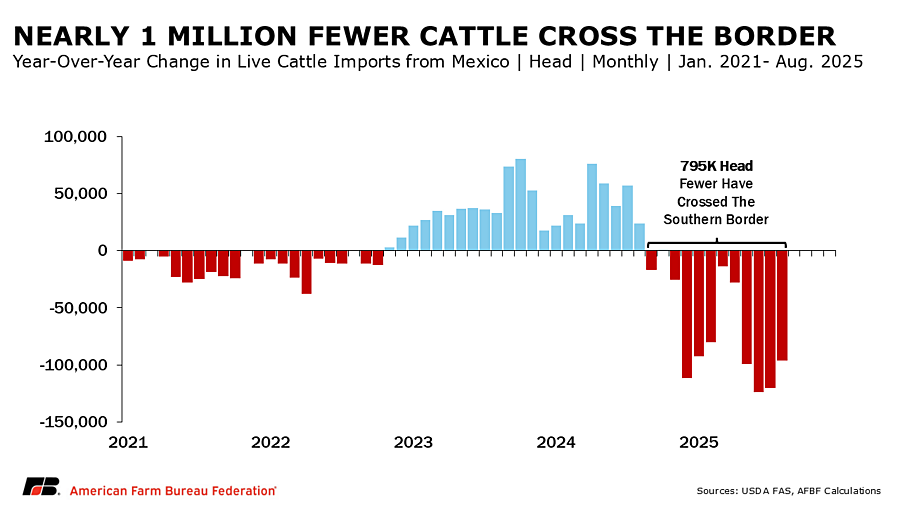

- Halted imports from Mexico are contributing to the decline in cattle on feed in U.S. The U.S. has banned the import of live cattle from Mexico to protect the domestic herd from New World screwworm. This has resulted in 795,000 fewer head of cattle imported from Mexico between November 2024 and August 2025 compared to the same period between 2023 and 2024.

- Packing plant closures, among other factors, have led to lower cattle prices and massive market volatility. Falling cattle prices are coming at a time when cattle farmers are typically making decisions about whether to hold back heifers for breeding or place them on feed. Retaining heifers for breeding could lead to herd expansion in 2028, but with input costs at near-record levels and prices still 25% higher than a year ago, there is a lot of incentive for farmers to market cattle rather than hold them back for breeding.

USDA released its first Cattle on Feed report (COF) since September, on Nov. 21. On the same day, Tyson Foods also announced the closure of a beef processing facility in Lexington, Nebraska, and decreased capacity in its Amarillo, Texas, plant. These reductions in capacity will have longer-term market impacts. This Market Intel evaluates the COF report, decreased processing plant capacity and other key pieces of the supply chain that could have lasting impacts on cattle markets.

Cattle On Feed

According to USDA’s COF report, there were 11.7 million cattle on feed in the United States on Nov. 1. This is down about 2% from 2024 and the lowest number of cattle on feed for the month of November since 2018. The report also estimates that 2.04 million head of cattle were placed into feedlots, down 227,000 head, or about 10%, from last year. This is the lowest number of cattle placed on feed for the month of October in report history. Marketings of fed cattle were 1.7 million head, about 8% below last year and the lowest for November in a decade.

Lower cattle placed on feed and marketings of fed cattle are a reflection of tighter supplies of feeder cattle, a result of both the border closure and where we are in the cattle cycle.

- Cattle on feed in Texas fell nearly 9% from 2.88 million to 2.63 million head.

- Cattle on feed in Nebraska increased 3% from last month and 2.3% from last year to 2.64 million head, a new record for the state in November -- overtaking Texas as the state with the most cattle on feed for November 2025.

- Cattle on feed in Kansas totaled 2.46 million head, up 50,000 head, or 2%, from 2.41 million both last month and last year, putting the state in third place behind Texas for total number of cattle on feed.

- Colorado took fourth place in the report with about 920,000 cattle on feed in November, even with last month, but down about 140,000 head, or 13%, from last year.

- Iowa came in fifth place with 700,000 head of cattle on feed in November, up 10,000 head from last month and up 30,000 head, or 4%, from last year. This marks the highest inventory of cattle on feed for Iowa in November since 2018.

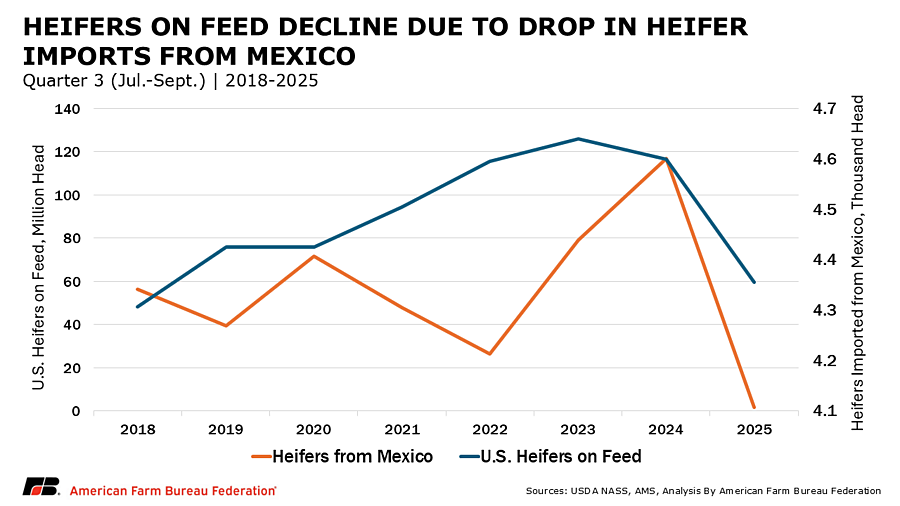

The most important number when considering efforts to rebuild the herd is the number of heifers on feed. According to the COF report, the number of steers on feed was up 1% from last year at 7.63 million while the number of heifers on feed was 4.36 million head, down 245,000 head, or 5%, from last year -- and the fewest heifers on feed in November since 2018.

Typically, the decline in heifers on feed compared to steers on feed could be a sign that herd rebuilding has begun because it would indicate farmers have begun keeping heifers for breeding rather than placing them on feed. However, this decline in heifers on feed is more likely connected to fewer heifers being imported from Mexico due to the border closure caused by New World screwworm.

Impacts of New World Screwworm

USDA closed the U.S.-Mexico border to imports of cattle, bison and equines in Nov. 2024 as a precautionary measure against the spread of New World screwworm. The border was re-opened in February 2025 and closed again in May as detections moved northward in Mexico. An additional phased reopening of the border was halted in July, and the border has remained closed to these animals since then.

According to the most recent data from USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service, imports of cattle from Mexico from November 2024 through August 2025 were about 795,000 head behind the same time period in 2023 through 2024. Most of the cattle coming to the U.S. from Mexico are feeder cattle to be placed on feed. The decline in cattle imports from Mexico is a large contributing factor for USDA’s reported sharp drop in cattle placed in feedlots in Texas.

To prevent the spread of brucellosis, heifers imported from Mexico are spayed and placed on feed instead of being used for breeding. While the number of heifers on feed on Oct. 1, 2025, was down 5% compared to October 2024 (USDA reports data for heifers on feed quarterly), the 2024 report includes about 116,000 spayed heifers imported from Mexico compared to just 1,672 spayed heifers on Oct. 1, 2025. This is approximately 86% lower than the same period last year. When the drop in heifers from Mexico is considered, the COF report does not indicate strong heifer retention from the domestic herd that would lead to meaningful expansion in the cattle inventory. In a normal environment, this would be fundamentally bullish.

Packing Plant Closures

Tyson Foods announced on Nov. 21 that they will close their beef processing plant in Lexington, Nebraska, in January 2026. This plant has a capacity to process about 5,000 head per day, or about 5% of total U.S. slaughter capacity. Tyson also plans to reduce its Amarillo, Texas, plant to a single, full-capacity shift that is expected to reduce the daily harvest from 5,500 head to 2,700 to 2,800 head. Feeder cattle futures markets opened limit down (the maximum price change allowed for a commodity futures contract in a single trading day) on the Monday following the announcement. Tyson states the reason for these capacity changes is to “optimize production volumes across its network to meet customer demand.”

U.S. beef packers have been operating well below total processing capacity since 2022 due to declining cattle supplies. One study estimates that the annual slaughter in 2025 will be about 30.5 million head, or 13% below the total annual packing capacity of 34.96 million head. This led many industry experts to predict some plant closures during 2025 and 2026.

Market Impacts

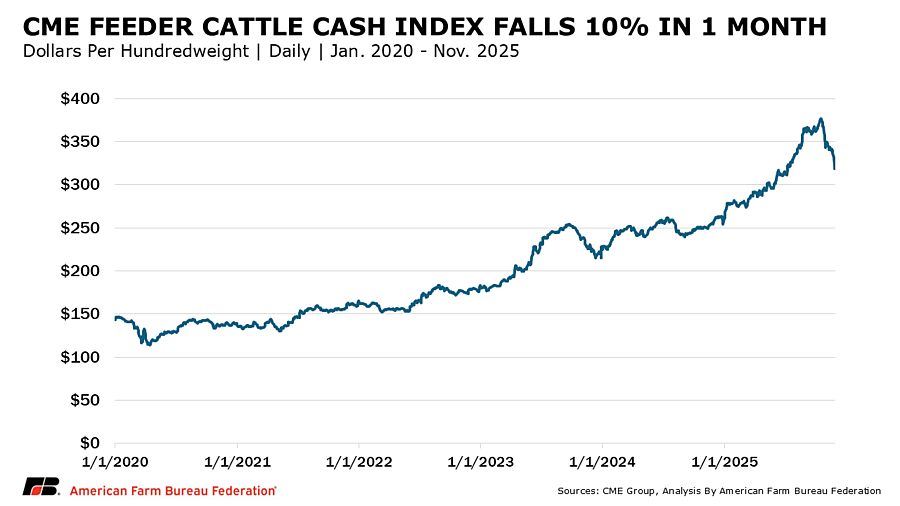

Cattle prices have recently experienced massive volatility. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s daily Feeder Cattle Cash Settlement Index was $318.76/cwt on Nov. 27. This is the lowest price since July 2025 and follows the index reaching a record high of $376.51/cwt on Oct. 16.

Falling cattle prices are coming at a time when cattle farmers are typically making decisions about whether to hold back heifers for breeding or place them on feed. Retaining heifers for breeding could lead to herd expansion in 2028, but with input costs at near-record levels and prices still 25% higher than a year ago, there is a lot of incentive for farmers to market cattle rather than hold them back for breeding. Fundamentally, this means cattle supplies will likely remain tight through 2026, which will delay expansion even further.

Conclusions

USDA’s latest Cattle on Feed report reflecting impacts of the ongoing suspension of cattle imports from Mexico, combined with recent processing capacity reductions, underscores the fundamental pressures shaping U.S. cattle markets. Feeder cattle supplies are historically low. Placements and heifer numbers are declining not because of domestic herd rebuilding, but due to the sharp drop in Mexican cattle imports following the New World screwworm-related border closure. At the same time, packers continue to face underutilized capacity, resulting in substantial operational changes that will impact the supply chain for years to come.

These supply constraints, along with shifting processing capacity, have led to higher market volatility and sharply lower feeder cattle prices at a time when farmers are making key decisions about whether to market cattle or keep them for breeding. With near-record input costs and uncertain profit margins, lower prices could lead many farmers to market cattle rather than hold back replacements, limiting the potential for near-term herd rebuilding. As a result, cattle supplies are likely to remain tight well into 2026 and delay meaningful expansion in the U.S. cattle herd until at least 2028.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL