Market Issues to Track for 2022

TOPICS

Supply Chain

photo credit: Getty Images

Roger Cryan

Former AFBF Chief Economist

Market Issues to Track for 2022

May you live in interesting times.

- Chinese curse

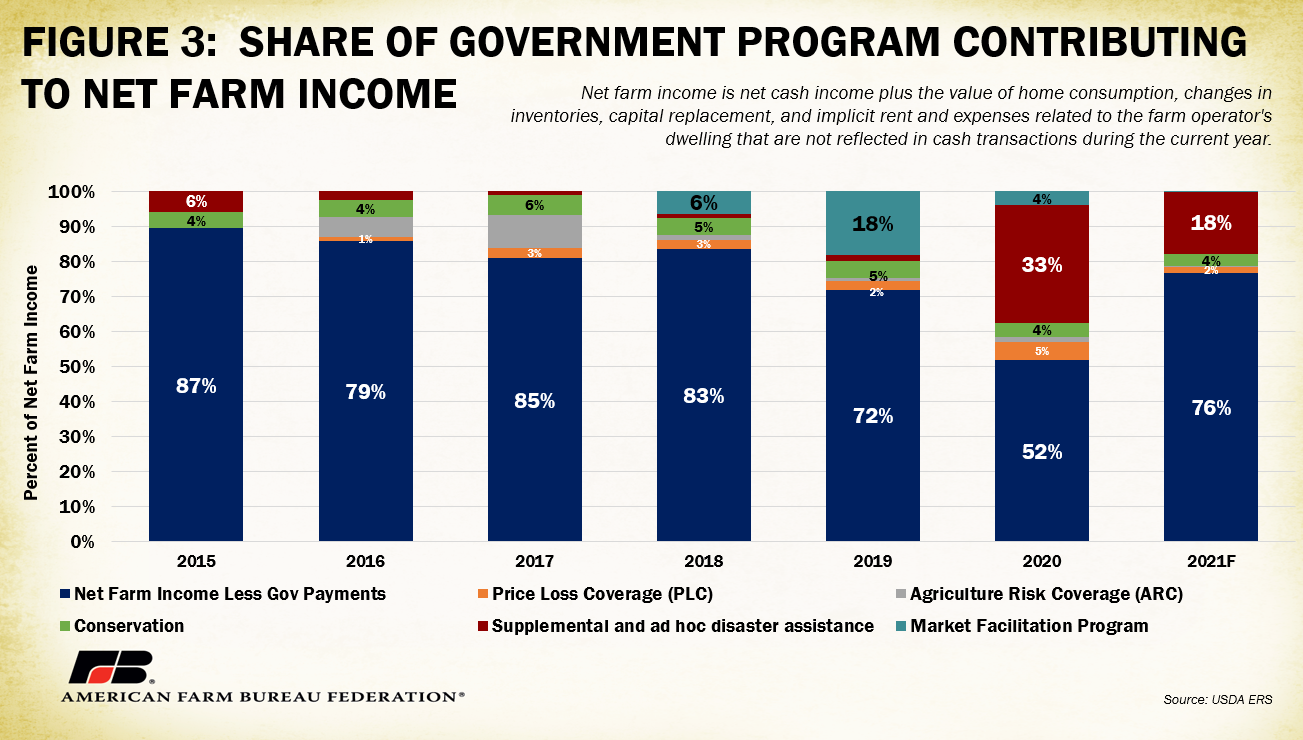

Rising prices, strong worldwide demand and more than $27.2 billion in government payments drove net farm income in the U.S. to $117 billion in 2021, its highest level in eight years. The outlook for 2022 depends on a range of market issues, including those outlined below. Remember, though, we continue to live in “interesting times,” so any projections should be viewed with caution.

The pandemic continues as new variants emerge, constantly redefining the crisis and shifting the shape of supply and demand and its impact on the farm economy. Whether the tentative reopening of the service economy continues in 2022 will depend on the course of the pandemic.

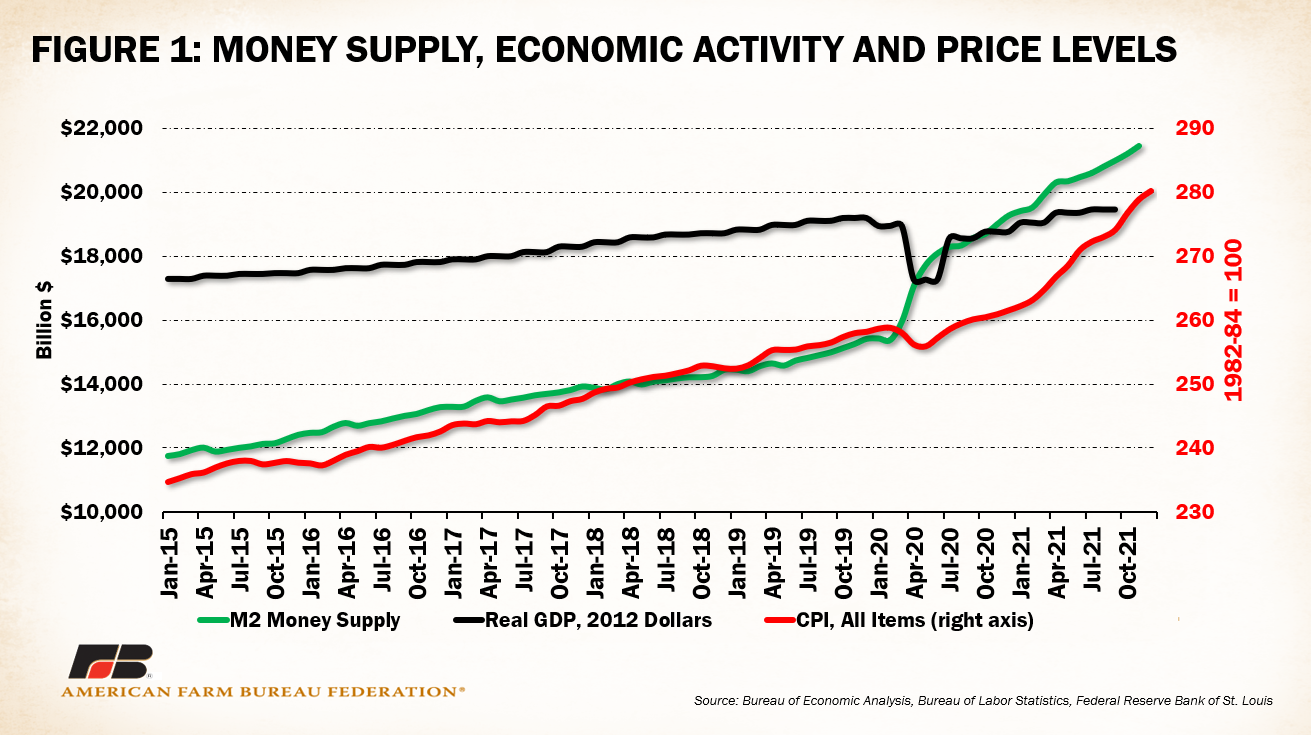

In response to the pandemic and its economic fallout, the Federal Reserve Bank undertook unprecedented bond buying and lending to banks to support the economy directly and to support trillions of dollars of extra government spending. This massive expansion of the money supply has led, as it had to, to the highest rates of inflation in nearly 40 years. The 1970s and 80s should remind us how destructive inflation – and its eventual correction – can be, if it is not nipped in the bud.

U.S. agricultural trade hit new records in fiscal year 2021. Whether there are new records in fiscal year 2022 will depend somewhat on market forces, but more (perhaps) on geopolitics.

The end of 2021 means the end of Chinese purchase commitments for U.S. farm products under the so-called Phase One Agreement, but benefits and impediments remain, including a list of resolved structural barriers to U.S.-China trade, as well as higher tariffs. Whether the U.S.’ elevated agricultural trade with China continues beyond their Phase One commitments remains to be seen.

With no biotech approvals since 2018, a rejection in 2021 and a presidential decree that bans imports of biotech corn by 2024, Mexico’s increasingly uncertain policy toward biotechnology is another U.S. export geopolitical wildcard in 2022.

Finally, imported agricultural inputs have become much more expensive, as China has limited fertilizer exports to support its agriculture sector and sanctions against Belarus have practically cut off a major world source of potash.

Closer to home, the unemployment rate, at 4.2%, is down considerably from the April 2020 high of 14.8%, but remains above pre-pandemic levels. A rebounding economy has resulted in an increased number of job openings, but also an explosion in business applications. Workers, changed by the COVID experience, are demanding – and holding out for – more; as a result, the entire economy is facing the sort of labor difficulties farmers have long endured, and that’s unlikely to change in 2022.

No part of the transportation sector has been spared supply-chain disruptions, with higher rates and shipping delays often hitting farmers and ranchers particularly hard. A continuing shortage of truck drivers has driven freight rates back above their pre-pandemic highs. Rail rates for bulk farm commodities have, in part, been driven up by limited rail terminal capacity.

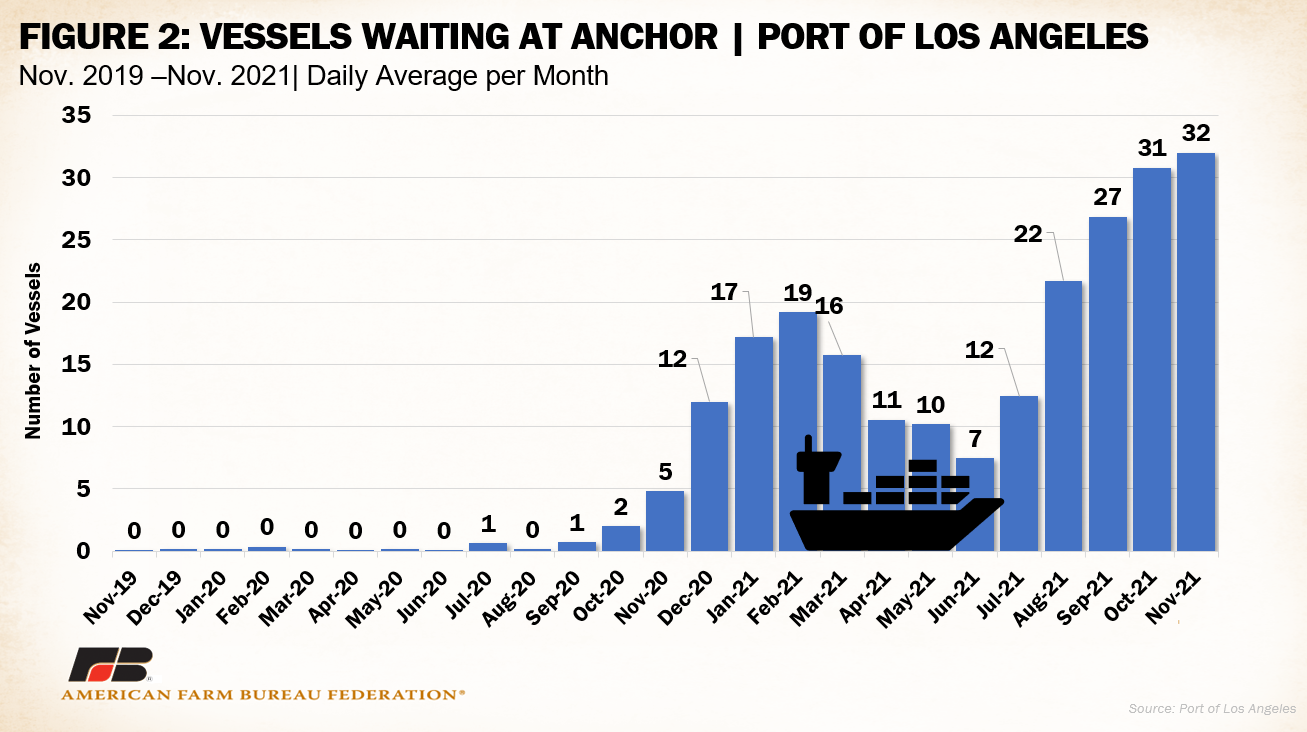

Agricultural exports, though at record levels, were held back from even greater heights by a shortage of containers, leading many foreign shippers to retrieve empty containers rather than allowing them to collect American loads for export. Imports of critical agricultural inputs were also constrained by maxed-out port capacity, thanks to the massive COVID-driven shift in U.S. consumer demand from experiences to stuff, with much of the stuff coming from maxed-out Asian factories and delivered on maxed-out ships through maxed-out West Coast ports. The number of vessels waiting at anchor offshore from Los Angeles’ terminals, for example, was near zero daily on average before 2020 but jumped to an average of 32 in November 2021 with 53 vessels inbound as of January 27th.

The newly enacted bipartisan infrastructure law includes $550 billion in new investments in surface transportation, port and rail modernization, and universal broadband expansion, which could address some of these capacity shortfalls.

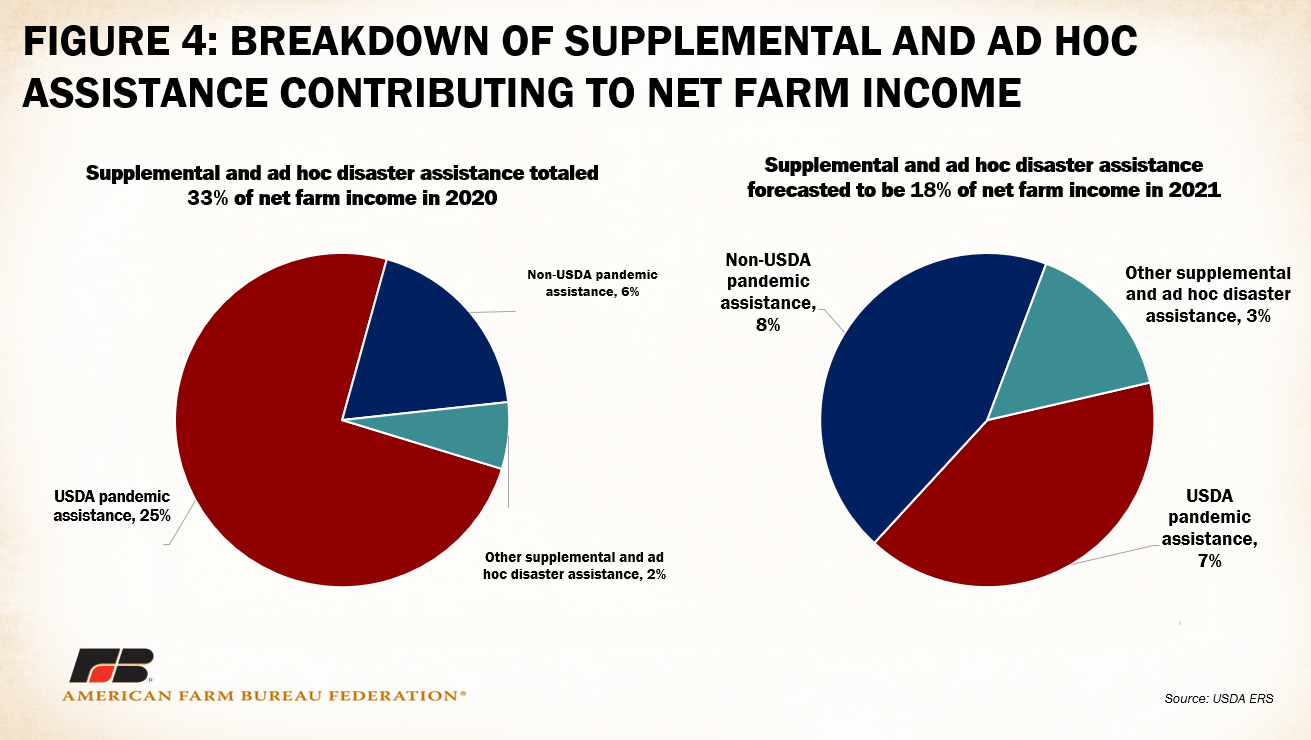

Natural disasters have been frequent and costly in recent years, from drought to wildfires to tornadoes, hurricanes and freezes. Disasters like these and the pandemic have fallen outside of the scope of traditional risk management programs, which are designed to provide targeted risk support under more “normal” conditions and drive popular and political demand for ad hoc disaster assistance programs like the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program + (WHIP+). Ad hoc disaster assistance payments have gone from 1% or 2% of net farm income through 2019 to 48% in 2020 and 24% forecasted in 2021 – primarily linked to pandemic-related programs. This will force a conversation about how the 2023 farm bill can encourage good risk management without leaving farmers and ranchers at the mercy of Mother Nature in a post-pandemic world.

Private climate markets, like carbon sequestration and ecosystem services credit markets, provide new challenges and opportunities for farmers in 2022 to address climate emissions. Standard definitions for carbon and ecosystem service credits remain undetermined. USDA’s Climate-Smart Agriculture and Forestry Partnership Initiative was announced in September but it will take time to define the farming and forestry practices and outcomes that USDA values and to begin supporting pilot projects that could expand opportunities for climate-smart practices on working lands; these decisions will provide critical context for the conservation provisions of the 2023 farm bill.

Strong export purchases at the end of 2020 drove much of the increase in crop prices into and throughout 2021, which many farmers were able to take advantage of. However, drought-related yield dips in many parts of the country, particularly for wheat, lowered some potential 2021 revenue. Despite weather and disaster impacts, many U.S. farmers are aiming to plant just as much corn, soybeans and wheat in 2022 compared to 2021, which was a record planting year, and a record year in soybean production. Early analysts’ expectations peg corn planted acres at 91.5 million acres, down about 2% compared to 2021, while soybean planted acres are estimated to reach 88.8 million acres, up 1.8% from 2021. Combined, corn and soybean acres would reach 180.3 million acres, which would be down slightly from the combined 180.6 million acres in 2021.

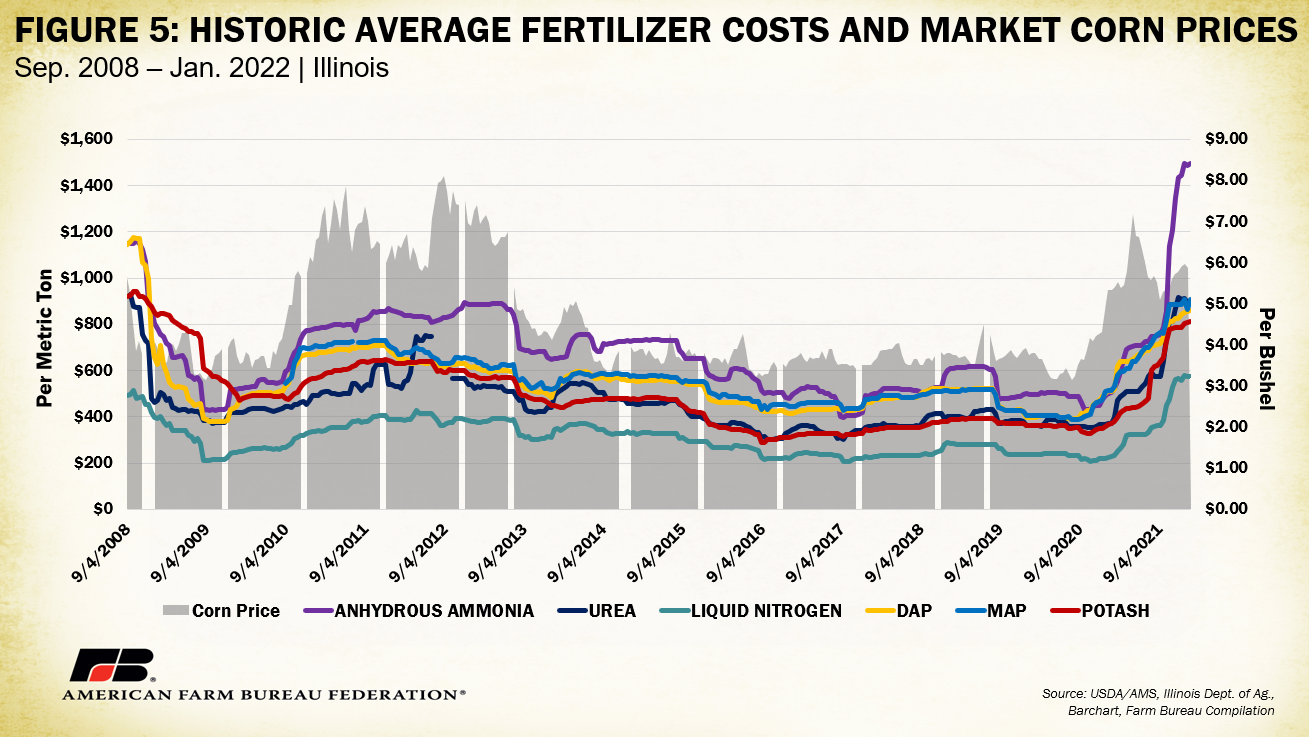

What factors may change those early projections? Rising input costs. High fertilizer prices, increasing more than 300% in some areas, and increased prices of other inputs -- like crop protection chemicals and land values, which increased 7% in 2021 compared to 2020 -- are tightening what could have been above breakeven profit margins. Figure 5 displays the historic average cost for six common fertilizer products with the market corn price for comparison. Note the variation in fertilizer prices does not always parallel changes in corn prices especially in the past six months. Looking into 2022, grain prices are expected to begin to pull back from their highs as global supply catches up to surging demand, but they are likely to remain above prices received before 2021.

After hitting its highest peak in over 20 years, the national dairy milking herd has dropped under 2017 and 2020 levels and with the drop comes a dampening in total and per cow milk production. Cold storage butter stocks are down 27% from 2020 fueled by high demand pushing Class IV futures prices upward. Continued tightening of milk supply bodes well for overall prices – though the knee-jerk reaction to add cows during signals of higher prices could counteract short-run supply trends.

Red meat supplies also remain below 2020 levels (by 6%). Low producer-received cattle prices sustained by a COVID-induced era of higher carcass weights and high supply are expected to wane as lighter weight animals head to market. Though feedlot placements were up 6% in December 2021 over December 2020, this is likely a result of a last-ditch option to get feeders to market given abysmal winter forage conditions and high hay prices. Sustained domestic and export demand for livestock and poultry products underpins a likely climb in producer-received prices into 2022.

In the end, the net market return for commodities across the board may exceed that of 2021, but without the massive pandemic-linked government payments of the last two years, net farm income will likely be down in 2022.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL