Farm Labor Wage Changes Coming to H-2A

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

The Department of Labor’s (DOL) new interim final rule (IFR) for H-2A guestworker Adverse Effect Wage Rates (AEWRs) makes significant changes to the wage calculation for farm laborers nationwide. Eagerly awaited by H-2A employers after the recent cancellation of the Farm Labor Survey (FLS) and litigation challenging other DOL rules, the IFR went into effect as soon as it was posted to the Federal Register on Oct. 2.

Utilizing data from Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS), H-2A employers will now pay wages based on tiers of job experience requirements and receive adjustments to offset the nonwage costs of the H-2A program, lowering employment costs for nearly all H-2A workers. However, the rule leaves some unanswered questions about how employers will implement the changes across the country.

Setting New Farm Labor Wages

OEWS wages are not a new factor in the H-2A program. A 2023 wage rule disaggregated wages, eliminating one Adverse Effect Wage Rate for all H-2A workers and instead requiring distinct wages for all Standard Occupation Classification (SOC) codes for job duties beyond what DOL considered farmwork, like driving a truck. However, a federal district court in Louisiana struck down that rule in its entirety nationwide on Aug. 25. These developments preceded DOL’s decision to make the OEWS the sole source of wage data in the H-2A program.

Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ OEWS is a randomized survey of employers compiled from state unemployment insurance (UI) databases from over a million nonfarm establishments. Yearly estimates posted each May contain a three-year average of the prior years for wages in each category. Overall, the OEWS has a response rate of 65%, similar to historical responses to the FLS, but the OEWS does not survey farm establishments. Employers who are categorized as support activities for crop production and support activities for animal production – also known as farm labor contractors (FLC) – are included in the possible survey pool if they file UI in their state. This skews OEWS accuracy for areas lacking a heavy FLC presence or in states without agricultural UI requirements. The IFR commits to working with USDA to add direct farm employers to the survey pool, but the business structure of most family farms will likely be major hurdles for incorporating farms into the program. Many farms lack dedicated business administrators, are exempt from state UI programs and differ in business data management from large companies. These factors, as well as farmer survey fatigue, will require a significantly different approach to include direct farm employers in OEWS data samples.

OEWS wages are published for over 800 occupations, including dividing the available data into percentiles and averages for hourly or annual earnings at the county, state and national levels. This will allow more granular AEWR calculations than were available under the FLS. However, the OEWS continues to show inconsistency in year-to-year wage changes. Average crop farmworker wages from 2023 to 2024 ranged widely from a 14% decrease in Utah to a 17% increase in Maine. National crop farmworker wages in the OEWS have also increased nearly 26% in the past five years, reflecting the trends of farm wages increasing much faster than nonfarm employment in recent years. This is likely partially due to H-2A workers, and thus previous AEWRs, being present in the agricultural wages, similar to the FLS, as FLCs will have guestworkers in their employment when completing the survey. Recent studies have also found that rising AEWRs have also likely driven up domestic farm wages as the presence, and awareness, of H-2A workers and their wages increases in farming communities.

One critical improvement the OEWS dataset makes is getting closer to base hourly wages. The survey does not include information on non-production-based wages or overtime pay, unlike the gross wages included in the FLS. This will especially benefit states without overtime laws that were previously grouped in regions with states that did have agricultural overtime laws. Under FLS AEWRs, overtime inclusion led to increased wages across broad regions.

The Wages

Similar to the output of the FLS, DOL will post standard farmworker AEWRs as a combined field and livestock worker wage covering the most common agricultural SOCs. The combined field and livestock worker wage under this IFR will include Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery and Greenhouse (45-2092); Farmworkers, Farm, Ranch and Aquacultural Animals (45-2093); Agricultural Equipment Operators (45-2091); Packers and Packagers, Hand (53-7064); Graders and Sorters, Agricultural Products (45-2041) but remove Agricultural Workers, All Other (45-2099). As this wage is not directly reported by the OEWS, it is calculated as the weighted average of the appropriate percentile wage per experience level for each of the five SOC codes in each state. The national average SOC code wage will be used if a state level estimate is not available.

