Specialty Crops: Mounting Cost Pressure, Limited Risk Protection

TOPICS

Specialty Crops

Daniel Munch

Economist

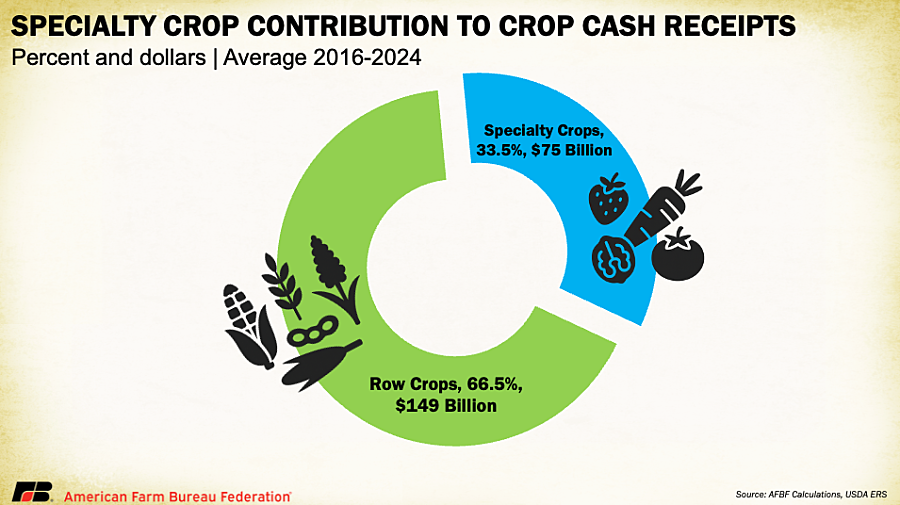

For specialty crop farmers, 2025 has offered little relief from mounting financial pressures. Markets that once promised stable margins are now defined by volatility, with production expenses outpacing price gains and exports at risk under global trade uncertainties. Despite contributing over $75 billion in farm-gate value — over a third of all U.S. crop sales — specialty crop producers have fewer risk-management and safety-net options to help weather these challenges. The result is a widening gap between cost and revenue that threatens profitability across much of the farm economy.

Specialty crops encompass more than 350 commodities, from almonds and apples to lettuce and lemons, and account for roughly one-fifth of U.S. agricultural cash receipts across 220,000 farms. Yet the diversity that defines the sector also amplifies its vulnerability. Each crop relies on distinct production systems, marketing channels and labor demands, making it difficult to design one-size-fits-all safety nets or risk-management tools.

These structural realities compound the challenges growers face from unique weather and pest pressures, evolving regulatory requirements and the often-perishable nature of their products. Many specialty crops are sold in markets with few buyers and limited price transparency, leaving producers unable to hedge against downturns or forecast cash flow with confidence. Buyers of specialty crops often look for the lowest price in the global marketplace to ensure consumers have access to cost-effective produce, putting high-cost American production at a disadvantage. Growing consumer expectations for fresh produce in every season have led to more fruits, vegetables and nuts being imported, putting added pressure on U.S. specialty crop farmers. The absence of robust insurance or futures markets further amplifies exposure, while complex marketing systems often delay disaster aid for years after losses occur. Labor dependency adds another layer of risk (especially for fruit, vegetable and nursery operations reliant on the H-2A program) where visa uncertainty, regulatory burdens and rising wages can quickly erode margins.

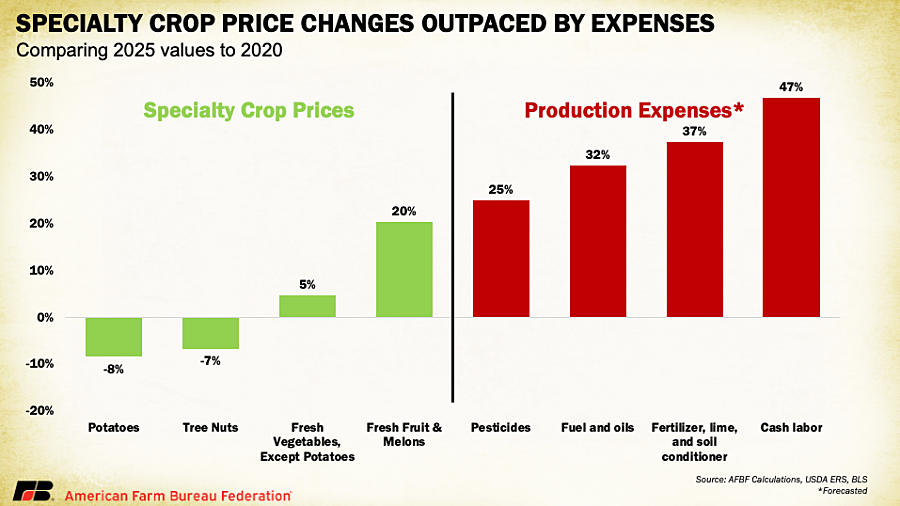

Even in sectors where prices have climbed, those gains have been far outpaced by production expenses, leaving limited opportunities to break even. Between 2020 and 2025, producer price indices show that selling prices for potatoes and tree nuts declined by 8% and 7%, respectively, while fresh vegetables (excluding potatoes) rose just 5% and fresh fruit and melons increased about 20%. Over the same period, growers paid 25% more for pesticides, 31% more for fuel, 37% more for fertilizer and nearly 50% more for labor. These trends mirror the broader input cost pressures facing row crop producers, who are enduring another year of sustained losses.

These cost pressures are magnified by the structural realities of specialty crop production. Unlike most field crops, many fruit, vegetable and nut operations cannot rely on broad-scale mechanization, requiring either intensive manual labor or costly investments in specialized technology. Custom equipment, unique trellising systems and crop-specific inputs such as precision irrigation or pest control add further expense.

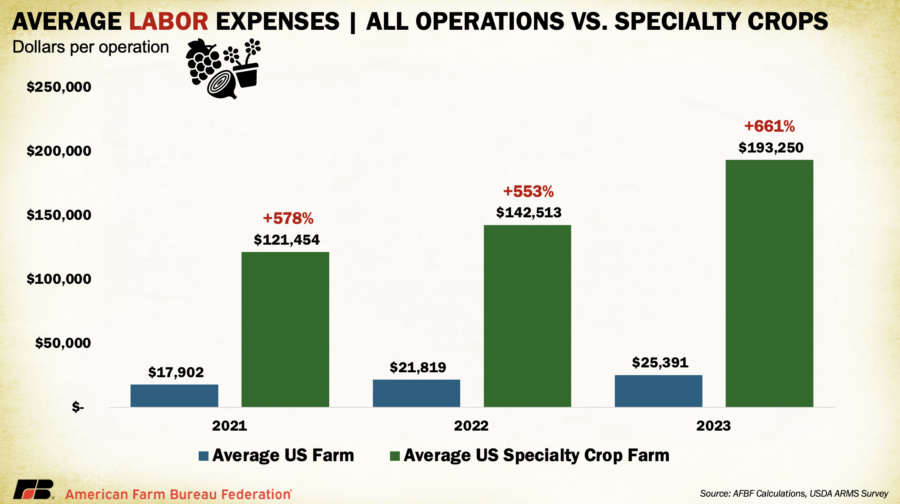

According to USDA’s Agricultural Resource Management Surveys, specialty crop farms averaged more than $466,000 per farm in cash expenses in 2023, up 47% from 2021 and 160% higher than the average farm operation. Labor alone, which accounts for nearly 40% of total production costs, averaged $193,250 per farm, up 60% from 2021 and over six times higher than the national average. With input inflation persisting and disruptions to labor conditions in 2025, these structural costs continue to weigh heavily on profitability across the sector.

Specialty Crops’ Multitude of Markets and Individual Challenges

Each specialty crop has its own supply and demand conditions and thus a different profitability story. Discussing a few commonly grown U.S. specialty crops illustrates the depth of some of these challenges at a more granular level.

Almonds remain the nation’s highest-value tree nut crop, generating about $5.6 billion in 2024, but the industry has been under financial stress. From 2019 to 2023, the average almond price declined to $1.81 per pound, down from $3.05 per pound during 2014–2018. Meanwhile, cost and return studies from the University of California show operating expenses increasing roughly 40% between 2019 and 2024, while gross returns fell 36%, pushing net returns into negative territory. In the Sacramento Valley, net returns above total costs shifted from a modest $205 per acre gain in 2019 to a $4,280 per acre loss by 2024, leaving many operations unable to service debt or absorb high irrigation and input costs. Over this period, an estimated 66,000 acres of almond orchards, about 5% of total growing area, were removed, as prolonged negative returns forced growers to idle or tear out orchards rather than continue producing at a loss.

Walnut growers have faced similarly steep losses. According to the last UC Davis cost-and-return study for the Sacramento Valley, total operating costs reached about $2,900 per acre, with total costs (including overhead and capital recovery) near $8,000 per acre. At the study’s assumed price of 50 cents per pound, growers received roughly $3,000 per acre in revenue, resulting in losses exceeding $5,000 per acre once full costs were considered.

In the fruit sector, profitability challenges also persist. The U.S. apple industry faces declining export demand without increased domestic consumption, leaving prices often falling beneath packing, storage and input costs, even as innovation has boosted supply. The latest Washington State University enterprise budgets for Honeycrisp apples show net losses of roughly $12,000 per acre once orchards reach maturity, with total returns around $38,000 per acre against production costs exceeding $50,000. This underscores how even high-value varieties remain financially unsustainable for many family-run orchards struggling to service debt or reinvest in new plantings.

Blueberry producers are also caught in a razor-thin margin environment. Michigan State University’s 2024 cost study estimates full-production expenses exceeding $10,400 per acre, with “management income” (the residual after covering all cash and fixed costs) at just $240 per acre. In practical terms, that means nearly all revenue is consumed by production expenses, leaving almost nothing to compensate the grower’s personal labor or risk.

Strawberry growers face some of the highest per-acre costs in agriculture, driven by intensive hand-planting, harvesting and replanting requirements that allow little mechanization. UC Davis studies estimate production expenses near $113,000 per acre (an 18% increase since 2021) with projected losses exceeding $14,000 per acre at typical yields. Break-even prices near $12–$14 per tray exceed what markets have paid for most of 2024 and 2025, demonstrating how escalating labor expenses and low consumer prices collide and put farmers in the red.

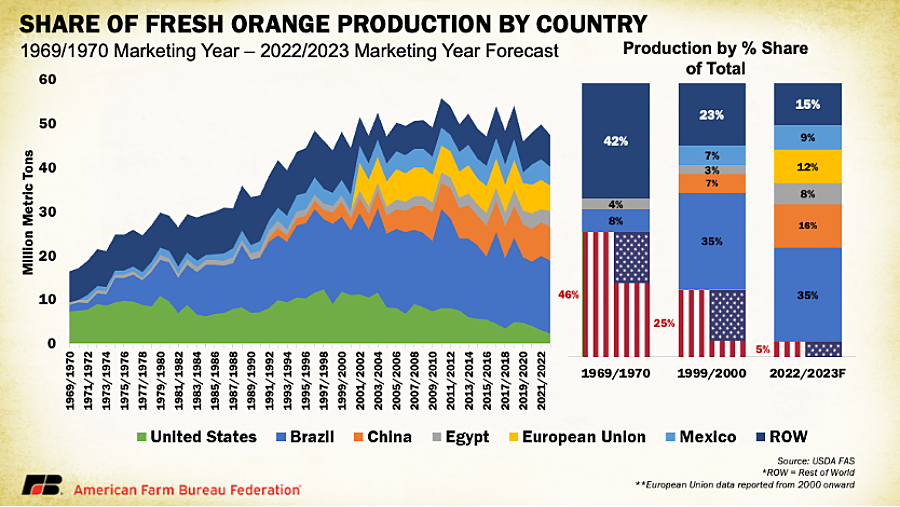

Citrus growers have endured one of the steepest cost escalations in specialty agriculture. The cost of farming navel oranges in California rose from $1,555 per acre in 2005 to $4,215 by 2025, while regional regulatory compliance costs alone jumped from $67 to $447 per acre between 2012 and 2018. Even after Canadian tariffs on U.S. citrus were lifted in early 2025, years of rising imports, persistent disease pressures and stagnant prices have left growers with razor-thin returns. Declines in U.S. production, especially Florida, from these pressures have diminished the country’s longtime role as a leader in global market share. In 1970, for instance, the U.S. produced nearly half of the world’s oranges. This number dropped to 25% by 2000 and is expected to be just 5% for 2023.

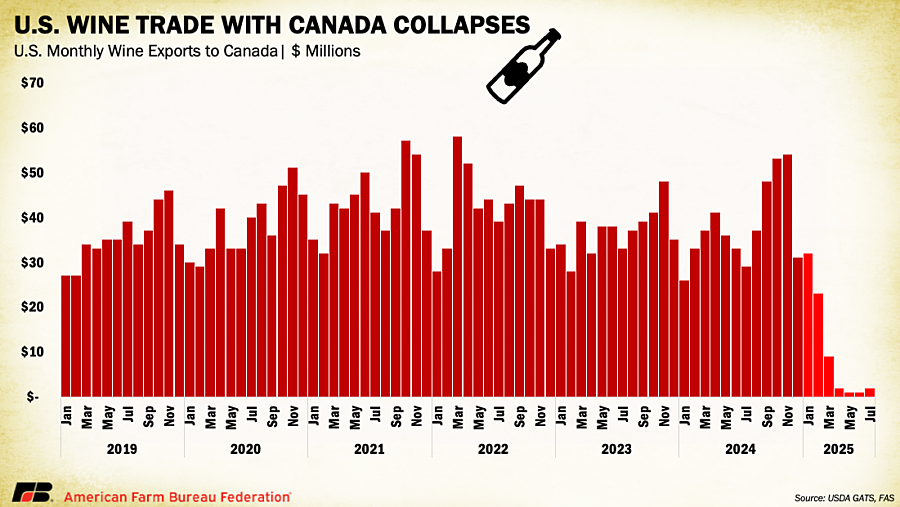

In the wine industry, weak demand continues to weigh heavily on grape prices. U.S. exports to Canada (a key market) have collapsed. Since 2019, Canada regularly imported $20 million to $60 million in U.S. wine each month; so far this year, those shipments have fallen to nearly zero. Silicon Valley Bank’s State of the U.S. Wine Industry 2025 projects that up to 50,000 acres of vineyards may need to be removed to restore market balance.

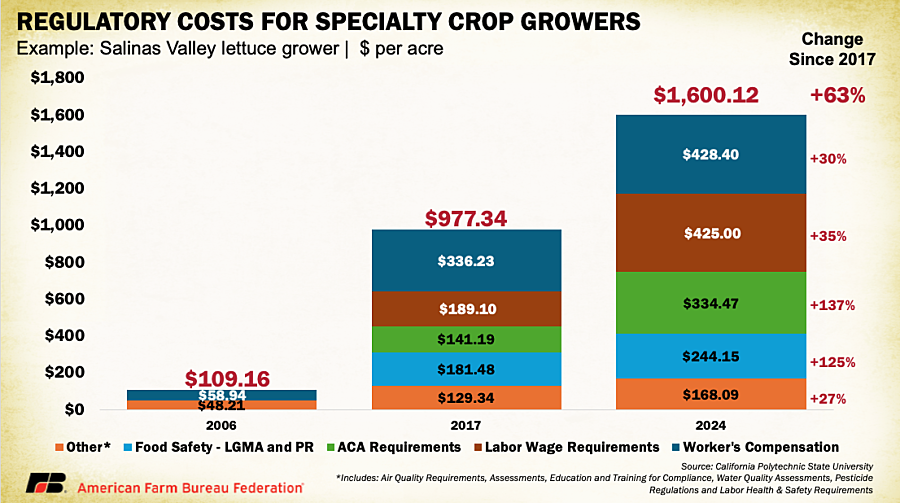

Vegetable growers have not been spared from the mounting cost pressures facing specialty crop producers. Romaine lettuce prices have dropped to $14.55 per carton in 2025, almost half of 2024 levels, while per-acre production costs hover around $17,000,about $17 to $20 per carton at typical yields of 850 to 1,000 cartons per acre. Compliance costs tied to food safety, labor and water quality rules have surged fifteen fold since 2006, rising from $109 per acre to over $1,600 per acre on Salinas Valley lettuce operations. According to Cal Poly’s long-term case study, these expenses (driven by evolving food-safety mandates, groundwater monitoring and new labor laws) now make up over 12% of total production costs, compared to barely 1% two decades ago. Similar pressures extend across the country. In Florida, tomato producers face production costs near $37,000 per hectare (roughly $15,000 per acre) but earn only about $33,400 in revenue, leaving an implied loss of roughly $3,600 per hectare. Labor makes up 30%–40% of total expenses, and growers capture only about one-third of the retail price.

Potatoes aren’t immune either. In Idaho, the nation’s top producer, growers averaged about 43,000 pounds per acre in 2024, with marketing year prices near $9.63 per cwt, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. Monthly grower prices for fresh potatoes ranged from $10.20 to $10.60 per cwt in early 2024, generating roughly $4,000 to $4,500 in gross revenue per acre before costs. Typical production budgets across the Pacific Northwest place full costs at $5,000 to $7,000 per acre, leaving little cushion for open-market (uncontracted) potatoes that lack pre-season pricing agreements and are exposed to post-harvest price swings. Analysts describe those uncontracted acres as unprofitable in 2025, underscoring how even staple crops face mounting financial strain.

With freight and energy costs rebounding and diesel prices forecast to rise again in 2025, growers are struggling to maintain cash flow in an environment where regulations alone can consume more than one-tenth of total production costs. The result is a produce sector operating on margins often too thin to absorb new shocks — whether regulatory, market or environmental.

Limited Risk Management and Safety Net Tools for Specialty Crops

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) remains the foundation of U.S. farm risk management and provides vital stability for producers across commodities. For specialty crop growers, however, structural gaps persist. While insured liabilities for fruits, vegetables and nuts have expanded from about $1 billion in 1990 to more than $25 billion in 2022, over 43% of fruit and nut acreage and 47% of vegetable and melon acreage remain uncovered by either FCIP or the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP).

Unlike major field crops, specialty commodities do not qualify for Title I programs such as Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) or Price Loss Coverage (PLC), with the limited exceptions of dry beans, lentils and chickpeas. As a result, the enhancements to ARC and PLC under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), including higher reference prices and expanded coverage triggers, do not apply to most specialty growers, leaving them outside the reach of the farm bill’s core safety net improvements.

Part of the challenge lies in the diversity of specialty crops themselves. More than 350 commodities are grown using region-specific practices and marketing arrangements that make it difficult to design uniform insurance products. Where FCIP policies exist, coverage levels are often based on yield rather than revenue, offering little protection against market-driven price swings. For crops without FCIP options, NAP provides only partial coverage, with payments triggering only after losses exceed 50%, and indemnities are limited to 55% of average market price unless producers purchase additional “buy-up” coverage. Even then, high premiums and administrative caps can discourage participation.

When large-scale disasters strike, specialty growers often turn to ad hoc relief programs, but these have also revealed structural shortcomings. Under USDA’s Emergency Relief Program (ERP) and Supplemental Disaster Relief Program (SDRP), most payments were distributed through “Phase 1,” which used existing RMA crop insurance data to automatically pre-fill applications for covered commodities. Specialty crops, by contrast, were largely pushed into “Phase 2,” where payments must be manually verified using tax and production records because no standardized yield or price data exist. As a result, specialty crop producers have received only 8% of SDRP payments so far, despite representing nearly 20% of documented crop losses in 2024 (~$4 billion in losses). Many growers with losses dating back to early 2023 are still waiting for an established framework to calculate or be issued compensation under SDRP. These delays illustrate a broader equity gap in disaster assistance: without standardized data, specialty crops are routinely placed at the end of the payment line.

Important progress has been made recently. OBBBA increased premium support and broadened access to the Supplemental Coverage Option, but it stopped short of implementing the specialty-specific reforms envisioned in the Farm, Food and National Security Act (FFNSA). FFNSA would have created a Specialty Crop Advisory Committee, directed RMA to prioritize policy development for wine grapes, mushrooms and pulse crops, and encouraged research into mechanization and automation to reduce labor risk. Advancing these types of reforms, without diminishing the strength of existing crop insurance programs, remains key to ensuring a more balanced and responsive safety net.

Conclusion

Specialty crops are a cornerstone of U.S. agriculture, supplying fresh, nutritious food to families worldwide and supporting hundreds of thousands of farm families. Yet in 2025, profitability for many of these growers is increasingly at risk. Rising production costs, trade uncertainty and limited safety net coverage have eroded margins, even in high-value markets, with few tools available to manage risk.

A more responsive safety net will be essential to sustaining the diversity and resilience of U.S. agriculture. Timely disaster assistance, stronger data collection and integration, and expanded risk management options can help ensure the nation’s fruit, vegetable, nut and horticulture producers remain competitive in an era of high costs and heightened risk.