Carving Out a Living: Celebrating America’s Pumpkin Market

TOPICS

Specialty Crops

photo credit: Kentucky Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Every autumn, pumpkins take center stage in America, adorning porches as jack-o’-lanterns, starring in pies and lattes and fueling a seasonal economy. What began as an old Irish tale of “Jack of the Lantern” (originally carved from turnips) has grown into a multi-million-dollar U.S. industry. Native to North America, pumpkins are truly an all-American crop, one of the continent’s oldest cultivated plants and a symbol of fall. In 2021, Americans spent over $10 billion on Halloween festivities, and nearly 94 million people planned to carve pumpkins, a testament to the cultural and economic weight of this (typically) bright orange crop. This Market Intel explores U.S. pumpkin production and a few of the challenges their dedicated farmers face.

Pumpkin Production and Use Dynamics

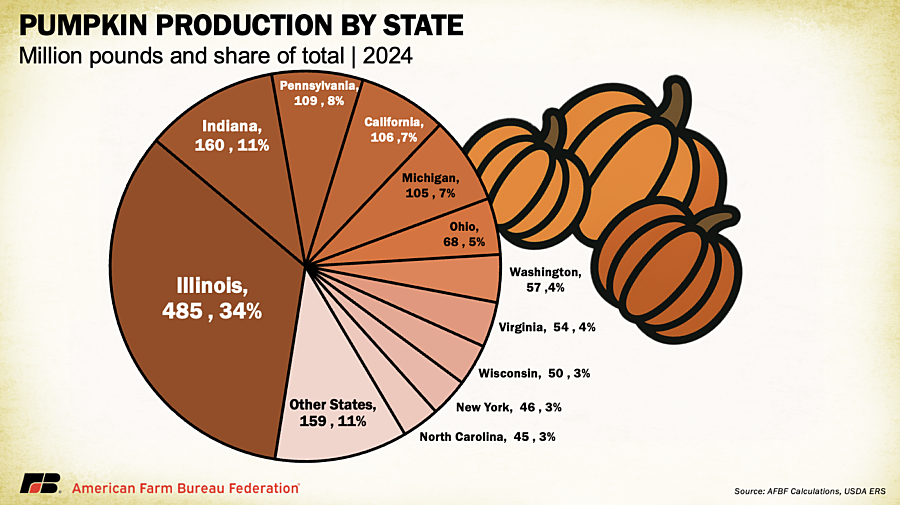

Pumpkins are grown across the country on more than 68,000 acres, producing roughly 1.4 billion pounds in 2024. A handful of states dominate: Illinois, Indiana, Pennsylvania, California and Michigan together account for about 66% of all pumpkin output. Illinois alone harvested about 15,400 acres and produced 485 million pounds, more than the other four top states combined.

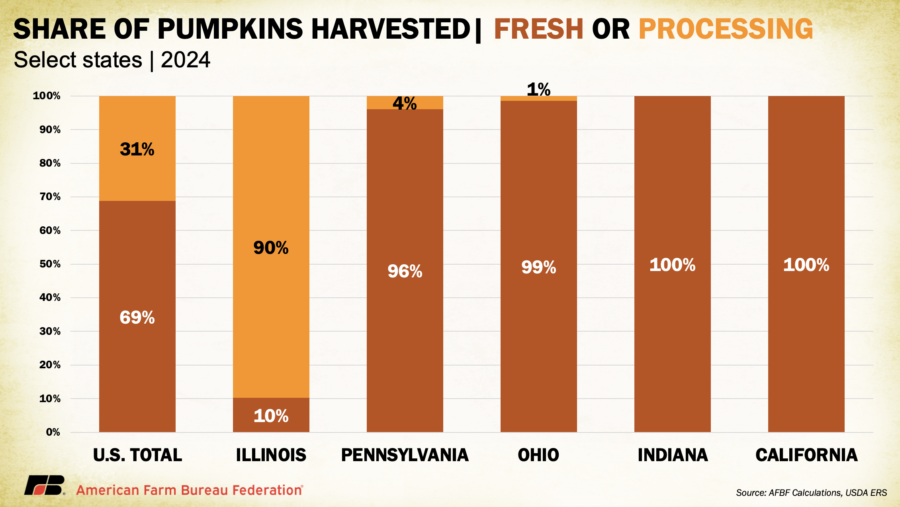

Illinois’ edge lies in processing pumpkins with 90% of its crop going to pie filling and canned products. Libby’s, the major canned pumpkin processor, sources nearly all its pumpkins from Illinois. Elsewhere, growers focus on fresh ornamental pumpkins for carving or decoration. The U.S. now grows an eclectic mix, from classic Howden jack-o’-lanterns to white “ghost” pumpkins and warty heirlooms, as consumers crave distinctive fall displays. Yields vary widely with Illinois’ processing fields averaging 31,500 pounds per acre in 2024, while states like Pennsylvania averaged about 16,000 pounds per acre.

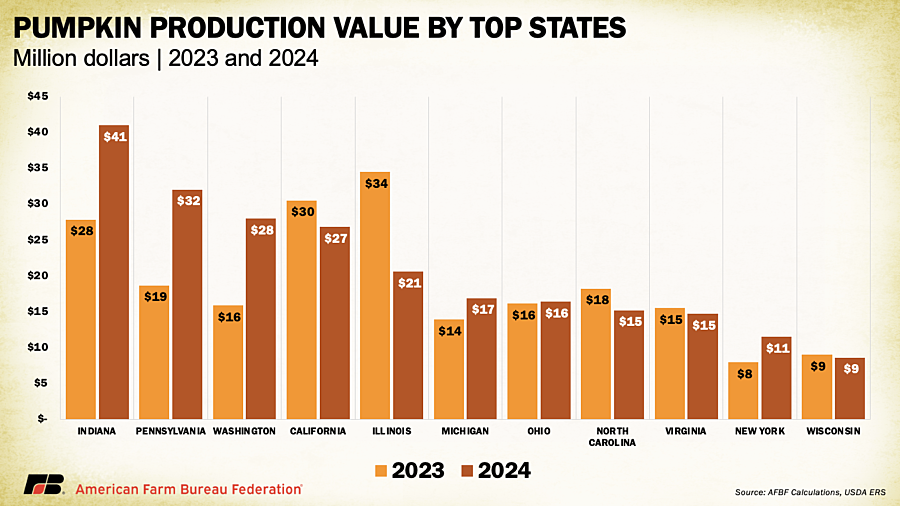

In total, U.S. pumpkin farmers produced over $274 million in value in 2024. Illinois led in volume but earned just $21 million because of lower processing prices, compared with $40 million in Indiana, $32 million in Pennsylvania, and $28 million in Washington. Prices range dramatically, from Illinois’s $50 per 1,000 pounds (about 5 cents per pound) for processing pumpkins to Washington’s $324 per 1,000 pounds (about 32 cents per pound) for fresh pumpkins. Retail prices reflect the same trend. In October 2024, a large carving pumpkin averaged $6.21, wholesale bins sold around $157 for carving pumpkins and $212 for smaller pie pumpkins, while rare heirloom varieties reached $350 per bin.

On the international front, the U.S. exported $26.3 million in pumpkins in 2024, mainly to Canada ($21.8 million) and Mexico ($3.3 million), and imported $21.7 million, primarily from Canada, Costa Rica and Panama. In 2024, the U.S. also exported $3.8 million in pumpkin seeds with $2.2 million going to Canada, $410,000 to Germany and $314,000 to the United Kingdom.

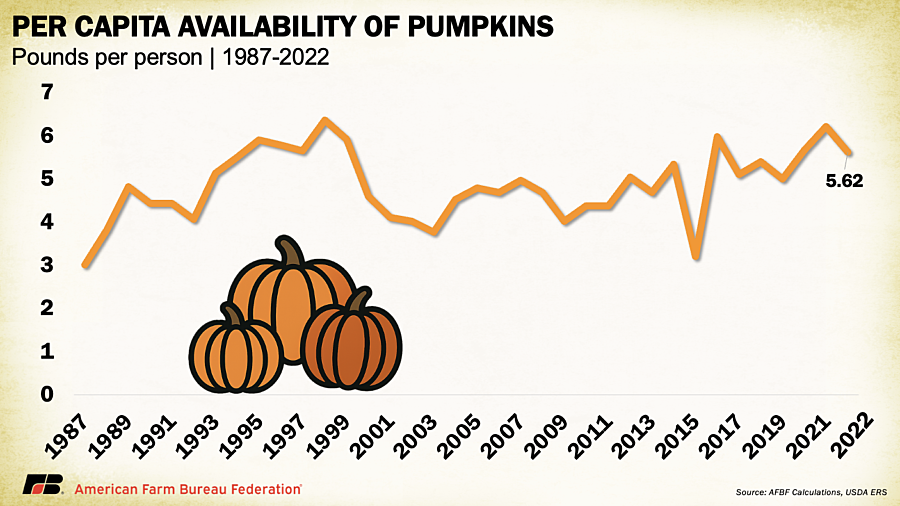

Pumpkins are planted in late spring and harvested just before fall, with roughly 80% of production and use occurring during autumn holidays. Per-capita consumption/use has climbed to 5–6 pounds per year, up from 4 pounds in the early 2000s.

Challenges for Pumpkin Farmers

Pumpkins may look whimsical, but the farmers who grow them face the same pressures confronting specialty crop farmers broadly: steep expenses for labor, inputs and infrastructure combined with few insurance or risk-management options. Weather is often the biggest wildcard: too much heat and the crop ripens too early in August and too much rain and it rots before Halloween. Drought, floods and early frosts all have disrupted harvests. The “Great Pumpkin Flood” in 1786 reportedly sent entire patches floating down the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania.

Insects, diseases and wildlife add to the trouble. Vine borers, cucumber beetles and powdery mildews can devastate fields, while deer happily graze on young plants. Many growers invest in hybrid seeds bred for disease resistance, even though they cost three to eight times more than standard varieties. Bees are essential, too: because pumpkins have separate male and female flowers, growers sometimes rent hives at $45 to $200 per hive to ensure adequate pollination.

Harvest brings its own challenges. Ornamental pumpkins are hand-picked and handled carefully to preserve the stems that shoppers prize, creating intense seasonal labor demand. In Illinois’s processing fields, mechanized harvesters reduce labor needs but require costly equipment. Either way, pumpkins are bulky and perishable and getting them out of the field, onto trucks and into stores before they soften is a race against time.

Risk Management

Traditional crop insurance hasn’t always fit specialty crops like pumpkins, but there is progress. In Illinois, USDA’s Risk Management Agency recently made its Processing Pumpkin coverage permanent. Beginning with the 2025 crop year, farmers can now insure yields up to 85% of their historical average and even get coverage in previously ineligible counties through special agreements. Only pumpkins grown under processor contracts qualify, but those contracts themselves serve as price protection.

For most pumpkin growers, though, especially those selling directly to consumers, formal insurance options remain limited. Many turn instead to USDA’s Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP), which provides basic yield and revenue coverage for crops that aren’t eligible for federal crop insurance. Under NAP’s basic 50/55 coverage, indemnities only kick in after losses exceed 50% of the approved yield, and payments are limited to 55% of the average market price, although producers may elect buy-up coverage (50–65% of yield at 100% of market price) if they pay higher premiums. These thresholds, caps, and costs mean NAP is often only a partial safety net, not a full substitute for federal crop insurance.

In 2024, about 7,100 acres of pumpkins worth $5.6 million were insured nationwide. Still, coverage remains limited. In 2020, USDA’s Economic Research Service estimated 56% of pumpkin acreage was uninsured, 31% insured under NAP and 13% under federal crop insurance. For many growers, especially those marketing directly to consumers, risk management relies more on diversification, staggered planting and smart timing than on existing program offerings.

Bottom Line

Whether carved, canned or crafted into a latte (even if that “pumpkin” flavor is mostly spice and spirit), pumpkins embody the creativity and resilience of American farmers. Their short harvest window and high production costs mirror the broader policy challenges facing specialty crops, from limited insurance options to seasonal labor constraints. Each jack-o’-lantern, then, is a reminder that smart farm policy helps keep autumn’s brightest symbol glowing bright.