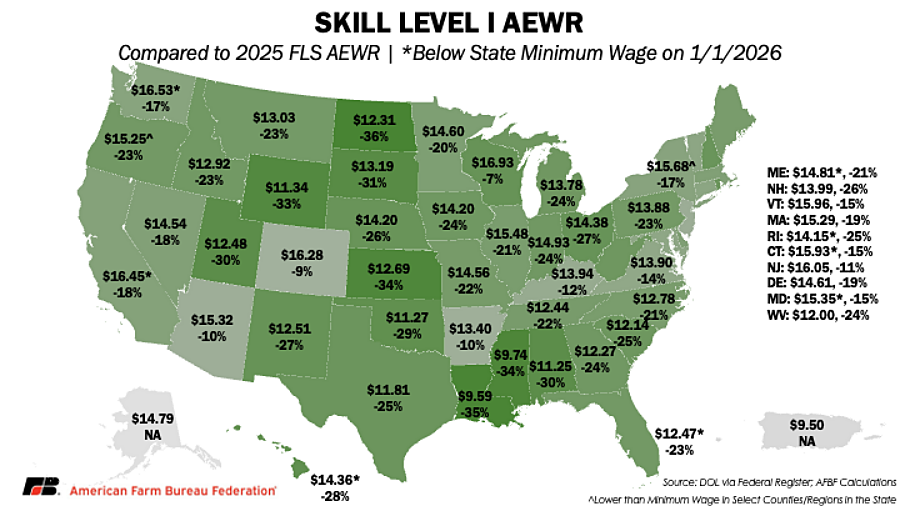

Under the new rule, H-2A job orders will be certified at two different experience levels corresponding to different combined field and livestock worker AEWRs. DOL expects most H-2A jobs to classify as a Skill Level I, meaning they need no prior experience in the duties and limited training on the job. DOL estimates that entry-level workers make up one-third of agricultural workers in each SOC code, so the Skill Level I wages will be based on the weighted average of the 17th percentile – the median point of the lower third of workers – of OEWS wages.

This adjustment results in nearly immediate savings for every state as any job orders certified after the introduction of this rule will be certified with the new wage rates. However, because H-2A employers must pay the highest of the AEWR, the state or federal minimum wage, the prevailing wage or the collective bargaining wage, many states will now face state minimum wages above the AEWR. This will limit cost savings to farmers in those states.

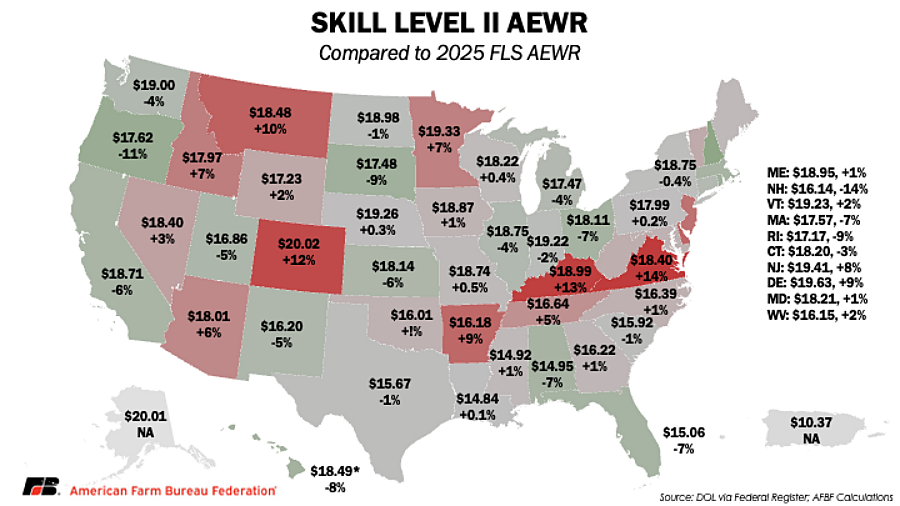

Skill Level II jobs require prior experience, certifications or technical knowledge that allow them to work with less supervision, such as workers responsible for the first pick of an apple orchard determining if fruit is ripe. These wages will be a combined field and livestock worker wage of the average hourly wages of the “big five” SOC codes statewide. When examining just the new AEWR for Skill Level II employees, an OEWS combined field and livestock worker wage would increase wages for Skill Level II jobs in 26 states.

Fortunately, the IFR recognizes the substantial nonwage costs to farmer employers for H-2A workers and has taken steps to mitigate some of that burden as well.

Adverse Compensation Adjustments

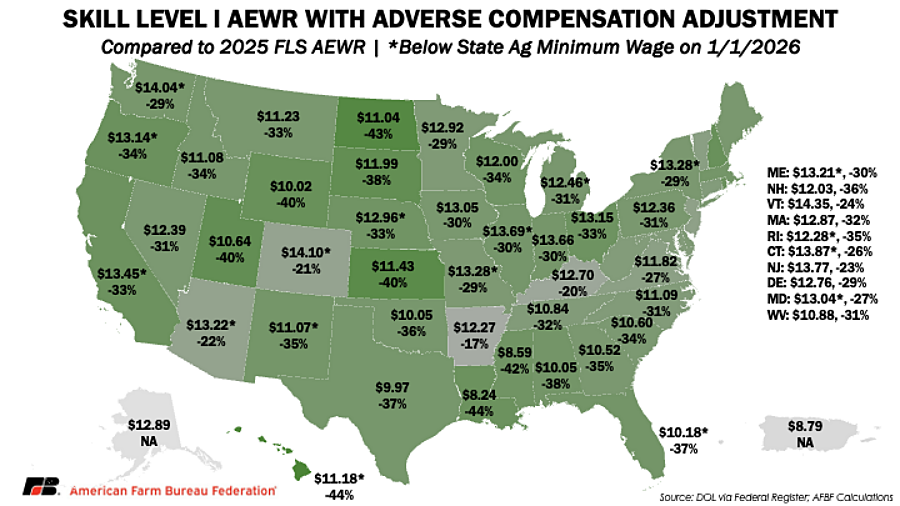

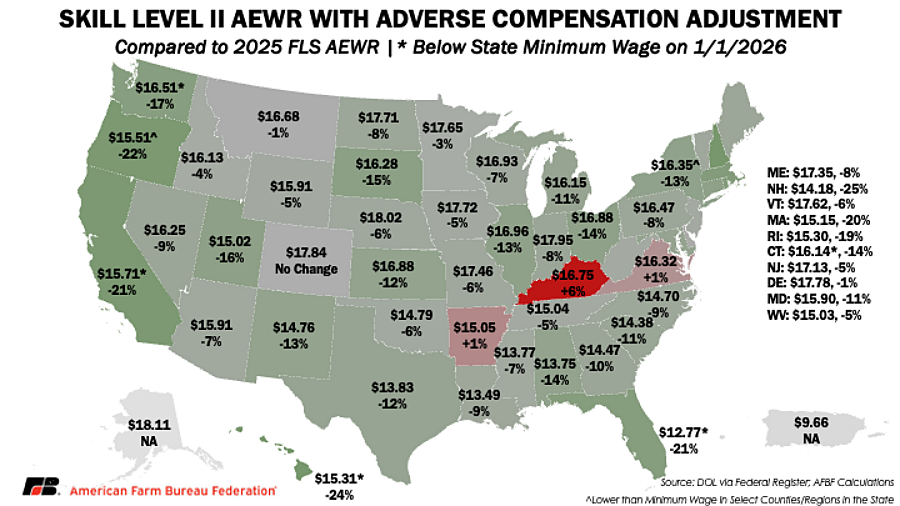

Since domestic farmworkers often pay for their own housing, the H-2A program requirement that farmers provide free housing to their H-2A workers is considered an adverse effect on domestic employment. Domestic workers who “are reasonably able to return to their permanent places of residence at the end of each workday” do not have to be provided free employer housing if they are employed in corresponding roles to H-2A workers. As such, H-2A workers generally retain more of their income compared to domestic workers who must spend additional income on living expenses, even if domestic workers earn the same hourly wage.

To account for this nonwage compensation afforded to H-2A guestworkers above domestic workers, the IFR establishes a state-level compensation deduction for H-2A workers. These deductions are based off the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) 50th percentile rents for a four-bedroom housing unit, including utilities except telephone, television or internet. DOL categorizes these as “state average Fair Market Rents (FMRs),” but HUD’s website discloses that these are not FMRs as they are skewed by outlier rental rates in some areas.

The average occupancy of H-2A housing units was seven to eight workers for labor certifications processed from fiscal year 2020 to 2024. As such, the FMR is divided among eight individuals who are assumed to work 40 hours per week to come up with an hourly equivalent of fair housing rates. To ensure H-2A wages are not depressed beyond appropriate income shares for housing, the adverse compensation adjustment may not exceed 30% of the AEWR.

The adverse compensation adjustments range from 71 cents and $1.20 per hour in Puerto Rico and West Virginia, respectively, to $3 in California and $3.18 in Hawaii. No compensation adjustments currently surpass the 30% cap. These adjustments balance wage costs so that most states will see lower hourly costs than under the FLS, but three state still have a higher per-hour wage for Skill Level II roles than under previous rules: Arkansas, Kentucky and Virginia.

The adverse compensation adjustment would push the AEWR below the state minimum wage for eight states: Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska and New Mexico. This puts domestic and H-2A workers back at the same wage, despite the compensation disparities DOL says exists between the groups. Even at the higher Skill Level II wages, seven states have AEWRs below the state minimum wage with the compensation adjustment (California, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, New York, Oregon and Washington), eradicating the efforts to allow higher compensation for higher skilled employees and level the payroll costs, and living expenses, of H-2A and domestic workers.

Employers may only deduct this adverse compensation adjustment from H-2A worker wages, not corresponding domestic workers, even if domestic workers live in employer-provided housing. All considered, domestic workers will receive the state minimum wage instead of the AEWR by Jan. 1, 2026, in eight states (California, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Rhode Island and Washington), and in two additional states, Oregon and New York, where it will apply only in more urban areas.

Disaggregated Wages Remain

Despite the recent litigation outcome on the 2023 disaggregation rule, the IFR does not eradicate the potential for wage determinations in additional SOCs. Instead, it implements a primary job duties test. If a worker performs duties reasonably expected to be performed under the five farmworker SOCs – which will be determined by standards in the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) system – for over 50% of their workdays, they will be assigned the combined field and livestock worker wage. However, if they perform duties outside of these expectations for a majority of their contracted time, DOL and state workforce agencies (SWA) may still certify a job order with wages based on nonfarm jobs.

Use of O*NET should allow greater flexibility in job duties classified under the combined field and livestock worker wage. The system contains greater variability in tasks considered reasonable agricultural work, including those tasks that may be less regularly performed that were previously considered “nonagricultural”, like driving a van of farmworkers. The rule commits that SWA and DOL will attempt to assign one agricultural SOC code to job orders whenever possible, using the extended job duties included in O*NET.

Impact to Employers

DOL estimates that the new rule will save farmers an average of $2.4 billion per year over the next 10 years, allowing farmers to reinvest in their farm, including in new equipment, technologies and employee housing. However, when accounting for state minimum wages that will now be effective in the H-2A program and corresponding employees who will see wage increases, this benefit is likely overstated.

Farmers and ranchers have long called for reform to the H-2A program, particularly the wage setting methods and nonwage costs of the program, and pieces of this rule begin to recognize and take steps to modernize the AEWR system. While any existing job contracts must continue paying the wages on their job orders — except in the few states where this rule increases wages — any H-2A certification applications submitted on or after Oct. 2 will immediately see relief for most workers. As growers nationwide grapple with rising production costs, low prices and trade disparities – especially in the fruit and vegetable industries – access to a stable, affordable workforce is critical to keeping affordable food on American families’ tables.