From Field to Kickoff: Where Super Bowl Foods Begin

Daniel Munch

Economist

Faith Parum, Ph.D.

Economist

Key Takeaways:

- Super Bowl abundance reflects the scale of U.S. agriculture. From chicken wings and cheese to chips, pizza and guacamole, farmers and ranchers from the 50 states and Puerto Rico supply the ingredients for one of the largest single-day food events of the year.

- Strong consumer demand does not guarantee strong farm margins. Across livestock, field crops and specialty crops, rising costs for labor, energy, inputs and financing have outpaced prices paid to farmers, leaving many producers facing tight or negative margins even as grocery shelves remain full.

- Super Bowl demand highlights how production constraints shape food sourcing. Exports help support farm prices for commodities like dairy, corn and wheat, while the spike in Super Bowl demand for foods like salsa and guacamole exposes the cost, seasonal, labor and regulatory pressures that limit U.S. tomato and avocado production and increase reliance on imports during peak consumption periods.

Americans will once again come together this Super Bowl Sunday, not just to cheer on their teams, but to enjoy classic game day foods. From buffalo wings and pizza to chips, queso, guacamole and salsa, farmers and ranchers across the country supply the ingredients that end up on millions of watch party tables.

For consumers, the Super Bowl represents the abundance of the U.S. food system. For farmers, it highlights the scale and coordination required to supply a single day of peak food demand, even as many farmers face rising costs, tight margins and growing uncertainty. Here’s a closer look at where some Super Bowl favorites come from and the challenges facing the farmers behind them.

From the Farm to the Watch Party

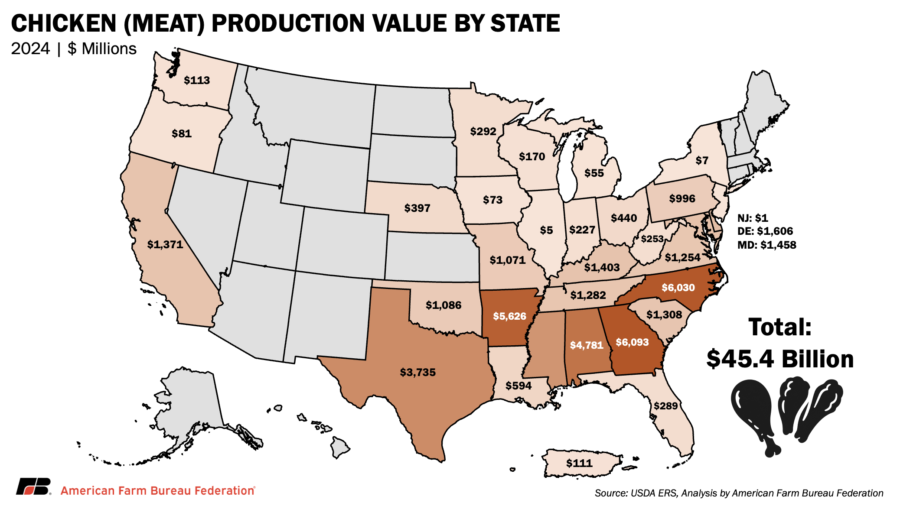

Chicken Wings

Few foods are more strongly associated with the Super Bowl than chicken wings. Americans are expected to eat well over a billion wings during Super Bowl weekend, supplied by poultry farmers concentrated across the Southeast and parts of the Midwest. States including Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas and North Carolina consistently rank among the nation’s top chicken-producing states. In 2024, farm-level poultry receipts totaled about $45.4 billion, making poultry one of the most valuable segments of U.S. agriculture.

While demand for wings remains strong, poultry growers operate in a highly consolidated, contract‑based system. Most farmers do not own the birds they raise and receive a set payment for growing them, limiting their ability to benefit when wholesale or retail prices rise. At the same time, growers typically finance and own their own poultry houses, often investing $1 million or more in specialized buildings and equipment, while also shouldering ongoing costs for energy, labor, biosecurity and disease management. Even on one of the biggest food consumption days of the year, strong consumer demand does not necessarily translate into stronger margins at the farm level.

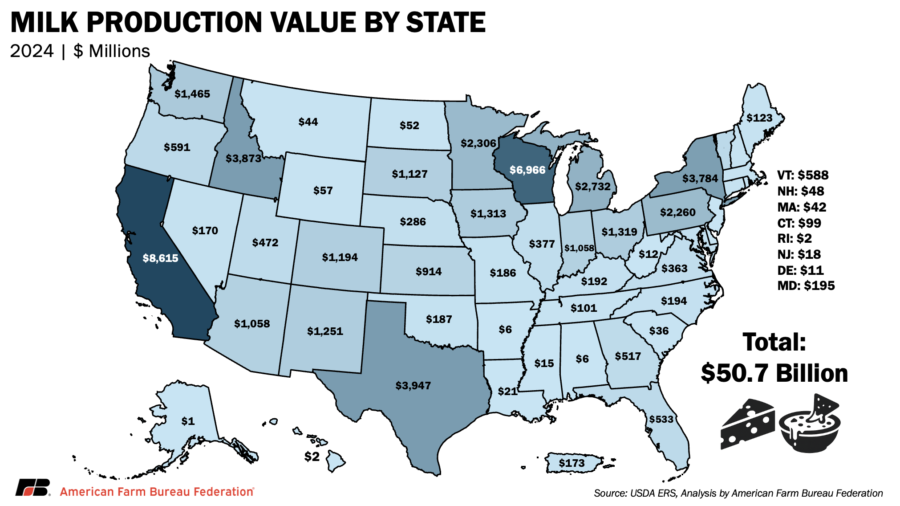

Cheddar Cheese & Queso (Milk)

Cheese, from mozzarella for pizza to queso dip and cheddar slices, is a quiet workhorse of Super Bowl spreads. All of it starts with milk, produced by dairy farmers across the country, with California, Wisconsin, Idaho, Texas and New York leading the way.

U.S. milk production is currently at record levels, helping keep cheese plentiful and affordable for consumers. But those volumes can be misleading. Much of today’s production reflects farmers keeping cows in the herd longer and breeding more cows for beef calves to help offset low milk prices, rather than expanding herds for milk production over the long term.

That dynamic has contributed to lower milk prices at the farm level, even as it has made U.S. dairy products highly competitive abroad and supported strong export volumes. For farmers, elevated feed additive, labor, fuel and interest costs mean lower prices translate directly into tighter margins, leaving many dairy operations under financial pressure even as cheese remains a Super Bowl staple. That pressure has reshaped the industry over time: as of 2024, the U.S. had roughly 24,800 dairy farms, down more than 60% from over 64,000 operations in 2005.

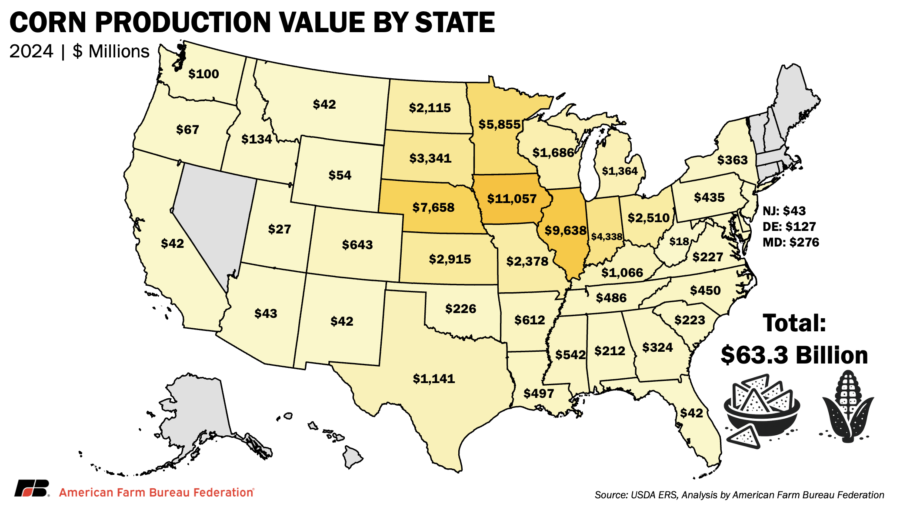

Corn

Corn tortilla chips and other corn-based snacks start with field (dent) corn — the most widely planted crop in the United States. Each year, farmers plant roughly 90 million acres of corn, with production concentrated in the Midwest, where states like Iowa, Illinois and Nebraska consistently rank among the top producers.

Corn’s role on Super Bowl Sunday reflects just one part of a much larger picture. About 40% of U.S. corn is used for livestock feed, supporting meat, dairy and poultry production. Roughly 33% is used for ethanol that helps Americans get to their Super Bowl watch party. On average, about 18% of this year’s U.S. corn production will be exported, connecting American corn farmers to global markets. The remaining corn is used for food and seed.

Only a small share of corn ends up directly on snack tables as corn flour for chips, but that versatility is exactly what makes corn such a cornerstone of U.S. agriculture. However, despite strong consumer demand for corn-based foods, fuels and exports, corn farmers are projected to lose an average of $173 per acre in crop year 2026, as elevated production costs continue to outpace market prices. From 2023 to 2026, corn farmers are estimated to lose $49.8 billion before the farm safety net takes effect. Even after receiving assistance, corn farmers are still expected to operate at a loss. From fueling vehicles to feeding livestock — and, on Super Bowl Sunday, filling chip bowls — corn farmers remain central to supplying both food and fuel markets, even as tight margins persist.

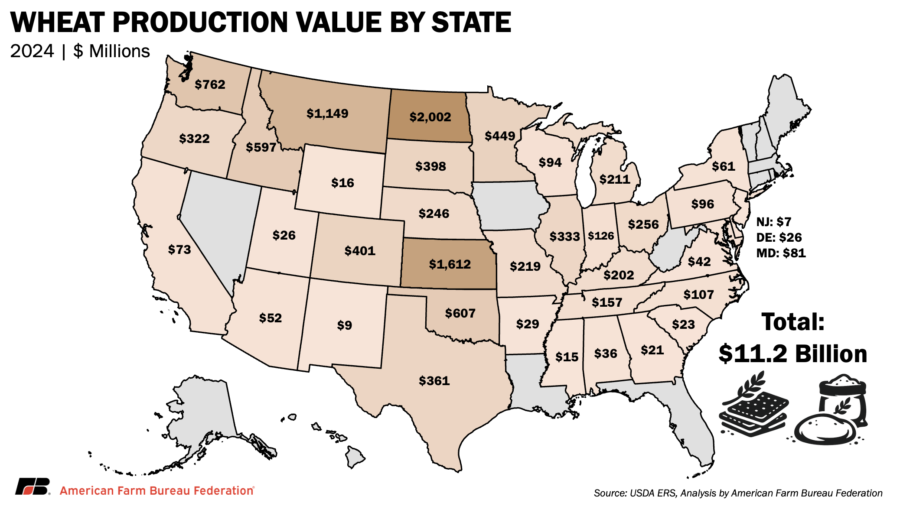

Wheat

Pizza crusts, crackers and other baked Super Bowl favorites all start with wheat — one of the most widely grown crops in the United States. Wheat is produced across much of the country, with North Dakota, Kansas and Montana among the top wheat-producing states, each specializing in different types suited for specific food uses.

Wheat plays a uniquely global role in U.S. agriculture. The United States exports roughly 45% of its wheat production on average, making foreign demand a critical driver of farm prices. The remaining wheat is used domestically, mostly for food products like bread, pizza crusts, crackers and pasta.

Hard red winter wheat — commonly grown in the central and southern Plains — is especially well suited for pizza dough due to its protein content and baking qualities. While wheat is a staple ingredient for many Super Bowl foods, producers continue to face financial pressure. Wheat farmers are projected to lose an average of $136 per acre in crop year 2026, as market prices remain below elevated production costs. From 2023 to 2026, wheat farmers are estimated to lose $20 billion before the farm safety net takes effect. Like other producers, even after assistance, wheat farmers are still expected to operate at a loss.

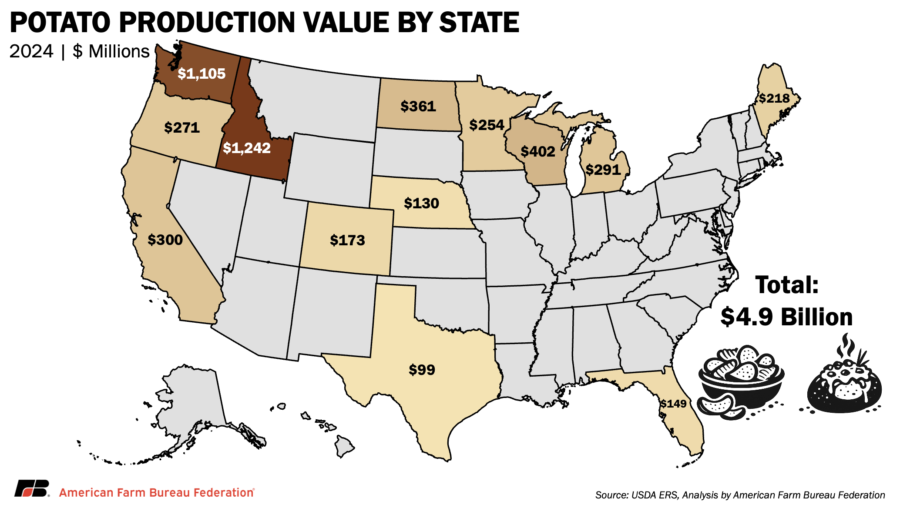

Potatoes

Potato chips, fries and baked potatoes are Super Bowl staples, supported by potato farmers concentrated in top states including Idaho, Washington, Wisconsin and North Dakota. Potatoes are among the most economically significant specialty crops in the United States, supplying nearly $5 billion in fresh and processed markets tied closely to snack food demand.

Behind that demand, many potato growers face rising costs for labor, energy, storage and other inputs that have outpaced what the market is paying. While some potatoes are sold under contracts that offer more predictable prices, growers with uncontracted potatoes have been especially exposed to price swings. Recent estimates suggest full production costs average around $12 per hundredweight, while market prices for uncontracted potatoes have often fallen short.

As a result, the potato sector is estimated to face roughly $700 million in losses, about $800 per acre, even as consumer demand for potato products remains strong. It’s a clear example of how popular foods can fill Super Bowl tables while farmers struggle to cover rising costs.

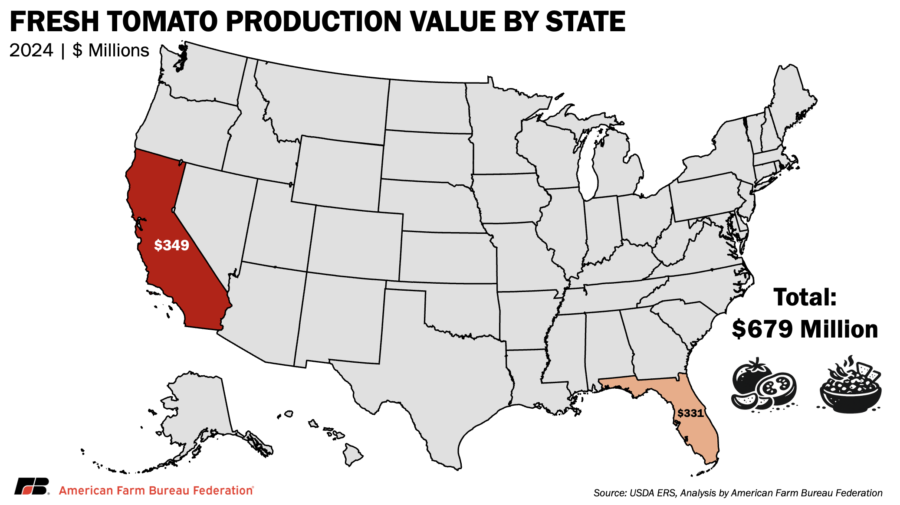

Tomatoes

Tomatoes are a key ingredient in salsa, pizza sauce and condiments that show up on Super Bowl tables nationwide. U.S. tomato production is concentrated primarily in California and Florida, though imports, especially from Mexico, now account for about 70% of tomatoes consumed in the United States.

For domestic growers, strong consumer demand has not translated into strong farm margins. In Florida, for example, tomato producers face production costs near $37,000 per hectare (roughly $15,000 per acre) but earn only about $33,400 in revenue, resulting in an implied loss of roughly $3,600 per hectare ($1,460 per acre). Labor alone accounts for 30%–40% of total production costs, and growers typically capture only about one-third of the retail tomato price. Rising labor expenses, regulatory compliance costs and competition from lower-cost imports continue to pressure U.S. producers, even as tomato-based foods remain a Super Bowl staple.

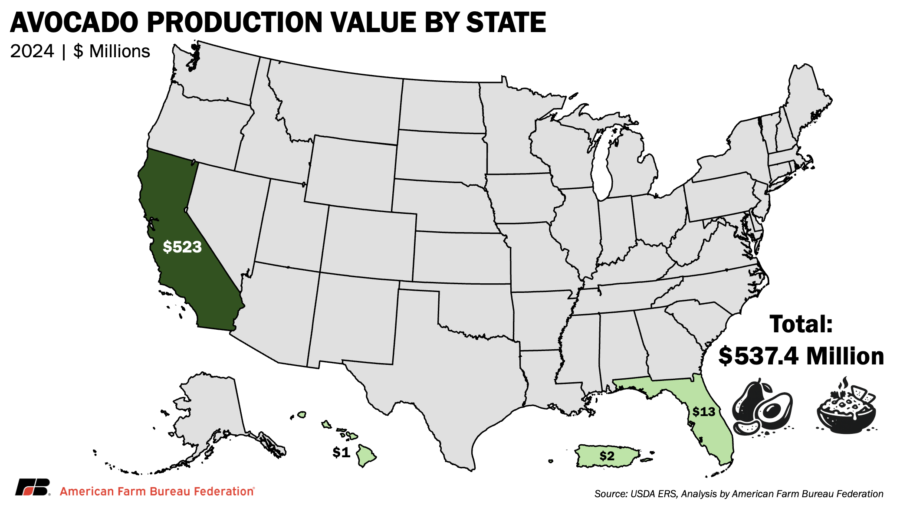

Avocadoes

Guacamole is a Super Bowl staple, driving one of the highest avocado consumption weeks of the year. While about $537 million of avocados are grown on over 5,500 farms domestically, primarily in California, with smaller volumes in Florida, Puerto Rico and Hawaii, U.S. production supplies only about 8% of domestic demand.

Unlike annual crops, avocados are a long-term, capital-intensive investment that can take years to reach full production. Geographic limitations, rising land and labor costs, and exposure to weather and disease add risk for growers, while specialty crop producers often have fewer risk management tools to offset losses. These factors make rapid domestic expansion difficult, even as demand continues to grow.

As a result, imports, largely from Mexico, help fill seasonal gaps and ensure consistent availability during high-demand periods like the Super Bowl. For U.S. growers, the challenge is not demand, but the structural and cost barriers that limit expansion at home.

Conclusion

Super Bowl Sunday offers a snapshot of the strength and reach of U.S. agriculture — a food system capable of delivering abundance, variety and affordability at an enormous scale. From wings and cheese to chips, salsa and guacamole, farmers and ranchers across the country supply the raw ingredients behind one of the biggest food consumption days of the year.

But beneath that abundance is a more fragile reality. Across commodities, many farmers face rising labor, energy, input and financing costs that market prices do not keep pace with. Strong consumer demand and full grocery shelves do not automatically translate into financial stability at the farm level. In many cases, the opposite is true: popular foods mask tight margins and structural pressures across U.S. agriculture.

As fans gather around their TVs this Super Bowl Sunday, it’s worth remembering that every bite reflects far more than what’s on the plate. It reflects a highly coordinated agricultural system and the farmers and ranchers working every day to keep it running, even as economic pressures continue to mount well beyond game day.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL