SDRP Shallow-loss Formula Understates Harvest-Time Losses

TOPICS

Disaster Relief

Daniel Munch

Economist

Key Takeaways

- The Supplemental Disaster Relief Program (SDRP) Stage 2 was designed to fill gaps left by Stage 1, including assistance for “shallow-loss” farms that carried coverage but did not trigger an indemnity.

- USDA’s Stage 2 shallow-loss math values production using the spring (projected) price, even when the harvest price is lower, a choice that can reduce or eliminate recognized loss in falling-price years.

- Stage 1 was more aligned with harvest-season economics, so many growers expected Stage 2 would work similarly.

- The spring-price approach is easier to defend on budget scoring, but it can miss real-world revenue stress for farms whose yield loss was modest, but whose cash price environment deteriorated by harvest.

As farmers begin to evaluate potential payments under the Supplemental Disaster Relief Program (SDRP) Stage 2, a common concern has emerged across farm country: in many cases, the program’s calculation of shallow-losses does not capture the change in revenue farmers experienced at harvest due to lower crop prices.

The issue stems from how Stage 2 values production, i.e., crop revenue, when determining whether a “shallow” or uncovered loss exists. USDA’s formula relies on spring crop insurance prices, even in years when market prices declined between planting and harvest. For example, in 2023, Stage 2 values corn production using a spring projected price of $5.91 per bushel, even though the harvest price fell to $4.88 a difference of $1.03 per bushel, or roughly 17%. For farmers whose yields or revenues were reduced by drought, flooding or other qualifying natural disasters, but not enough to trigger an insurance indemnity, this approach can shrink or eliminate the loss USDA recognizes for the purposes of administering the program.

In practical terms, that means that program payments for some farmers with clear disaster-related losses are either significantly smaller than expected, or completely eliminated, despite facing meaningful revenue declines when the crop was harvested. Understanding why this happens requires stepping back to look at how SDRP Stage 2 is structured and where shallow loss fits within the broader program.

Background: How SDRP Stage 2 Is Structured

USDA’s Supplemental Disaster Relief Program was created to deliver one-time assistance for agricultural losses tied to natural disasters in 2023 and 2024. To accomplish that, USDA divided SDRP into two stages, reflecting the different ways losses show up in the existing farm risk management tools.

Stage 1 focused on losses already captured in existing programs. It provided supplemental payments to producers who received a crop insurance or Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) indemnity for a qualifying disaster loss. Stage 1 requirements and calculations were described in an earlier analysis: USDA Launches 2023-2024 Crop Loss Disaster Assistance.

Stage 2 is broader and is intended to address the remaining gaps. It covers several categories of loss not fully addressed in Stage 1, including uninsured crops, certain quality and value losses, and situations where producers experienced revenue declines but did not receive an insurance indemnity or NAP payment. Stage 2 requirements and calculations were broadly described in an earlier two-part analysis: Understanding USDA’s New Natural Disaster Relief: Part 1 which covers quality loss and shallow loss coverage and Part 2 which covers uninsured crops, value-loss crops, trees/bushes/vines, on-farm storage losses and milk losses.

Within Stage 2, shallow loss is just one category. Shallow-loss assistance applies to insured or NAP-covered producers whose yields or revenues declined but remained inside the deductible space or above the level needed to generate an indemnity. For example, a producer insured at an 80% coverage level who experienced a 19% decline in revenue would not receive a crop insurance payment, even though nearly one-fifth of the value of the crop was lost.

Falling Harvest Prices Set the Stage

The impact of USDA’s spring-price decision is most pronounced in years when prices decline between planting and harvest. That was the case for many major crops in both 2023 and 2024. Harvest prices for corn, soybeans and soft red winter (SRW) wheat were lower than their spring projected prices in both years, and cotton prices also declined between spring and harvest in 2024. The lone exception amongst these four crops was cotton in 2023, when the harvest price increased only marginally, by roughly one cent, relative to the spring price. In several instances, spring-to-harvest price declines exceeded 10% to 20%, meaning many producers ultimately marketed their crops into a significantly weaker price environment than the one that existed at planting.

For producers who suffered yield losses but did not trigger an insurance or NAP payment, these price declines compounded the financial hit. However, SDRP Stage 2’s shallow-loss calculation does not incorporate those harvest-time price movements. Instead, production is valued using the higher spring price, even when the crop was ultimately harvested at a time with much lower prices.

This dynamic is particularly important because shallow losses, by definition, sit near insurance and NAP trigger thresholds. When losses are within the deductible level, small changes in how production is valued can meaningfully alter whether a loss is recognized at all under the Stage 2 formula.

Price Choice Affects Insurance Plans Differently

Although SDRP Stage 2 applies across insured, NAP-covered and uninsured acres, the spring-versus-harvest price decision interacts differently with different types of coverage.

For yield-based coverage, such as Actual Production History (APH)-style crop insurance or NAP, indemnities are triggered strictly by production falling below a guaranteed yield; there is no harvest price option that adjusts coverage or triggers. Market prices do not affect whether a payment is triggered. As a result, producers can experience substantial revenue losses driven by a combination of yield damage and lower harvest prices while still receiving no insurance or NAP payment. When SDRP Stage 2 then values production using the higher spring price, it can further compress the calculated loss, reducing or eliminating shallow-loss assistance.

For revenue-based coverage, the relationship is more nuanced. Revenue Protection (RP) policies incorporate prices into the guarantee, but in years when harvest prices are lower than spring prices, the guarantee remains tied to the higher spring value, and in years when the harvest price is above the spring price, the guarantee reflects the replacement value for crop losses. Producers with modest yield losses may still fall just above the revenue trigger and receive no indemnity. In those cases, SDRP Stage 2 again relies on spring prices to value production, which can understate the remaining revenue gap when harvest prices fell.

Across both plan types, using spring prices consistently makes production appear more valuable than it was at harvest, shrinking the gap SDRP Stage 2 is designed to fill.

What the Yield Examples Show

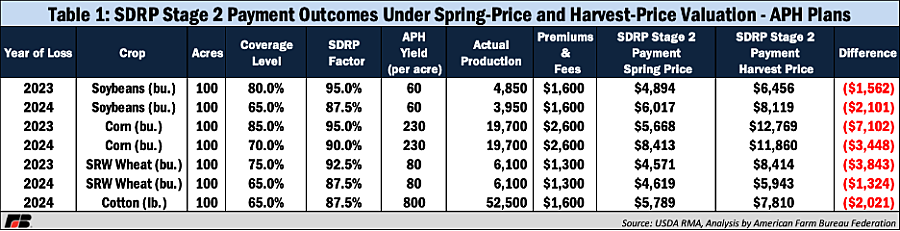

Table 1 summarizes how USDA’s spring-price valuation affects SDRP Stage 2 shallow-loss payments for hypothetical farmers insured under APH (yield-based) plans. In each example, the grower experienced a disaster-related production loss but did not trigger an underlying APH indemnity, placing the loss squarely within the shallow-loss category Stage 2 was designed to address. All examples assume a 100% price election and 0% quality loss. Premium values are illustrative and not tied to a specific policy or county.

Importantly, yield-based policies such as APH and NAP do not adjust indemnities based on harvest prices; payments are triggered solely by production falling below the guaranteed yield, using a fixed price election established before the season.

The core pattern is consistent across crops and years: when harvest prices are lower than spring projected prices, valuing production at the spring price materially reduces the loss USDA recognizes — and therefore the Stage 2 payment.

A 2024 soybean example illustrates this clearly. Consider a producer farming 100 acres of soybeans with an APH yield of 60 bushels per acre insured at a 65% coverage level. That coverage establishes an APH guarantee of 3,900 bushels. The producer harvested 3,950 bushels, remaining just above the insurance trigger and receiving no crop insurance indemnity, despite a meaningful yield loss of 20 bushels per acre or 34%.

Under USDA’s Stage 2 calculation, both expected and actual production are valued using the spring projected price of $11.55 per bushel. Valuing the harvested bushels at that price makes the crop appear more valuable on paper than it ultimately was at sale, when the harvest price had fallen to $10.03. Using the spring price, the producer’s Stage 2 payment totals $6,017 after applying SDRP factors, premiums and the 35% payment rate.

If the same harvested production were valued at the harvest price, the recognized shallow loss would be larger, resulting in an estimated $8,119 payment — more than $2,100 higher on a 100-acre unit. The difference reflects price choice alone; acreage, yield and coverage remain unchanged.

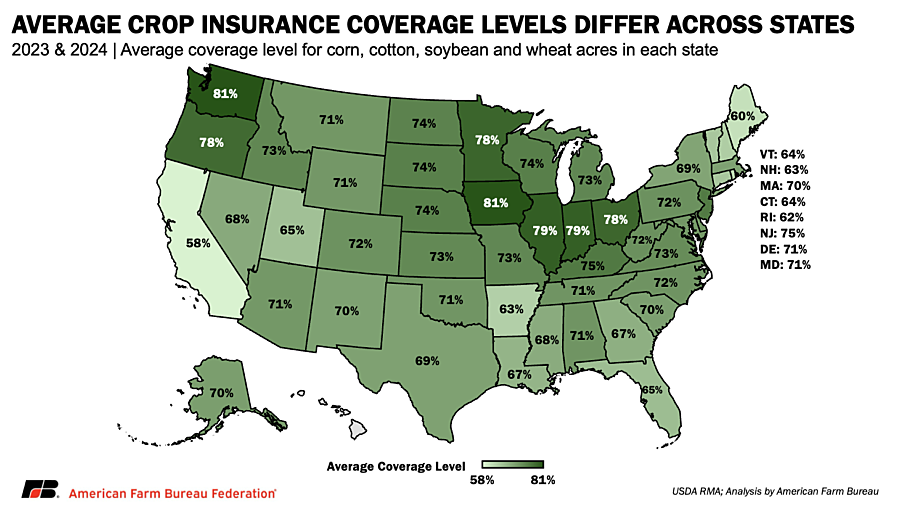

Notably, higher coverage levels do not insulate producers from the effect. Producers insured at 80% or 85% coverage still appear in the shallow-loss category when losses fall just above the trigger. In those cases, the spring-price valuation can sharply compress Stage 2 payments despite relatively high coverage, as illustrated by the 2023 corn (85%) and 2024 cotton (80%) examples. In regions where higher coverage is the norm, particularly across major Corn Belt states, a larger share of farmers are more likely to encounter the shallow-loss scenarios described, effectively disadvantaging producers who opted for higher-cost coverage.

What Revenue Protection Examples Show

The spring-price issue becomes even more pronounced for producers insured under RP plans, which are designed to protect against both yield and price risk. Under RP, guarantees are set using the spring projected price, but actual revenue is valued using the harvest price when prices fall. That structure allows crop insurance to recognize revenue losses driven by weaker markets at harvest.

SDRP Stage 2 departs from that logic. While it uses RP data inputs, the shallow-loss calculation values production using the spring price only, ignoring harvest-price declines. In falling-price years, this can cause the Stage 2 trigger to sit above the RP claim trigger, leaving some producers with no remaining uncompensated loss for Stage 2 to cover.

Assume a producer farms 100 acres of corn insured under an 85% RP policy with an approved APH yield of 230 bushels per acre. In 2023, the spring projected price was $5.91 per bushel, while the harvest price fell to $4.88.

Under RP, the revenue guarantee is based on the spring price:

RP revenue guarantee = 23,000 bu × $5.91 × 85% ≈ $1,155.41 per acre (≈ $115,541 on 100 acres)

Suppose the producer’s harvested crop generated actual revenue of approximately $115,656 when valued at the harvest price. Because actual revenue finished just above the RP revenue guarantee, no crop insurance indemnity was triggered, leaving the producer with no Stage 1 payment.

Despite avoiding an insurance payout, the producer still faced meaningful revenue stress relative to planting-time expectations, placing the unit in the category SDRP Stage 2 shallow-loss assistance is intended to address.

Under SDRP Stage 2, however, harvested production is valued using the spring price, not the harvest price. Applying the spring price to the same production results in a calculated production value of roughly $140,000.

That spring-price valuation pushes the calculated value of production above the program’s benchmark, leaving no uncompensated loss under the Stage 2 formula and resulting in no shallow-loss payment.

That spring-price valuation makes the harvested crop appear more valuable than the RP guarantee itself, effectively erasing the “revenue loss that earlier shallow-loss disaster programs were more likely to recognize. Once SDRP factors are applied, the formula shows no uncompensated loss eligible for payment, resulting in a $0 Stage 2 shallow-loss payment.

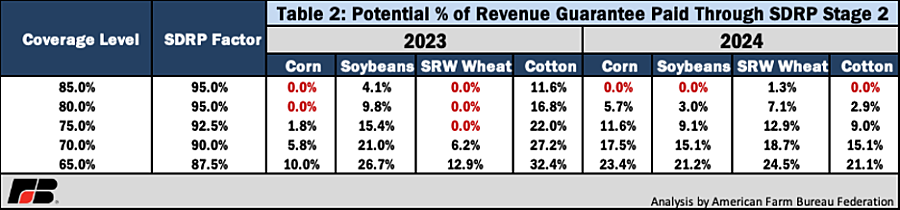

The example above is not unique. Table 2 shows how much of a farmer’s insured revenue could ever be paid through SDRP Stage 2 once crop insurance is taken into account, given the program’s use of spring prices. These percentages are derived by comparing the Stage 2 payment trigger to the underlying RP revenue guarantee using spring projected prices, illustrating how much “room” remains for a shallow-loss payment after insurance is accounted for.

At higher coverage levels, particularly 80% and 85% RP, Stage 2 offers little to no remaining payment capacity in many cases. For corn, soybeans and cotton in 2024, producers at 85% coverage show zero percent potential payment under Stage 2. In other words, once the spring-price valuation is applied, the Stage 2 trigger sits above the RP claim trigger, leaving no mathematical space for a shallow-loss payment regardless of yield loss, location or disaster type. Under a harvest-price valuation, those same losses would have generated a payment.

Conclusion

SDRP Stage 2 was designed to address a wide range of disaster-related losses not covered in Stage 1, including uninsured crops, quality and value losses, and shallow losses that fell just above insurance and NAP triggers. Within the shallow-loss portion of the program, however, USDA’s reliance on spring projected prices can understate real-world losses in years when prices decline between planting and harvest.

As the examples show, valuing production at spring prices can shrink or eliminate shallow-loss payments for farms that experienced meaningful yield and revenue declines, particularly when losses sit near trigger thresholds.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL